I. Introduction

Providing accurate prognostic information is paramount in palliative care, enabling informed decision-making for patients nearing the end of life. It’s well-documented that patients often hold overly optimistic or inaccurate perceptions of their prognosis [1-5]. While patients expect honest and realistic survival estimates from their physicians [6, 7], clinical predictions, although generally more accurate than patient self-assessments [1, 5], still exhibit considerable inaccuracy [8, 9]. Consequently, clinical guidelines advocate for supplementing clinical judgment with validated prognostic algorithms [10, 11]. Numerous prognostic tools have been developed for advanced cancer patients [12, 13], yet relatively few have been rigorously compared against clinicians’ own survival predictions [14-18]. This study delves into the comparative effectiveness of several established Palliative Care Prognostic Tools against clinical predictions of survival.

The Prognosis in Palliative Care Study (PiPS) was a pioneering multi-center prospective study aimed at developing and validating a prognostic tool tailored for cancer palliative care [19]. This research led to the creation of prognostic models, PiPS-A and PiPS-B, predicting 14-day and 56-day survival, categorized by whether blood test results were available. PiPS-A and PiPS-B risk categories demonstrated accuracy comparable to joint doctor-nurse survival estimates [19]. The subsequent PiPS2 study [20] prospectively validated these PiPS models alongside other prognostic tools, confirming the excellent discrimination and calibration of PiPS-A14, PiPS-A56, PiPS-B14, and PiPS-B56. However, only PiPS-B risk categories matched the accuracy of multi-professional survival estimates [21].

Beyond PiPS validation, the PiPS2 study extended its scope to evaluate four additional palliative care prognostic tools: the Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI) [22], the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) [23], the Palliative Prognostic (PaP) score [24], and the Feliu Prognostic Nomogram (FPN) [25]. Notably, PPI and PPS, like PiPS-A, can be calculated without blood tests, while PaP and FPN, similar to PiPS-B, require blood test results. This article focuses on the evaluation of these four prognostic scores within a cohort of advanced incurable cancer patients, specifically comparing their prognostic performance against clinicians’ own predictions of survival. This comparison is crucial for determining the clinical utility of these palliative care prognostic tools in real-world palliative care settings.

II. Methods

This validation study employed a multi-center, prospective, cohort design to evaluate the aforementioned palliative care prognostic tools. The study protocol, registered as ISRCTN 13688211, has been previously published [20], and ethical approval was obtained from the Yorkshire and Humber-Leeds East Research Ethics Committee (16/YH/0132).

A. Study Population

Participants were recruited from 27 palliative care services across the UK, encompassing community, hospital, and inpatient palliative care units. The study included adult patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care, with or without the capacity to provide consent. Capacity assessment was performed at each site by the Principal Investigator or a delegate [26]. Patients with capacity provided written informed consent, while for those without capacity, personal or nominated consultees were consulted.

B. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria:

- Diagnosis of incurable cancer.

- Age 18 years or older.

- Recent referral to palliative care services.

- For patients with capacity, ability to understand the Patient Information Sheet. For patients without capacity, consultee approval was necessary.

Exclusion criterion:

Patients undergoing treatment with curative intent were excluded.

C. Data Collection

Baseline prognostic data, essential for calculating each prognostic score, were collected shortly after referral to palliative care services. Data sources included medical record reviews, discussions with clinical staff, and direct patient interviews. Table 1 details the variables required for each prognostic score. Additional data collected for PiPS prognostic scores are detailed elsewhere [21].

Table 1. Variables for Palliative Care Prognostic Tool Calculation

| Variable Type | Variable Name | PaP | FPN | PPI | PPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician Assessments | Clinician Prediction of Survival | x | |||

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) | x | ||||

| Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) | x | ||||

| Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) | x | ||||

| Time to Terminal Disease | x | ||||

| Blood Tests | Albumin | x | x | ||

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) | x | x | |||

| Lymphocyte Count | x | x | x | ||

| White Blood Count (WBC) | x | x | |||

| Clinical Signs & Symptoms | Anorexia | x | x | ||

| Delirium | x | x | |||

| Dyspnea at Rest | x | x | x | ||

| Edema | x | x | |||

| Oral Intake | x | x |

1. Palliative Prognostic (PaP) Score

The PaP score categorizes patients into three risk groups based on 30-day survival probabilities: low (<30%), intermediate (30–70%), and high (>70%). Higher scores indicate poorer prognosis. The score is derived from a weighted sum of six variables: clinician prediction of survival, Karnofsky performance status, anorexia, dyspnea, total white blood count, and lymphocyte percentage.

