INTRODUCTION

In today’s fast-paced healthcare environment, nurses face immense pressure to stay updated with the latest evidence-based practices while managing demanding workloads. Many nurses report feeling challenged in meeting standardized competencies due to time constraints from staffing issues, competing patient care demands, limited organizational support, and insufficient training [1]. Point-of-care tools (PoCTs) have emerged as crucial resources for healthcare professionals, offering synthesized evidence-based information directly at the patient’s bedside. These tools integrate knowledge from health sciences literature, practice guidelines, and other relevant sources on diseases, conditions, and procedures. Beyond immediate clinical utility, PoCTs also support clinicians’ ongoing professional development [2, 3]. With a plethora of PoCTs available, healthcare organizations and individual practitioners must discern which tools provide high-quality evidence through user-friendly interfaces, enabling nurses to efficiently answer clinical questions at the point of care [4, 5, 6].

However, research specifically examining how well PoCTs address the unique information needs of nurses remains limited [6]. Prior studies often focus on other healthcare disciplines or broadly assess PoCT credibility. Research comparing content presentation across different PoCTs has revealed variations, highlighting inconsistencies in content generation transparency and editorial processes [4, 5, 7]. A recurring finding is that no single PoCT fulfills all evaluation criteria perfectly, suggesting the value of utilizing multiple PoCTs for comprehensive information access [4, 5, 7]. While user experience studies have explored PoCTs among health science students and clinicians generally, discipline-specific perspectives, especially from registered nurses, are less understood. User satisfaction is a key predictor of future PoCT usage, regardless of perceived content quality [8, 9].

Recognizing the unique information needs of nurses is critical. Clarke’s work [10] highlights that while physicians often focus on diagnoses, nurses more frequently seek information on protocols and procedures, although both disciplines require treatment information. Studies comparing nursing-centric PoCTs with general medical PoCTs show that nursing-specific tools offer more relevant content for nurses [11] and are considered useful in their clinical practice [6]. Therefore, direct-care registered nurses’ input is vital in the decision-making process when selecting PoCTs for healthcare organizations.

Prompted by nurses’ shared governance at the University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System (UIH) in 2019, an evaluation of nursing PoCTs was initiated to recommend the best tool for nursing practice. Nursing Reference Center Plus (NRC+), licensed by the University of Illinois Chicago since 2009, had seen declining usage, raising questions about its renewal. Alongside NRC+, the library also licensed UpToDate and other PoCTs for clinicians. While the council initially aimed to assess other nursing PoCTs in early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused delays.

In the interim, University of Illinois Chicago nursing librarians conducted an internal analysis of five PoCTs: ClinicalKey for Nursing (CK Nursing), DynaMed, Lippincott Nursing Advisor and Procedures, NRC+, and UpToDate. Their evaluation focused on content, nursing topic coverage, transparency, customization, and user perception. Their findings echoed previous research: no single PoCT is ideal, each has strengths and weaknesses, and brand recognition is not a reliable indicator of quality [4, 7]. From a nursing-centric perspective, they noted that UpToDate and DynaMed might be better suited for advanced practice nurses, while NRC+, CK Nursing, and Lippincott focused more on core nursing measures, cultural competencies, and interventions relevant to direct care nurses.

This study aimed to compare three PoCTs – NRC+, CK Nursing, and UpToDate – based on content clarity, result relevance, information currency, navigation ease, and familiarity, to identify which best meets registered nurses’ information needs within our organization. Building on prior research [11], we hypothesized that a nursing-focused PoCT would better address registered nurses’ information needs compared to UpToDate, which is designed for a broader provider audience.

METHODS

A quantitative descriptive design was employed, using an online survey to compare NRC+, CK Nursing, and UpToDate. The survey design was adapted from Campbell’s study [5], incorporating feedback from nursing leadership and the Advanced Practice and Research Council. Clinical questions were refined for clarity by a panel of sixteen clinical experts.

