Introduction

In recent years, the concept of social determinants of health (SDOHs) has become increasingly recognized as a critical factor influencing the well-being of individuals, particularly children. SDOHs are defined by the World Health Organization as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.” These conditions encompass various domains such as economic stability, education, social and community context, health and healthcare access, and neighborhood environment. Recognizing the profound impact of SDOHs on health outcomes, especially during the formative years of childhood, there’s a growing emphasis on incorporating SDOH screening into pediatric primary care. Early identification of social risks can pave the way for timely interventions, acting as a primary prevention strategy against future health challenges and promoting lifelong well-being.

However, the integration of social determinants of health screening tools within pediatric primary care is not without its complexities and debates. Concerns have been raised about the ethical implications of screening without adequate resources to address identified needs, potentially leading to unmet expectations and anxieties for families. Conversely, proponents argue that even in resource-constrained settings, SDOH screening offers significant benefits. These include enhancing diagnostic accuracy, identifying children who require additional support, strengthening the patient-provider relationship, and generating crucial epidemiological data. Despite the acknowledged importance of addressing social needs, many healthcare professionals express feeling unprepared to tackle these issues within existing healthcare frameworks. Simultaneously, numerous care teams are actively working to identify and connect families with necessary social services. This ongoing discussion highlights a crucial gap in our understanding: the current state of SDOH screening science in pediatrics. What tools are available? How reliable and valid are they? And how effectively do screening results guide care and improve outcomes for children?

This article addresses these critical questions through a comprehensive review of the existing literature on social determinants of health screening tools used with children. While previous reports have provided overviews of SDOH screening tools in pediatric clinical settings, this review offers a systematic and in-depth analysis. Our aim is to catalog the diverse range of SDOH screening tools designed for children and youth, evaluate their psychometric properties—specifically their reliability and validity—and assess their practical application in detecting early risk indicators and informing tailored care strategies. By synthesizing the current evidence, this review seeks to provide valuable insights for healthcare professionals, researchers, and policymakers involved in pediatric primary care, ultimately contributing to the effective integration of SDOH considerations into routine child health management.

Methods

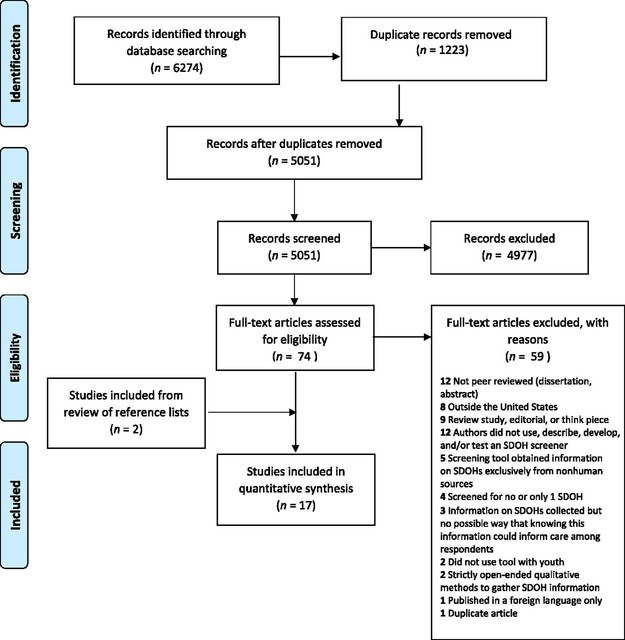

This systematic review meticulously examined the landscape of social determinants of health screening tools utilized for children and adolescents. Our methodology, guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines, involved a rigorous search across multiple research databases, a stringent screening process for study selection, and a detailed extraction of pertinent data from included studies.

Search Strategy

To capture a comprehensive range of relevant literature, we conducted electronic searches across five major databases: PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) via EBSCO, Embase via Elsevier, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Web of Science Core Collection. The search was limited to articles published in English, spanning from the inception of each database up to November 2018. Our search strategy focused on retrieving articles addressing three core concepts: (1) social determinants of health, (2) pediatric populations, and (3) screening administered by child service providers (such as clinicians, social workers, or educators) or within service provider settings (e.g., self-administered questionnaires in a pediatrician’s office). The detailed search strategies employed for each database are available in the Supplemental Information. All search results were compiled in EndNote, and duplicate entries were removed. The remaining references were then uploaded to Covidence systematic review software (https://www.covidence.org), a specialized online tool designed to streamline and track each stage of the review and abstraction process.