2. Feliu Prognostic Nomogram (FPN)

FPN predicts survival probabilities at 15, 30, and 60 days using five variables: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status [27], serum albumin, Lactate Dehydrogenase, lymphocyte counts, and time from initial cancer diagnosis to terminal disease diagnosis (TTD).

3. Palliative Performance Scale (PPS)

PPS, a functional status measure specific to palliative care, is scored by healthcare professionals. It comprises 10 categories, ranging from 10% (poorest functional status: bedridden, minimal activity, mouth care only, drowsy/comatose) to 100% (best functional status: fully ambulatory, normal activity, able to self-care, normal food intake, fully conscious).

4. Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI)

PPI utilizes five clinical variables from the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), oral intake, dyspnea, edema, and delirium to stratify patients into three prognostic groups: survival <3 weeks (score >6), survival <6 weeks (score >4), and survival >6 weeks (score ≤4).

5. Clinical Prediction of Survival (CPS)

Attending doctors and nurses independently estimated patient survival. A hierarchical approach was used to generate a composite CPS: doctor predictions were prioritized, and nurse predictions were used when doctor predictions were unavailable. Clinicians provided estimates in various formats: approximate survival lengths (“days,” “weeks,” “months+”), specific survival estimates to the nearest week (up to 12 weeks), and probabilities of survival at 1, 3, 7, 15, 30, and 60 days.

Clinician demographics, including age, gender, specialty, years of experience, and professional grade, were collected anonymously.

6. Survival Outcome

Dates of death were obtained from NHS Digital (https://digital.nhs.uk/) at least three months post-recruitment completion.

D. Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

The primary outcomes were patient survival from enrollment, clinician survival predictions, and prognostic scores. Absolute patient survival served as the gold standard for evaluating the palliative care prognostic tools and clinician performance. Tool performance was also compared directly against clinical predictions of survival.

1. Sample Size

The study’s sample size of 1833 participants was primarily determined for validating PiPS-B risk categories, requiring at least 100 events [28], inflated to 150 for conservatism. Based on an anticipated 17.8% event rate, 843 patients were deemed necessary for PiPS-B validation. This sample size was considered sufficient for validating the other palliative care prognostic tools (PPI, PPS, PaP, and FPN) as well.

2. Statistical Analysis

Prognostic tools were evaluated in their original intended forms. Discrimination, the ability to differentiate between risk groups, was assessed using the C-statistic (binary outcomes) and Harrell’s C-index (survival outcomes), and graphically via Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Calibration, the agreement between predicted and observed outcomes, was assessed using calibration slopes (Cox model for FPN [29]) and by comparing predicted and observed survival proportions at specific time points.

Specific tool analyses:

-

PaP: Kaplan-Meier curves for PaP risk groups were plotted, and median survival for each group was determined to assess alignment with predicted ranges. Observed 30-day mortality proportions per risk group were compared to PaP and clinician predictions. C-statistic was calculated using risk group midpoint probabilities (85%, 50%, 15%).

-

FPN: Harrell’s C-index and calibration slope were calculated. Predicted and observed survival probabilities at 15, 30, and 60 days were compared, alongside clinician predictions.

-

PPI: McNemar’s test compared the accuracy of PPI and clinician predictions against observed deaths at 3 and 6 weeks. C-statistics were calculated for 3-week and 6-week predictions. Kaplan-Meier curves for PPI risk groups were plotted.

-

PPS: Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted for each PPS level to assess discrimination. Clinician ability to categorize patients into iso-prognostic groups (10% 30-day survival probability increments) was similarly evaluated. PPS C-statistic was calculated by comparing performance to published 30-day survival probabilities for PPS categories [30].