NRC+ and UpToDate were selected because of existing library licenses. ClinicalKey for Nursing was included due to nursing leadership interest and a trial subscription was obtained. Despite acknowledging UpToDate’s physician and advanced practice nurse orientation, it was included to represent a non-nursing-focused alternative should nursing-specific PoCTs be unavailable.

Setting and Sample

The study took place at a 462-bed university hospital in a major Midwestern city. A convenience sample of 1,150 staff nurses and clinical nurse educators was targeted. The University of Illinois Chicago Institutional Review Board approved the study as exempt (protocol 2020-1455).

Recruitment and Data Collection

Participants were recruited via email to registered nurse mailing lists, flyers in hospital breakrooms, and announcements at nursing council meetings. Self-selection occurred when nurses followed a survey link in the recruitment materials. No identifying information was collected within the survey itself. A separate survey link was provided for participants to enter contact details for an Amazon gift card raffle, with contact information deleted after gift card distribution. Data collection spanned from November 18, 2020, to December 31, 2020, with email reminders sent bi-weekly and then weekly before closure.

Informed consent was implied by survey participation, with a statement at the survey’s start. Participants chose a clinical question category (guidelines and disease understanding, assessment and diagnosis, or nursing interventions and medication information) and then searched for answers to three predetermined questions within each PoCT, spending about three minutes per question. This brief timeframe simulated clinical urgency and aligned with Campbell’s methodology [5].

Surveys assessed end-user experience across six criteria (Table 1): content clarity (layout), result relevance, information currency, navigation ease, labeling, and filter usability (full survey in Appendix A).

Table 1. Evaluation Criteria for Likert Questions

| Criteria | Definition |

|---|---|

| Clarity of content (layout) | Information (content) displayed on the screen was clear and concise |

| Relevance of results | Relevance of the results displayed was highly applicable to the clinical question |

| Currency of displayed information | Information displayed appeared to be the most recent available |

| Ease of navigation | Site was intuitive and easy to navigate |

| Labeling | Content was clearly labeled (e.g., headers, links) |

| Use of filters | The use of filters to refine the search was user friendly (e.g., age of patient) |

Nurses rated their experience on a 7-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 7=strongly agree). PoCT familiarity was rated from 0 (“not at all familiar”) to 5 (“very familiar”). Other questions included prior PoCT use (yes/no) and mobile app usage (yes/no). Open-ended questions explored likes, dislikes, and overall opinions of each PoCT. Demographic data collected included practice area, employment status, nursing experience, and education level. Survey completion took approximately thirty minutes.

Data Analysis

Qualtrics, Excel, and SPSS were used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies, percentages) were calculated. ANOVA compared overall ratings of tool features (layout, relevance, currency, navigation, labeling, filters) across the three PoCTs. A p<0.05 significance level was used. Open-ended responses were analyzed independently by authors using inductive content analysis to identify themes [12]. This inductive approach allowed for discovery of emergent evaluation criteria and opinions. Authors resolved discrepancies through discussion and consensus, using Excel for data organization. Multiple themes could be applied to each response. Themes of “Positive” and “Negative” were applied to comments generally favorable or critical of each PoCT, regardless of specific feature mentions.

RESULTS

Demographics

Of 177 nurses starting the survey, 76 completed it, resulting in a 6.6% final response rate from the hospital system’s nurses.

The majority held a bachelor’s (51%) or master’s (36%) degree. About 6% had an associate’s degree or diploma, and 7% a doctoral degree. Most worked in inpatient units (71%) and were full-time (89%). Nursing experience ranged from 0-5 years (35%), 6-15 years (30%), to over 20 years (30%). No significant differences in PoCT ratings were found based on education level, inpatient/outpatient status, employment status, or years of experience.