Study Selection Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this review were carefully defined to ensure the selection of studies directly relevant to our objective. We included studies that focused on tools screening children (or caregivers/informants on their behalf) for multiple SDOHs, aligned with the Healthy People 2020 definition of SDOHs. To maintain focus and relevance to the US healthcare context, we limited inclusion to studies conducted within the United States, published in peer-reviewed journals, and written in English. Studies were excluded if they: screened for only a single SDOH, did not involve screening of children (aged 0-25 years) or their caregivers/informants, were not published in English, were conducted outside the United States, or were non-peer-reviewed publications such as book chapters, reviews, letters, abstracts, or dissertations.

Data Extraction Process

Study selection and data extraction were conducted using Covidence, the online platform facilitating efficient management of the process. Title and abstract screening were performed independently and blindly by two reviewers for each study. Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. This independent, blind review process was also applied to full-text screening. Following both screening phases, lead investigators reviewed the included studies to confirm adherence to inclusion criteria. Any articles with uncertainties were discussed among lead investigators to reach consensus on inclusion status. Reference lists of included studies were also reviewed to identify any additional relevant studies.

Upon full-text review, a structured data extraction tool was developed within REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure web-based platform for building and managing databases and surveys. This tool was used to extract the following categories of information:

- Study Characteristics: Author and publication year, study type, setting, age range of screened children, sample size, percentage of female participants, race/ethnicity of participants, and study aims.

- Screening Tool Characteristics: Average completion time, screening setting, administration method, informant type (e.g., parent, caregiver), training requirements for screening professionals, language availability, suitability for low-literacy populations (defined as sixth-grade reading level or lower), and validation status.

- SDOH Domains Screened: Based on Healthy People 2020 domains (economic stability, education, health and health care, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context). An additional domain, “family context,” was included to capture aspects related to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) commonly assessed in these tools.

- Screening Follow-up Procedures: Whether screening results were discussed with respondents, referrals to community resources were offered or scheduled, and whether interventions were implemented.

Primary reviewers extracted data from assigned studies, and secondary reviewers verified the extracted data for accuracy. Discrepancies were resolved through team discussion and consensus.

Results

Study Selection

Our comprehensive electronic database search initially yielded 6,274 references, of which 1,223 were duplicates. After removing duplicates, 5,051 unique studies remained. Title and abstract screening eliminated 4,977 studies deemed irrelevant, leaving 74 articles for full-text review. Of these, 15 studies met the full inclusion criteria. Additionally, reviewing the reference lists of these 15 studies identified 2 more eligible studies, resulting in a final set of 17 studies for abstraction and analysis. The PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1 visually summarizes this study selection process.

FIGURE 1

FIGURE 1

Study Characteristics

Table 1 presents the key characteristics of the 17 studies included in our review, encompassing 11 unique SDOH screening tools. With the exception of one study conducted in home visiting programs, all studies were situated within medical settings, predominantly pediatric clinics. Among the 14 studies reporting the age range of screened individuals, the majority (8 studies) focused exclusively on screening during early childhood, specifically ages 0 to 5 years. The study samples were generally balanced in terms of biological sex. Race and ethnicity data, available for 13 studies, revealed that ten studies included predominantly non-white samples, reflecting the focus on diverse and often underserved populations in SDOH screening research.