III. Results

A total of 1833 participants (1610 with capacity, 223 without) were enrolled. Median survival from enrollment was 45 days (IQR 16-140). Participant characteristics are detailed in Table 2.

A. Participant Characteristics

Table 2 summarizes participant demographics, cancer types, metastatic sites, treatment status, symptom prevalence, clinical assessments, performance scores (ECOG, Karnofsky), global health status, and blood count/biochemistry results.

Table 2. Participant Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Age (years); mean (SD); n = 1832* | 70.2 (11.9) |

| Gender; n (%); n = 1832* | |

| Male | 938 (51.2) |

| Female | 894 (48.8) |

| Location; n (%) | |

| Inpatient Palliative Care Unit | 1241 (67.7) |

| Community Palliative Care Team | 468 (25.5) |

| Hospital Palliative Care Team | 124 (6.8) |

| Site of Primary Tumor**; n (%) | |

| Lung | 362 (19.8) |

| Upper GI Tract | 337 (18.4) |

| Head and Neck | 280 (15.3) |

| Prostate | 160 (8.7) |

| Breast | 146 (8.0) |

| Gynecological | 133 (7.3) |

| Other | 123 (6.7) |

| Urological (bladder, testes, renal) | 112 (6.1) |

| Lower GI Tract | 81 (4.4) |

| Hematological | 70 (3.8) |

| Unknown | 45 (2.5) |

| Neurological | 38 (2.1) |

| Rare Tumor | 27 (1.5) |

| Site of Metastatic Disease; n (%) | |

| Bone | 555 (30.3) |

| Liver | 538 (29.4) |

| Nodal | 516 (28.2) |

| Lung | 477 (26.0) |

| Other | 353 (19.3) |

| None | 279 (15.2) |

| Brain | 134 (7.3) |

| Pleural Effusion | 98 (5.4) |

| Ascites | 95 (5.2) |

| Adrenal | 79 (4.3) |

| Unknown | 60 (3.3) |

| Skin | 36 (2.0) |

| Renal | 20 (1.1) |

| Currently Receiving Tumor Therapy; yes n (%) | 391 (21.3) |

| If yes, type of therapy: | |

| Chemotherapy | 190 (48.6) |

| Radiotherapy | 118 (30.2) |

| Hormone Therapy | 76 (19.4) |

| Other Tumor Directed Therapy (e.g., immunotherapy) | 42 (10.7) |

| Capacity to Consent; n (%) | 1610 (87.8) |

| Time Between Diagnosis and Date Became Incurable; n = 1821 | |

| Mean (SD); months | 13.2 (32.8) |

| Median (IQ Range); months | 0 (0, 12) |

| Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS); n = 1826 | |

| Less than 4 | 208 (11.4) |

| Greater or Equal to 4 | 1618 (88.6) |

| Presence or Absence of Key Symptoms | |

| Anorexia; yes; n = 1830 | 968 (52.9) |

| Dysphagia; yes; n = 1830 | 554 (30.3) |

| Dyspnea; yes; n = 1831 | 652 (35.6) |

| Fatigue; yes; n = 1831 | 1617 (88.3) |

| Lost Weight; yes; n = 1831 | 1194 (65.2) |

| Clinical Assessments | |

| Ascites; n = 1830 | 245 (13.4) |

| Presence of Peripheral Edema; n = 1831 | 685 (37.4) |

| Pulse Rate; beats/min; mean (SD); n = 1817 | 82.2 (14.7) |

| Presence of Delirium; n = 1830 | 66 (3.6) |

| If Yes, is it considered to be caused by a single medication | 2 (3.0) |

| Oral Intake; n = 1830 | |

| Normal | 587 (32.1) |

| Moderately Reduced | 666 (36.4) |

| Severely Reduced | 577 (31.5) |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score (ECOG) Performance status; n = 1831 | |