Participant Ratings

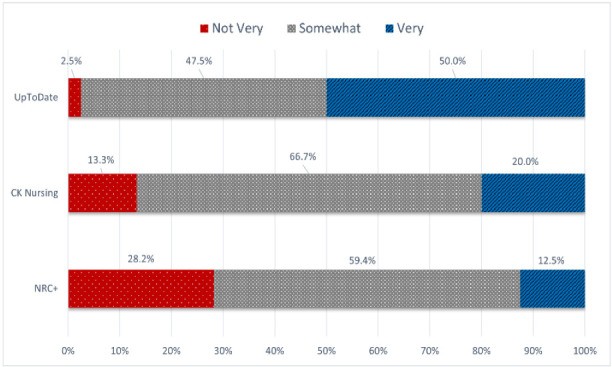

Prior usage and familiarity with each PoCT were assessed. 42% reported using NRC+, 53% UpToDate, and 20% CK Nursing previously. Figure 1 illustrates familiarity levels among prior users, categorized as not very familiar (0-2), somewhat familiar (3-4), and very familiar (5).

Figure 1. Nurses’ stated familiarity with PoCTs

Figure 2

Figure 2

Likert scale ratings for features and characteristics are in Table 2. ANOVA showed no statistically significant difference in overall feature ratings across PoCTs (Tool 1: x̅=6.22; Tool 2: x̅=6.19; Tool 3: x̅=5.85 (F=1,81 (2, 72) >.05)). Prior usage, experience, education, or familiarity did not correlate with overall ratings.

Table 2. Perceptions of PoCT features and characteristics. Mean and standard deviation for each PoCT are reported.

| Feature of Interest | NRC+ | CK Nursing | UpToDate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Layout | 5.12 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 5.6 ± 1.2 |

| Relevance | 5.0 ± 1.7 | 5.2 ± 1.4 | 5.6 ± 1.4 |

| Currency | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 5.7 ± 1.2 |

| Navigation | 5.1 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 5.5 ± 1.4 |

| Labeling | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 5.6 ± 1.3 |

| Filters | 4.6 ± 2.0 | 4.5 ± 2.0 | 5.3 ± 1.5 |

Participants’ Comments about PoCTs

Fifty-five participants (72%) answered open-ended questions. Responses were typically short, often single words or sentences. Themes emerging from these responses related to PoCT characteristics and user experience included: Accessibility, Audience, Content, CE (Continuing Education), Currency, Drugs, Familiarity, Filtering, Findability/Search, Guidelines, Information Amount, Layout, Mobile Application, Navigation, Organization, Negative feedback, Positive feedback, Procedures, Relevance, Simplicity, Trust/Reliability, User Friendliness, Visuals, and Other.

Nursing Reference Center Plus

NRC+ received the most comments. For “likes” (48 responses), common themes were Simplicity, User Friendliness, Content, Information Amount, and Navigation. Positive comments included “wide range of information,” “one stop resource,” “easy to use interface and navigation,” “easy access via search bar,” and “downloadable app for literature at fingertips.”

For “dislikes” (38 responses), negative comments focused on Findability, Relevance, Information Amount, and Layout. Participants reported “not able to find everything I looked for,” “antiquated navigation,” “difficult to search,” “glitches filtering,” and “sometimes hard to find needed info, most up-to-date things do not always reflect hospital policy.” Several comments indicated difficulty finding information or sifting through irrelevant results.

ClinicalKey for Nursing

For “likes” about CK Nursing (38 responses), common themes were Simplicity, User Friendliness, Navigation, Content, and Findability. Positive filtering capabilities were noted, unlike with NRC+. Comments included “easier to navigate,” “better search results/filter use actually works,” “clear and right to the point, very nursing related and specific,” and comparisons like “easier to use than the first” and “better than previous…relevant clinical skills assessment checklists and videos/images related to each question.”

For “dislikes” (32 responses), common themes were Findability, Content, Relevance, and Other. Participants also struggled finding answers in CK Nursing. Comments included “results show up like a Google search; no way to differentiate,” “too many irrelevant items at the beginning,” and “search did not have AND/OR option. Should add explanation/descriptor when hovering over each browse or tool option.”