TABLE 1. Study Characteristics

| Screening Tool | Author and Year | Study Type | Setting | Age Range, y | Sample Size | Female Sex, % | Race and Ethnicity (%) | Study Aim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEEK PSQ | Dubowitz et al 2007 | OC | Pediatric clinic serving an urban, low-income population | 0–5 | 216 | 44 | African American (92); white (3); multiracial (5) | Estimate the prevalence of parental depressive symptoms and evaluate a parental depression screen |

| Dubowitz et al 2009 | RCT | Pediatric clinic serving an urban, low-income population in Baltimore, Maryland | 0–5 | 308 | 46 | African American (93) | Evaluate the efficacy of the SEEK model in reducing child maltreatment | |

| Dubowitz et al 2012 | RCT | Pediatric practices serving suburban, middle-income populations | 0–5 | 595 | 50 | African American (4); white (86); Asian American (2); Hispanic (1); other (8) | Examine SEEK model effectiveness in reducing maltreatment in middle-income suburban populations | |

| Eismann et al 2018 | Observational only | Pediatric practice, family medicine practice, and FQHC serving various populations | 0–18 | 1057 | NR | NR | Assess SEEK model generalizability and identify integration barriers/facilitators | |

| iScreen | Gottlieb et al 2014 | RCT | Pediatric emergency department serving a low-income urban population in California | 0–18 | 538 | NR | NR | Compare adversity disclosure rates in face-to-face vs. electronic formats |

| Gottlieb et al 2016 | RCT | Primary care or urgent care departments in safety-net hospitals serving low-income populations in California | 0–18 | 1809 | 51 | African American (26); white (4); Asian American (5); Hispanic (57) | Evaluate social issues addressing impact on social needs and children’s health | |

| HealthBegins Upstream Risks Screening Tool | Hensley et al 2017 | Observational only | FQHC serving Southwestern Ohio and Northern Kentucky | NR | 114 | NR | NR | Explore systematic screening process for SDOH risks |

| FMI | McKelvey et al 2016 | Observational only | Home visiting programs serving at-risk families in the Southern United States | 0–5 | 1282 | 51 | African American (22); white (60); Hispanic (16); other (2) | Develop an assessment of children’s exposure to ACEs |

| ASK Tool | Selvaraj et al 2018 | Observational only | Pediatric primary care clinic serving an urban, low-income population in Chicago, Illinois | 0–18 | 2569 | 48 | African American (55); white (7); Asian American (5); Hispanic (21); other (12) | Determine toxic stress risk factors prevalence, screening impact on referrals, feasibility/acceptability |

| IHELP | Colvin et al 2016 | Observational only | Pediatric hospital in Kansas City, Missouri | NR | 347 | 46 | African American (22); white (55); Asian American (1); other (22) | Determine brief intervention effectiveness to improve social needs screening by residents |

| WE CARE survey instrument | Garg et al 2007 | RCT | Hospital-based pediatric clinic serving a low-income, urban population | 0–10 | 100 | NR | African American (96); white (1); Hispanic (3) | Evaluate feasibility/impact of intervention on managing family psychosocial topics |

| Garg et al 2015 | RCT | Community health centers serving an urban population in Boston, Massachusetts | 0–5 | 168 | NR | African American (44); white (24); Asian American (2); Hispanic (23); Pacific Islander and/or Native Hawaiian (1); Multiracial (4) | Evaluate clinic-based screening/referral system effect on community resource receipt | |

| Zielinski et al 2017 | Observational only | Primary care pediatric practice serving a low-income population in Rochester New York | NR | 602 | NR | NR | Evaluate WE CARE screen integration feasibility/acceptability to increase psychosocial needs detection and referrals | |

| FAMNEEDS | Uwemedimo and May 2018 | Observational only | Hospital-based pediatric ambulatory practice in New York City New York | 0–18 | 299 | NR | African American (30); white (8); Hispanic (34); other (26) | Determine FAMNEEDS integration impact on referrals/receipt of social service resources in immigrant families |

| Child ACE Tool | Marie-Mitchell and O’Connor 2013 | Observational only | FQHC serving an urban population | 0–5 | 102 | 0.51 | African American (57); Hispanic (43) | Pilot test ACEs screening tool and explore tool’s ability to distinguish early child outcomes |

| Social History Template of the Standard Well Child Care Form embedded in E-health Record | Beck et al 2012 | Observational only | Hospital-based pediatric clinic serving an urban population in Cincinnati, Ohio | 0–5 | 639 | 48 | African American (71); white (20); other (9) | Determine social risk documentation rates using new electronic template |

| Health-Related Social Problems screener | Fleegler et al 2007 | Observational only | Outpatient pediatric clinics serving an urban population in Boston, Massachusetts and Maryland | 0–6 | 205 | 52 | African American (28); Hispanic (57); other (15) | Characterize cumulative burdens of health-related social problems and evaluate screening/referral acceptability |

Note: ASK=Addressing Social Key Questions for Health, FAMNEEDS=Family Needs Screening Program, FMI=Family Map Inventories, FQHC=federally qualified health center, NR=not reported, OC=observational with comparison group, RCT=randomized controlled trial.