| Grade 0 | 15 (0.8) |

| Grade 1 | 202 (11.0) |

| Grade 2 | 520 (28.4) |

| Grade 3 | 822 (44.9) |

| Grade 4 | 272 (14.9) |

| Global Health Status (overall health); n (%); n = 1823 | |

| 1 (Very poor) | 144 (7.9) |

| 2 | 414 (22.7) |

| 3 | 680 (37.3) |

| 4 | 348 (19.1) |

| 5 | 180 (9.9) |

| 6 | 49 (2.7) |

| 7 (Excellent) | 8 (0.4) |

| Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS); n (%); n = 1830 | |

| 10 | 63 (3.4) |

| 20 | 108 (5.9) |

| 30 | 136 (7.4) |

| 40 | 229 (12.5) |

| 50 | 465 (25.4) |

| 60 | 404 (22.1) |

| 70 | 276 (15.1) |

| 80 | 114 (6.2) |

| 90 | 33 (1.8) |

| 100 | 2 (0.1) |

| Full Blood Count | Mean (SD) |

| White blood count (x109/L); n = 1602 | 11.3 (11.2) |

| Lymphocyte count (x109/L); n = 1596 | 1.2 (2.0) |

| Neutrophil count (x109/L); n = 1600 | 8.8 (6.2) |

| Platelets (x109/L); n = 1601 | 312.9 (147.6) |

| Biochemistry | |

| Urea (mmol/L); n = 1601 | 8.0 (6.4) |

| Albumin (g/L); n = 1600 | 30.1 (7.0) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L); n = 1587 | 231.7 (319.9) |

| Alanine transaminase (U/L); n = 1581 | 33.3 (71.7) |

| C reactive protein (mg/L); n = 1565 | 68.6 (73.5) |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (mmol/L); n = 1467 | 505.4 (446.0) |

* One participant preferred not to say.

** 73 participants had more than one primary tumor.

B. Clinician Characteristics

Analysis of clinician demographics indicated that most doctors were palliative care specialists (86%). Doctors had an average of 12.8 years of post-qualification experience and 6.2 years of palliative care experience. Nurses were almost exclusively palliative care nurses (98%), with a mean of 19.4 years post-qualification experience and 8.5 years in palliative care.