UpToDate

For “likes” about UpToDate (38 responses), common themes were Simplicity, User Friendliness, Navigation, Organization, Content, and Findability. Comments included “love Up to Date because you are able to find the information that you are looking for relatively quick,” “sufficient amount of information,” “go-to resource,” and “excellent for diagnosis and management of disease; knowledge of diagnosis.”

For “dislikes” (37 responses), common themes were Relevance, Findability, Audience, Layout, and Organization. Information searching difficulties were also mentioned. Comments included “text heavy, would like more differentiation in search,” “could not find answers in 3 minutes…no way to…find skills versus date,” and “You have to type exactly what you want to know otherwise it doesn’t seem to know what you are talking about.” UpToDate received the most negative comments regarding nursing suitability, such as “Medical focused, not Nursing focused” and “more appropriate for diagnosing clinicians, not for nurses…answers more related to diagnosing than to nursing assessment.”

Previously Used PoCTs and Resources

Participants were asked about other resources used (Table 3). Over two-thirds used CINAHL and PubMed, and nearly half used Lippincott Nursing products.

Table 3. Other PoCTs and resources respondents used previously

| PoCTs and Resources | Percentage of Respondents |

|---|---|

| CINAHL | 75% |

| PubMed | 66% |

| Lippincott Nursing Products | 41% |

| Cochrane Library | 29% |

| Medline via Ovid | 26% |

| DynaMed | 13% |

| APA PsycINFO | 9% |

| Other, please specify[*] | 3% |

[*]Other resources reported: DePaul online library search; ScienceDirect.

DISCUSSION

The relatively even distribution of opinions across PoCTs was unexpected. We anticipated a nursing-specific PoCT to be preferred due to tailored content like care plans, procedural checklists, videos, and CE materials. We also expected higher ratings from those familiar with PoCTs. However, nursing education or experience showed no correlation with PoCT preference or Likert ratings.

Several comments revealed a possible lack of understanding about PoCT purpose and effective search strategies among some nurses:

“Could be improved to include relevant info for bedside nurses at UIH aka protocols applicable to me.”

“Easier to filter. Fine if you’re researching something, like for school or a project. But not really helpful when you’re working on the floor.”

“Best research app available, free for me, easy to navigate …”

“That you can search for your topic in the form of a question”

While prior research has explored nurses’ information seeking behaviors [13–16], these responses may indicate a need for broader investigation into nurses’ information needs and seeking behaviors. Low overall PoCT ratings and negative search comments across tools suggest participants may expect PoCT search interfaces to function like Google, a potentially primary information source. To improve PoCT effectiveness for nurses, librarians, nursing faculty, and leaders could develop educational interventions clarifying when to use CINAHL, PoCTs, or Google.

The comment “the nurses and doctors should all be using the same information/resources” is concerning. Healthcare professionals have diverse information needs based on practice level and interprofessional interactions. Literature consistently suggests licensing multiple PoCTs, as no single tool meets all user needs [4, 7, 11]. Further training may be needed to emphasize the appropriateness of nursing-specific resources for registered nurses’ clinical practice.

Engaging PoCT vendors to improve search algorithms and user experience is another avenue. Vendors could incorporate more prominent feedback mechanisms for end-users to suggest improvements. Given mixed search result reviews, algorithm adjustments may be needed. Usability studies with nurses could identify search behaviors and content needs. Participants’ desire for images and videos suggests vendors should integrate multimedia content or enhance its discoverability. More prominent user guides within PoCTs could also aid searching.

Vendors should also ensure content accessibility, meeting standardized accessibility guidelines like those from the Big Ten Academic Alliance Libraries [17]. While some participants found screens “easy to read,” font size adjustment requests indicate room for improvement. Librarians should advocate for accessibility and prioritize it in PoCT selection.

Similar PoCT ratings across categories and demographics, coupled with UpToDate’s higher familiarity, were notable. NRC+’s lower familiarity was surprising given promotional efforts, including hospital-wide demonstrations by EBSCO and author-led training. However, lack of formal nursing leadership endorsement of NRC+ may have hindered adoption. NRC+’s original package licensing highlights the importance of stakeholder consensus when licensing new PoCTs, even though resource allocation is ultimately the library’s decision.