Screener Characteristics

Table 2 provides a detailed overview of the characteristics of the 11 unique SDOH screening tools identified. The majority (8 screeners) were designed for use in doctor’s offices or pediatricians’ clinics. In all cases, parents or caregivers served as the primary informants. Two screeners incorporated additional information from social workers or physicians. Screening methods varied, including paper-and-pencil questionnaires, computer or tablet-based tools, face-to-face interviews, and phone interviews. All screeners were available in English, with seven also offered in Spanish. Three screeners had undergone validity and/or reliability assessments in at least one study, indicating a focus on psychometric rigor for some tools.

TABLE 2. Screening Tool Characteristics

| Screening Tool | Screening Setting | Screening Method | Informant | Training for Screening Professionals | Average Time to Complete Screener, min | Available Languages | Appropriate for Low-Literacy Populations | Validity and/or Reliability Assessed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEEK PSQ | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Paper and pencil; computer or tablet | Parent or caregiver | Yes | 3–4 | English; Spanish | NR | Yes |

| iScreen | Hospital | Computer or tablet; face-to-face interview; or phone interview | Parent or caregiver | Yes | 10 | English; Spanish | Yes | No |

| HealthBegins Upstream Risks Screening Tool | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Face-to-face interview | Parent or caregiver | Yes | 6 | English | NR | No |

| FMI | Home | Face-to-face interview | Parent or caregiver; social worker | Yes | NR | English | NR | No |

| ASK Tool | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Paper and pencil | Parent or caregiver | Yes | NR | English; Spanish | NR | No |

| IHELP | Hospital | Face-to-face interview | Parent or caregiver | Yes | NR | English | NR | Yes (validity only) |

| WE CARE survey instrument | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Paper and pencil | Parent or caregiver | NR | 4–5 | English; Spanish | Yes | Yes |

| FAMNEEDS | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Paper and pencil | Parent or caregiver | Yes | NR | English; Spanish; Haitian Creole; Urdu; Punjabi; Hindi; Arabic | NR | No |

| Child ACE Tool | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Paper and pencil | Parent or caregiver; physician | NR | 5 | English; Spanish | NR | No |

| Social History Template of the Standard Well Child Care Form embedded in E-health Record | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Face-to-face interview | Parent or caregiver | NR | NR | English | NR | No |

| Health-Related Social Problems screener | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Computer or tablet | Parent or caregiver | NR | 20 | English; Spanish | Yes | No |

Note: ASK=Addressing Social Key Questions for Health, FAMNEEDS=Family Needs Screening Program, FMI=Family Map Inventories, NR=not reported.

Regarding the timeframe for SDOH questions, most screeners (6) lacked a clearly defined reference period. For others, reference periods varied by question, and only two screeners had a consistent, defined period for all questions. In terms of screener development, only four reported being informed by practice and/or expert opinion. The remaining screeners were adaptations of existing tools or lacked clear development details.

SDOH Domains

Table 3 outlines the specific SDOH domains assessed by each screening tool. Given the frequent assessment of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which often occur within the family context, we added “family context” as an additional domain to the Healthy People 2020 framework. The family context domain was assessed by all screeners, and economic stability was assessed by all but one. Common elements in the family context domain included household violence, child abuse/neglect, and parental mental health or substance abuse. Economic stability assessments commonly included food insecurity, housing instability, and difficulty paying bills. Education, health and health care, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context domains were assessed by varying numbers of screeners, focusing on areas like parental education, child care access, health insurance status, housing conditions, safety, immigration concerns, discrimination, and social support. Notably, four screeners also assessed protective factors within the family and social/community context domains, such as family closeness, caring adult relationships for children, religious affiliation, and parental social support.