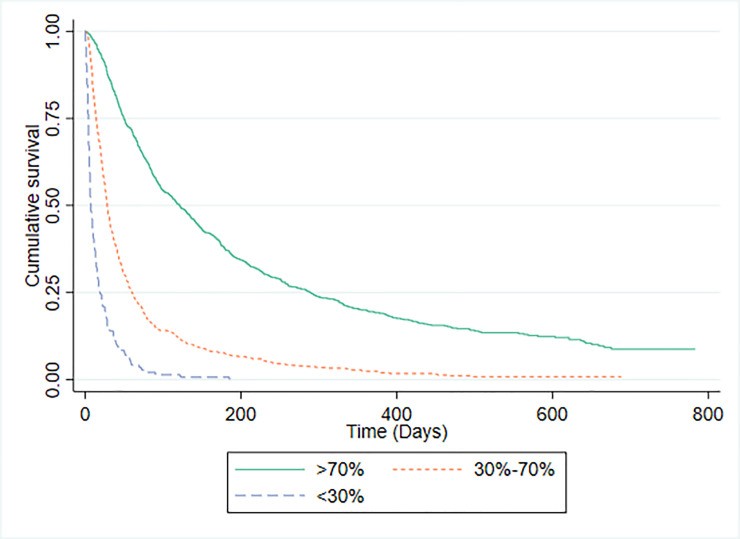

C. Palliative Prognostic (PaP) Score Performance

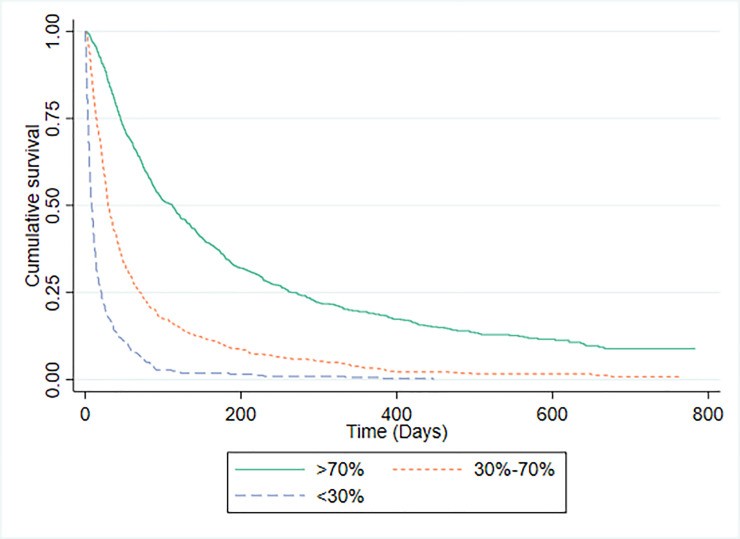

PaP scores were available for 1592 patients. The PaP model demonstrated a C-statistic of 0.771 (95% CI 0.749-0.792). Risk group distribution was: Group A (predicted >70% 30-day survival) 49.1%, Group B (30-70% probability) 41.1%, and Group C (<30% probability) 9.0%. Median survival times and observed 30-day survival proportions for each PaP risk group are shown in Fig 1. For comparison, Fig 2 presents Kaplan-Meier curves and survival data for patients categorized by CPS risk groups using the same probability thresholds as PaP. PaP and CPS exhibited comparable ability to categorize patients by 30-day mortality risk.

Fig 1. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves for PaP Risk Groups

Fig 2. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves According to CPS

D. Feliu Prognostic Nomogram (FPN) Performance

FPN’s Harrell’s C-index was 0.684 (95% CI: 0.669-0.700; n = 1432), indicating moderate discrimination. The calibration slope was 1.049 (95% CI: 0.939-1.158), demonstrating good calibration. FPN and CPS predicted similar probabilities of 15-day survival, both consistent with the observed 15-day survival rate. While FPN’s predicted 30 and 60-day survival probabilities were slightly lower than CPS predictions and observed survival, the differences were not statistically significant. FPN performed comparably to CPS in stratifying patients by 15, 30, and 60-day mortality risk.