UpToDate’s limited navigation options, while perceived negatively by librarians, did not bother nurses, reflecting a trend towards simpler interfaces. Users often equate simplicity with straightforward results, overlooking the benefits of sophisticated searches [18]. While NRC+ is recognized by health science librarians, nurses may not share this familiarity. UpToDate and CK Nursing, but not NRC+, were described as “trusted” or “reliable.” Marketing research shows consumer preference for familiar brands [19]. Nurses may equate trust with brand recognition or perceive PoCT authority based on educational use or physician/clinician use. UIH nurses may not have recognized NRC+ as comparable to CK Nursing or UpToDate, potentially contributing to its underutilization. Further research is needed to understand nurses’ perceptions of PoCTs and library resources, and to compare librarian and nurse perspectives on PoCT utility.

Limitations

The relatively small sample size and survey timing during the COVID-19 pandemic and a new electronic health record system implementation may have affected participation and generalizability. The 6.6% response rate and ~50% completion rate among those starting the survey also limit generalizability within and beyond the organization. Self-selection bias may have led to overrepresentation of nurses interested in PoCTs, potentially inflating favorable ratings. The survey, while based on a prior study and expert-developed questions, was not formally validated.

Presenting PoCTs in a fixed order may have introduced a “practice effect” [20], where familiarity with survey questions, rather than PoCTs themselves, influenced higher ratings for later tools. Also, allowing free-text search terms, instead of standardized terms, means search result satisfaction could reflect PoCT performance or participant search skills. However, this approach mirrors real-world PoCT usage. Future research should randomize tool order and track search terms.

User surveys offer only one perspective on tool utility. Ease of use is paramount [21]. Future studies should incorporate user experience research methods [22], including first-click analysis, eye-tracking, screen recording, and usability evaluation tools [23], to better understand PoCT preferences.

CONCLUSION

Including nurses’ perspectives on PoCTs is essential. Consistent with prior research, more nurses need training for effective PoCT utilization [6,13–14], offering librarians opportunities to educate on best search practices. Collaboration between librarians and hospital leadership is crucial. If hospitals prioritize PoCTs, leadership must communicate their importance and provide regular training opportunities during orientations, unit meetings, and ongoing sessions.

Following the survey, a summary report was shared with the Advanced Practice and Research Council and nursing leadership. Given the mixed feedback on nursing PoCTs and leadership’s desire for interprofessional resource focus, other options were explored. Dynamic Health and Lippincott’s Nursing products were reviewed, leading to the decision to license Lippincott’s Nursing products. NRC+ was discontinued in June 2021.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jung-Mi Scoulas, Assessment Coordinator, and the Advanced Practice and Research Council at University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System for survey feedback. Thanks also to Sandra De Groote, Head of Assessment and Scholarly Communications, for data analysis assistance, and Glenda Insua, Reference and Liaison Librarian, for revision assistance.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

A cleaned, deidentified dataset will be available in the University of Illinois Chicago institutional repository: 10.25417/uic.19287809.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Annie Nickum: Study conception and design; literature review; visualization; writing—original draft, reviewing and editing; quantitative analysis. Rebecca Raszewski: Study conception and design, survey development, qualitative analysis, literature review; reviewing and editing. Susan C. Vonderheid: Study conception and design, data collection, literature review, survey development, reviewing and editing, interpretation of results. All authors reviewed results and approved the final manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTAL FILES

jmla-110-3-323-s01.pdf (173.7KB, pdf) Appendix A: Nursing Point-of-Care Tools Evaluation

REFERENCES

[1] Bloomfield JG, Roberts MJ, While AE. The effect of continuing professional development on job satisfaction and retention: a systematic review. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2010 Winter;30(1):17-28. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/chp.20050.