TABLE 3. SDOH Domains

| Screening Tool | Economic Stability | Education | Health and Health Care | Neighborhood and Built Environment | Social and Community Context | Family Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEEK PSQ | Food insufficiency | — | Smoke alarm needed, Poison Control contact | — | — | Parental intimate partner violence, Parental depression, Parental stress, Parental drug/alcohol problems, Tobacco use, Gun in home, Need help with child |

| iScreen | Food insufficiency, Housing instability, Difficulty paying bills, Job problems, Disability impacting work, Difficulty getting income support, Concerns about pregnancy benefits | Concerns child not getting services, Lack of child care | No/inadequate health insurance, Difficulty getting health care, Mental health concerns, No regular provider, Tobacco smoke exposure, Child physical activity concerns | Housing conditions concerns, Transportation difficulties, Safety threats at school/neighborhood, Difficulty getting benefits/services, Childcare activity concerns | Immigration status concerns, Drug/alcohol problems in household, Incarceration, Child support/custody problems | Violence towards child in household |

| HealthBegins Upstream Risks Screening Tool | Food insufficiency, Housing instability, Difficulty making ends meet, Parental employment | Parental education, Concerns about child’s learning/behavior | Parental physical activity, Fruit/vegetable consumption | Housing conditions concerns, Transportation difficulties, Neighborhood safety concerns | Immigration status concerns, Religious/organizational affiliation, Parental social support, Marital status | Parental intimate partner violence victimization, Parental stress |

| FMI | Food insufficiency, Housing instability | — | — | — | — | Child physical abuse, Sexual abuse, Emotional abuse, Maternal intimate partner violence, Household mental illness/substance abuse, Parental separation/divorce, Family closeness |

| ASK Tool | Food insufficiency, Housing instability/bill difficulty, Parental employment | Parental education, Lack of child care | — | Child witnessed violence, Child bullying | — | Child physical abuse, Sexual abuse, Parental mental illness/substance abuse, Need for legal aid, Child separation from caregiver, Adult who comforts child |

| IHELP | Food insufficiency, Housing instability | Concerns about child’s educational needs | Child’s health insurance concerns | Housing conditions concerns | — | Household violence |

| WE CARE survey instrument | Food insufficiency, Housing instability, Difficulty paying bills, Parental employment | Parental education, Lack of child care | — | — | — | Intimate partner violence, Parental depressive symptoms, Alcohol/drug abuse in household |

| FAMNEEDS | Food insufficiency, Housing instability, Difficulty paying bills, Meeting basic needs difficulty, Need public benefits, Need job, Unfairly fired, Need legal aid | Parental education, Need child/elderly care, Health literacy | Need help getting health insurance, Transportation problems preventing care, Parental tobacco/alcohol/drug use | Housing conditions concerns | Parental discrimination experience, Social support | Parental violence/depressive symptoms |

| Child ACE Tool | — | Parental education | — | — | — | Suspected child maltreatment, Intimate partner violence, Household mental illness/substance abuse, Incarceration, Marital status |

| Social History Template of Standard Well Child Care Form | Food insufficiency, Difficulty making ends meet, Difficulty getting income support | — | — | Housing conditions concerns | — | Parental depressive symptoms, Parent/child safety |

| Health-Related Social Problems screener | Food insufficiency, Housing instability, Difficulty paying bills, Income support use, Parental employment, Household income | — | Parent/child health insurance, No regular provider, Problems receiving care | Housing conditions concerns | — | Parental intimate partner violence victimization |

Note: ASK=Addressing Social Key Questions for Health, FAMNEEDS=Family Needs Screening Program, FMI=Family Map Inventories, —=not assessed.

Follow-up Procedures

Table 4 details the follow-up procedures associated with SDOH screening in the reviewed studies. A minority of studies (4) reported no specific follow-up procedures. In six studies, screening results were discussed with caregivers, and referrals to community resources were offered, but no direct interventions were described. Three studies reported offering referrals without mentioning discussion of results or interventions. Only three studies documented a comprehensive approach involving discussion of results, referral provision, and active intervention. Interventions included motivational interviewing techniques by providers and the use of navigators to assist families in accessing and understanding community resources.