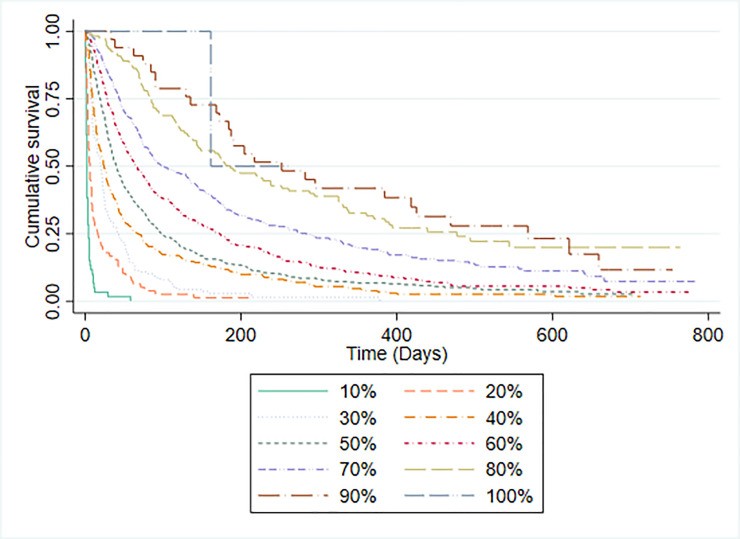

E. Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) Performance

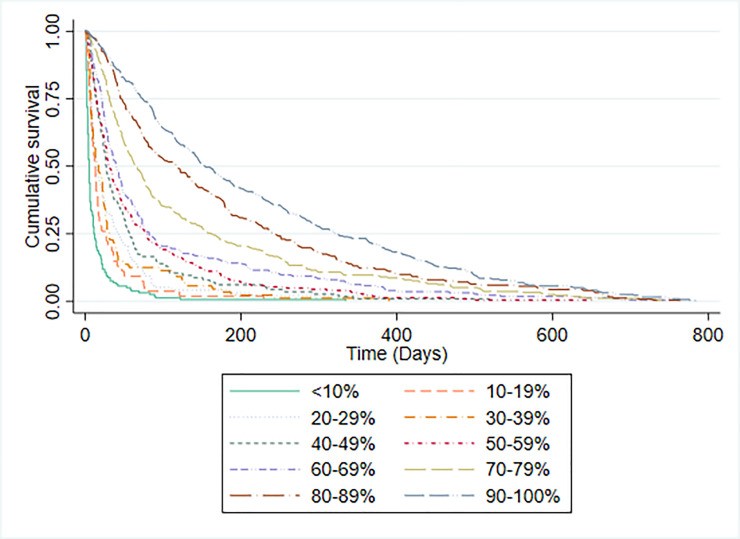

Table 3 displays PPS scores and median survival times. PPS demonstrated a C-statistic of 0.757 (95% CI 0.735-0.778). Kaplan-Meier curves for each PPS level (Fig 3) showed increasing median survival with better PPS scores, except for PPS 100% due to limited sample size. Fig 4 illustrates Kaplan-Meier curves for patients stratified by CPS-predicted 30-day survival probabilities. PPS and CPS showed similar ability to differentiate patient groups with varying prognoses.

Table 3. Participant Number and Median Survival Time by PPS Category

| PPS Score | n (%) | Median Survival Time (Days) (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | 60 (3.3) | 2 (1-4) |

| 20% | 78 (4.3) | 6 (3-16) |

| 30% | 138 (7.6) | 20 (7-42) |

| 40% | 273 (14.9) | 24 (10-69) |

| 50% | 493 (27.0) | 40 (19-97) |

| 60% | 376 (20.6) | 65 (28-172) |

| 70% | 265 (14.5) | 99 (44-284) |

| 80% | 109 (6.0) | 186 (85-477) |

| 90% | 33 (1.8) | 252 (135-568) |

| 100% | 2 (0.1)* | – |

*Too few participants for reliable survival time estimation.

Fig 3. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves by PPS Level

Fig 4. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves by 30-day CPS

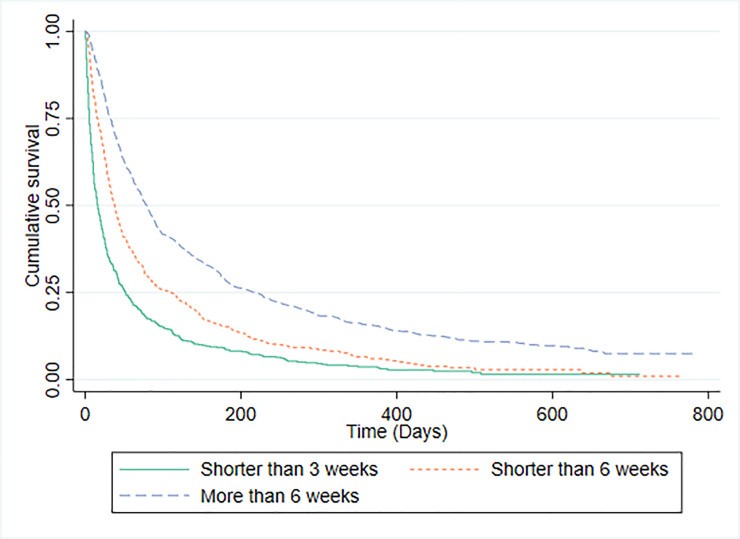

F. Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI) Performance

PPI stratified patients into three risk groups. Fig 5 shows Kaplan-Meier curves for these groups. C-statistics were 0.675 (0.652-0.699) for predicting survival <3 weeks and 0.655 (0.633-0.676) for survival >6 weeks. Median survival times for PPI risk groups are presented alongside Kaplan-Meier curves. Table 4 compares PPI and CPS prediction accuracy against observed survival. CPS correctly predicted outcomes more frequently (62.5%) than PPI (54.2%), a statistically significant difference (p<0.001). PPI was found to be statistically inferior to CPS in predicting 3-week and 6-week survival.

Fig 5. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves for PPI Predictions

Table 4. Accuracy Comparison: PPI vs. CPS Predictions

| Doctors’ Predictions Compared to Observed Deaths | |

|---|---|

| PPI Predictions Compared to Observed Deaths | CPS was Correct |

| PPI Prediction was Correct | 745 (40.8%) |

| PPI Prediction was Incorrect | 398 (21.8%) |

| Total | 1143 |

IV. Discussion

This study benchmarked the performance of four commonly used palliative care prognostic tools against clinical predictions of survival (CPS). While previous research has statistically validated these tools based on discrimination, calibration, and accuracy [23-25, 30-33], this study prioritized CPS as the clinical standard for comparison, reflecting real-world palliative care practice.