[2] Dawes M, Sampson C, Shojania KG. Point-of-care information retrieval. In: Mayer D, ed. Evidence-based practice for nurses and healthcare professionals. London: Interprofessional. 2010:103-27.

[3] Kleinpell RM. Using point-of-care resources to facilitate evidence-based practice. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2010 Oct-Dec;21(4):352-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NCI.0b013e3181f76d47.

[4] Banzi R, Liberati A, Stock C, Jamtvedt G, Kuhn-Light MK, McIntosh N, Sterne JA, Kleijnen J. Interventions to improve the use of systematic reviews in clinical practice and health policy. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15 Suppl 1:iii-iv, 1-170.

[5] Campbell J. Evaluation of point-of-care information summary tools. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2011;8(2):94-101. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00215.x.

[6] Eldredge JD, von Ville H, Haber J. Point-of-care resources: their content and use in nursing practice. J Med Libr Assoc. 2008 Oct;96(4):313-21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.96.4.313.

[7] Prorok JC, Campbell J, Overbo K, Stasiak P, Clarfield AM. Content validity of point-of-care resources: a systematic review. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2015 Dec;20(6):205-14. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2015-110229.

[8] Flodgren G, Rachid EL, Eccles MP, Shepperd S. Interactive telemedicine: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Sep 29;(9):CD002098. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002098.pub2.

[9] McColl A, Smith H, White P, Field J. General practitioners’ perceptions of the route of referral to specialist out-patient clinics. Fam Pract. 1998 Feb;15(1):65-71. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/fampra/15.1.65.

[10] Clarke MA. Information needs of clinical nurses: an evidence synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2007 Nov;60(4):359-70. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04428.x.

[11] Booth A, Sharpe V, Sutton A. Point of care information sources for nurses: survey of current practice and perceived usefulness. Health Info Libr J. 2011 Jun;28(2):133-44. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2011.00936.x.

[12] Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237-46.

[13] Gerrish K, Clayton J, Atkinson R, Blease J, Hellewell J, Lacey A. Evidence-based practice: nurses’ views and experiences. Br J Nurs. 2004 May 13-26;13(9):501-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2004.13.9.14778.

[14] Kajermo KN, Nordstrom G, Krusebrant A, Blackwell A, Sachs MA, RCG S. Barriers to and facilitators of evidence-based practice among nurses in Sweden–a national survey. J Adv Nurs. 2008 Oct;65(5):1029-40. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04914.x.

[15] Pravikoff DS, Pierce ST, Tanner AB. Readiness of U.S. nurses for evidence-based practice. Am J Nurs. 2005 Sep;105(9):40-51; quiz 51-2.

[16] Majid S, Foo S, Chang YP, Mokhtar IA, Beh PC. Adopting evidence-based practice in clinical decisions: nurses’ perceptions, knowledge, and barriers. J Med Libr Assoc. 2011 Oct;99(4):229-36. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.99.4.005.

[17] Big Ten Academic Alliance Libraries. Accessibility license language. [cited 19 Aug 2021]. https://www.btaa.org/library/initiatives/accessibility/accessibility-license-language.

[18] Nicholas D, Huntington P, Williams P, Dobrowolski T. Re-appraising information seeking behaviour in a digital environment: bouncers, checkers, returnees and the like. J Doc. 2012 Jul 13;68(5):731-53. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00220411211256025.

[19] Van Osselaer SM, Alba JW. Locus of equity and brand extension success. J Mark Res. 2000 May;37(2):165-79. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.37.2.165.17604.

[20] Calamia M, Markon KE, Haaland KY. Equating practice effects, attrition, and malingering in clinical neuropsychology: a preliminary investigation. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2008 Mar;30(2):209-15. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13803390701330846.

[21] Nielsen J. Usability engineering. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann; 1993.

[22] Rubin J, Chisnell D. Handbook of usability testing: how to plan, design, and conduct effective tests. 2nd ed. Indianapolis, IN: Wiley Publishing, Inc.; 2008.

[23] Tullis T, Albert B. Measuring the user experience. Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann; 2008.