TABLE 4. Follow-up Procedures

| Screening Tool | Author and Year | Results Discussed | Referral Offered and/or Scheduled | Intervention Delivered | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEEK PSQ | Dubowitz et al 2007 | — | — | — | No follow-up reported. |

| Dubowitz et al 2009 | X | X | — | Trained residents provided parents with resource handouts, involved social worker, and made community referrals. | |

| Dubowitz et al 2012 | X | X | — | Practitioners provided customized resource handouts; social worker available for support, crisis intervention, and referrals. | |

| Eismann et al 2018 | X | X | X | Providers used motivational interviewing, offered resources/referrals, social worker available by phone for referral assistance. | |

| iScreen | Gottlieb et al 2014 | — | — | — | No follow-up reported. |

| Gottlieb et al 2016 | X | X | X | Caregivers received written information (control) or in-person navigation with follow-up calls (intervention) to access community resources. | |

| HealthBegins Upstream Risks Screening Tool | Hensley et al 2017 | X | X | — | At-risk results linked to community resource guide; assistance offered for contacting resources. |

| FMI | McKelvey et al 2016 | — | — | X | Screening at home visiting program implementation (2-generation programs for at-risk families). |

| ASK Tool | Selvaraj et al 2018 | X | X | — | Clinicians discussed results, referred to community resources using developed lists; social worker consultation for complex needs. |

| IHELP | Colvin et al 2016 | — | X | — | Interns provided referrals for social work consultation. |

| WE CARE survey instrument | Garg et al 2007 | X | X | — | Residents reviewed survey, referred if parents wanted assistance, provided Family Resource Book pages. |

| Garg et al 2015 | X | X | — | Clinicians reviewed survey, offered 1-page resource sheets with 2-4 community resources. | |

| Zielinski et al 2017 | — | X | — | Positive screen triggered social work referral. | |

| FAMNEEDS | Uwemedimo and May 2018 | X | X | X | Resource navigator follow-up calls, provided social service contacts, e-referrals, bi-weekly follow-up for 8 weeks. |

| Child ACE Tool | Marie-Mitchell and O’Connor 2013 | — | — | — | No follow-up reported. |

| Social History Template of Standard Well Child Care Form | Beck et al 2012 | — | — | — | No follow-up reported |

| Health-Related Social problems screener | Fleegler et al 2007 | — | X | — | All participants received referral sheet listing local agencies. |

Note: ASK=Addressing Social key Questions for Health, FAMNEEDS=Family Needs Screening Program, FMI=Family Map Inventories, —=not assessed.

Discussion

This review identified 11 distinct social determinants of health screening tools used in pediatric settings. It’s noteworthy that all identified articles describing these tools were published within the last 12 years, reflecting a recent surge in interest and research in this area. This trend mirrors the growing recognition of SDOHs within the broader medical community. Organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics have been advocating for standardized SDOH screening in pediatric practice since the early 2000s, aiming to identify and address social and behavioral risk factors relevant to patient populations. The increasing policy emphasis, exemplified by North Carolina’s Medicaid requirement for SDOH screening, suggests that this practice is likely to expand further. Therefore, understanding the characteristics, validity, and impact of existing SDOH screening tools is crucial.

Our review reveals that while many screeners demonstrate strengths in areas like validation, population relevance, and follow-up mechanisms, few comprehensively incorporate all three. A key concern highlighted by our analysis is the limited assessment of the psychometric properties of these tools. Only three of the 11 screeners had undergone rigorous reliability and/or validity testing. This raises questions about the accuracy of most tools in measuring children’s SDOHs. Several factors can influence the accuracy of screening results, including the tool’s language accessibility, reading level appropriateness, and clarity of reference periods for SDOH questions. While most reviewed tools were available in multiple languages, and some were designed for low-literacy populations, a significant number lacked a clear and consistent reference period, potentially impacting the reliability of informant responses. Furthermore, few screeners assessed the chronicity or duration of SDOH experiences, crucial information for tailoring effective interventions and referrals. The limited attention to reference periods and SDOH duration highlights an area for improvement in future tool development and research.