Our findings indicate that clinicians are as proficient as the PaP score in stratifying patients into 30-day survival risk groups. Similarly, CPS matched FPN’s ability to categorize patients by 15, 30, and 60-day survival probabilities. Although CPS showed slightly better accuracy than FPN at 30 and 60 days, this difference wasn’t statistically significant. Notably, PPI was significantly less accurate than CPS in predicting 3-week and 6-week survival. PPS and CPS demonstrated comparable capacity to sort patients into iso-prognostic groups, though direct comparison was limited by PPS’s design as a functional, not prognostic, tool.

Methodological challenges inherent in directly comparing prognostic models to CPS [16, 18, 34] represent a study limitation. For instance, PaP’s risk categories, while validated by our findings, offer probability ranges rather than definitive survival predictions. Clinicians demonstrated equivalent ability to discern these probability-based risk groups, questioning the added prognostic value of PaP in terms of accuracy alone.

Simplifying PaP to a continuous variable for easier comparison with temporal CPS predictions, as done in some studies [18, 34-36], may overlook the clinical application of PaP’s risk categories. The clinical utility of categorizing a patient into a 30-70% 30-day survival probability group remains ambiguous, as both survival and death within 30 days are plausible outcomes. Furthermore, the clinical relevance of PaP’s specific risk categories for patients, carers, and clinicians is debatable. Patient preference studies often reveal a aversion to statistical probabilities in prognostic information [37, 38], with general categories like days, weeks, or months being preferred [21].

FPN, included for its prior comparative evaluations [25], lacked independent validation post-publication. Our study validates its initial findings of acceptable discrimination and calibration. While FPN mirrored CPS in risk stratification across multiple time points, its discriminatory ability was lower than PiPS-A and PiPS-B models [21].

PPS, while not designed as a prognostic tool, demonstrated prognostic utility in a large retrospective analysis [30]. Our findings corroborate PPS’s ability to differentiate survival prospects, although median survival times per PPS category differed from prior reports. CPS also effectively stratified patients into iso-prognostic groups, mirroring PPS’s performance in this regard.

PPI, designed to predict 3-week and 6-week survival [22], has shown good performance in prior studies [17, 32, 39, 40]. However, our study revealed CPS to be significantly more accurate than PPI in predicting survival at these time points. While PPI aims for short-term predictions, its performance has been assessed at various time points beyond its intended scope [16, 17, 34, 36, 41], potentially misrepresenting its clinical utility.

Despite the lack of evidence suggesting superiority of these palliative care prognostic tools over CPS in terms of accuracy, their adoption in clinical practice may still hold value. Prognostic tools can offer objectivity and reproducibility, potentially serving as educational aids for less experienced clinicians, providing a second opinion, or standardizing prognostic assessments. Clinicians often find prognosticating challenging and may avoid explicit discussions of timescales. Objective tools could facilitate these difficult conversations and improve communication. Furthermore, these tools may enhance consistency in clinical trial enrollment criteria and service case-mix descriptions. Future research should prioritize evaluating the impact of palliative care prognostic tools and CPS on clinical decision-making, exploring their potential benefits beyond mere prognostic accuracy, such as ease of use, reliability, and objectivity.

V. Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the UCL PRIMENT Clinical Trials Unit, Karolina Christodoulides, Jane Harrington, Florence Todd-Fordham, the PiPS2 Investigators listed, the Study Steering Committee members (Professor Miriam Johnson, Dr Susan Charman, Angela McCullagh), and, most importantly, all participating patients, carers, and clinicians.

VI. Data Availability

Data will be publicly available from the UCL Research Data Repository (RDR) post-manuscript acceptance.

VII. Funding Statement

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (NIHR-HTA 13/20/01). The funders and sponsor had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, publication decisions, or manuscript preparation.

VIII. References

[List of references as in the original article]

IX. Associated Data

Data Availability Statement: All data files supporting conclusions of this study files will be publically available from the UCL Research Data Repository (RDR) after acceptance of the manuscript.