The reliance on parent and caregiver reports as the primary source of information for all assessed tools is another important consideration. While these informants often possess the most intimate knowledge of a child’s social context, they may also be susceptible to social desirability bias or fear of repercussions from child protective services, potentially influencing their responses. Triangulating information with other sources, such as physician or social worker observations, or incorporating child self-report, could enhance the robustness of SDOH assessments. However, such multi-source approaches may require additional resources and logistical considerations.

To mitigate potential biases and improve the acceptability of screening, many tool developers have incorporated input from community members, experts, and practice experience. The SEEK Parent Screening Questionnaire (PSQ), for example, was developed with input from community pediatricians and parents, emphasizing an empathetic approach and conveying the practice’s commitment to supporting families. Future research could explore the impact of such empathetic framing on reducing social desirability bias by empirically testing alongside social desirability scales.

Reflecting the recommendation of the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children to tailor SDOH screening to local needs and resources, most screeners in our review focused on SDOHs for which community resources were available. The WE CARE screener exemplifies this approach. Contrary to concerns about lack of follow-up for ACE screening, our review found that most studies reported immediate referrals and/or interventions following SDOH screening. However, the actual effectiveness of these referrals and interventions in addressing family needs and improving child health outcomes remains an area requiring further investigation. Additionally, the limited assessment of protective factors in most screeners suggests a predominantly deficit-based approach to follow-up interventions. Incorporating strength-based assessments and interventions, which build upon existing family and community assets, could enhance the effectiveness and positive impact of SDOH screening in pediatric primary care.

While our search strategy was not limited to clinical settings, nearly all identified screeners were used in pediatric clinics or hospitals. Educational settings, which offer universal access to children and adolescents, present an underutilized opportunity for SDOH screening. Trauma screening tools are already used in schools for targeted populations, but universal SDOH screening in educational settings has not gained the same traction as in healthcare, despite the well-documented impact of SDOHs on educational attainment and well-being. Exploring the feasibility and effectiveness of SDOH screening in schools warrants further attention.

Limitations

This review has some limitations. The use of the Healthy People 2020 definition of SDOHs may have excluded studies employing alternative definitions. Furthermore, our focus on SDOH measures meant we did not collect outcome data, limiting our ability to determine which SDOH domains have the most significant impact on child health. Despite these limitations, this review offers significant strengths, including a comprehensive search strategy that identified a broad range of SDOH screening tools used in research and practice. To our knowledge, this is the first review to systematically assess both the psychometric properties of SDOH screening tools and the associated follow-up procedures.

Conclusion

The social determinants of health screening tools identified in this review demonstrate a growing effort to address the social context of children’s health within pediatric primary care. Many tools are thoughtfully designed to be relevant to specific populations and are often linked to follow-up referrals and interventions. However, significant gaps remain, particularly in the rigorous evaluation of the validity and reliability of these tools and in assessing the effectiveness of post-screening interventions. As SDOH screening becomes increasingly prevalent, future research should prioritize these areas to ensure that screening efforts translate into meaningful improvements in child well-being. Moreover, tool developers should consider expanding the applicability of SDOH screening beyond medical settings to reach children and families in diverse contexts, such as educational environments, to promote equitable access to support and resources.

Supplementary Material

Data Supplement: NIHMS1067610-supplement-Data_Supplement.pdf

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (R49 CE002479), and the National Institute of Child Health and Development (T32 HD52468, T32 HD007376).

Abbreviations

- ACE: adverse childhood experience

- PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- PSQ: Parent Screening Questionnaire

- SDOH: social determinant of health

- SEEK: Safe Environment for Every Kid

- WE CARE: Well Child Care Evaluation Community Resources Advocacy Referral Education

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare no financial conflicts of interest.

Potential Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Companion Paper: A related article is available online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2019-2395.

References

(Implicitly uses the references from the original article, as per instructions)

Associated Data

Supplementary Materials

Data Supplement: NIHMS1067610-supplement-Data_Supplement.pdf