Introduction

The growing recognition of palliative care’s crucial role in enhancing the quality of life for individuals facing serious illnesses is undeniable. Evidence consistently demonstrates that integrating specialist palliative care improves patient well-being, the dying process, and bereavement experiences. Furthermore, it addresses broader societal concerns, such as the overuse of ineffective medical interventions and the underutilization of quality-of-life-promoting interventions like timely hospice referrals. However, a significant challenge persists: a nationwide shortage of palliative care specialists in the United States compared to the increasing population of patients with serious and life-threatening conditions. As healthcare systems evolve with a stronger emphasis on patient-centered care and cost-effectiveness, enhancing palliative care service delivery becomes paramount. A key component of this enhancement is improving the palliative care competency training of generalist physicians.

The feasibility of teaching palliative care competencies across various educational levels—undergraduate, graduate, and practicing physician—is well-established. Despite this progress, inconsistencies plague existing curricula and instructional methods across academic institutions. The absence of national standards for palliative care education in medical schools and residency programs necessitates urgent attention. Drawing parallels with other medical fields like geriatrics, pulmonary and critical care medicine, and emergency medicine, which have successfully established specialty-based consensus competencies, this study aims to define palliative care competencies for medical students and internal medicine and family medicine (IM/FM) residents.

This research builds upon a decade of dedicated effort in defining consensus-based clinical palliative care competencies and standardizing required competencies for hospice and palliative medicine (HPM) fellowships. The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care published clinical guidelines in 2004, followed by the National Quality Forum’s release of preferred practices in 2007. Simultaneously, in alignment with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)’s Outcome Project mandate for competency-based curriculum and assessment, academic palliative care leaders initiated a review process to develop comprehensive HPM fellowship competencies. These fellowship competencies, along with competency-based measurable outcomes and assessment methods, have since been endorsed by the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM).

Method

This study leveraged medical student and resident competencies derived from published HPM fellowship competencies as the foundation for a national survey. The survey aimed to assess content validity, prioritize essential graduation competencies, and rank the importance of palliative care domains for each learner group.

Drafting Proposed Competencies

In April 2010, a dedicated Medical Student and IM/FM Residency Competencies Workgroup was formed, comprising palliative care educators from six academic medical centers across the United States and a senior leader. The workgroup employed a multi-step process to generate comprehensive competency lists for medical students and residents, using HPM fellowship competencies as a starting point. First, two workgroup members reviewed each fellowship competency, categorizing it as a general medicine competency, a fellowship-level competency beyond generalist practice, or a fellowship-level competency adaptable for residents and medical students. From April 2010 to March 2011, the workgroup iteratively reviewed and revised competencies in the third category, deriving developmentally appropriate competencies for medical students and IM/FM residents through emails, conference calls, and in-person meetings. The language was kept consistent with fellowship competencies and crafted to be “SMART” (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timely). The resulting 18 medical student and 18 resident competencies were organized into five domains: pain and symptom management; communication; psychosocial, spiritual, and cultural aspects of care; terminal care and bereavement; and palliative care principles and practice. These were presented in a side-by-side table to emphasize the developmental progression across undergraduate and graduate training.

Survey Design and Implementation

A web-based survey using Qualtrics was developed to assess experts’ ratings and rankings of the proposed competencies and domains. The survey randomized the presentation order of the five domains and the items within each domain to minimize order bias. Confidentiality was ensured through survey instructions detailing data de-identification and secure storage. The study received approval from the Partners Institutional Review Board and met institutional review board requirements for each participating institution.

Respondents rated each competency at each training level as “essential for all,” “important for all,” “important for some,” or “not appropriate for this level,” with a limit of 10 competencies per learner group as “essential for all.” A running tally aided this process. “Essential for all” was defined as a prerequisite for graduation. Respondents were provided with a reference table comparing medical student and resident competencies by domain. To assess content validity, respondents could suggest revisions or additional competencies.

Finally, respondents weighted the importance of each of the five domains for each learner group, with the survey program ensuring the sum did not exceed 100%. Demographic information collected included gender, years in palliative care practice, palliative care practice proportion, board certification, faculty appointment, and teaching experience. Potential participants were notified and invited via email with a survey link. Reminder emails were sent over three weeks in February 2012. No incentives were offered.

Survey Participant Selection Process

Ninety-eight expert palliative care physician educators were identified based on three inclusion criteria:

-

Leadership in medical student or resident education: Leaders of palliative care programs or courses, curriculum/assessment tool developers, and faculty members with at least two years of teaching experience. Forty-nine educators were identified through AAHPM Fellowship Director listserv, Medical School Palliative Care Education project scholars, and AAHPM Leadership Education and Academic Development (LEAD) program participants.

-

Publications in medical student and IM/FM resident palliative care education: First or last author of one publication with HPM board certification, or two or more publications as first or last author with any board certification. A PubMed search using keywords “palliative care” and “medical education, undergraduate and graduate” (1996-present) and board certification verification identified 32 potential participants.

-

National leadership role and significant teaching experience: Leaders of national palliative care programs, participants in national medical education projects/committees, and those with over five years of medical student/resident teaching experience. Seventy-three participants met this criterion.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed, reporting frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. A competency was classified as required if ≥50% of experts rated it “essential for all” and ≤5% rated it “not appropriate.” Repeated-measures multivariate analysis of variance with contrasts assessed within-group differences across competency ratings/domains and between-group differences by faculty rank, with a significance level of α=0.05. SAS/STAT Version 9.3 (SAS Inc., 2012) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

The survey achieved a 72% response rate (71/98). Respondent demographics are detailed in Table 1. The majority reported dedicating most of their clinical time to palliative care, with representation from both junior and senior faculty, and extensive teaching experience across learner groups. Most respondents (93%) were board certified in HPM at the time of data collection.

Table 1. Characteristics of 71 Palliative Care Experts Participating in the Essential Competencies Survey, 2012

| Characteristic | Measure |

|---|---|

| Female gender, no. (%) | 36 (50.7) |

| Academic rank, no. (%) | |

| Instructor | 6 (8.4) |

| Assistant professor | 27 (38.0) |

| Associate professor | 22 (31.0) |

| Professor | 16 (22.5) |

| Proportion of current practice in palliative care, no. (%) | |

| 75–100% | 51 (71.8) |

| 50–74% | 10 (14.1) |

| 25–49% | 7 (9.8) |

| 0–24% | 3 (4.2) |

| Years in practice, mean (SD) | 11.7 (6.6) |

| Have taught for more than 5 years, no. (%) | |

| Medical students | 53 (79.1) |

| IM/FM residents | 49 (74.2) |

| Other residents | 44 (74.6) |

| Fellows | 47 (72.3) |

| Faculty | 50 (76.9) |

| Board certified in palliative care, no. (%) | 66 (93.0) |

| Primary board specialty, no. | |

| Internal medicine | 56 |

| Family medicine | 7 |

| Pediatrics | 4 |

| Geriatrics | 4 |

| Surgery, emergency medicine, medical oncology | 3 |

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation; IM = internal medicine; FM = family medicine.

Rating of Specific Competencies

The comprehensive and essential palliative care competencies are detailed in Supplemental Digital Appendix 1.

Medical Student Competencies

Table 2 reveals that most respondents rated all 18 medical student competencies as either “essential for all” or “important for all.” Seven competencies, spanning all five domains, were identified as essential by ≥50% of respondents. Few items were rated “not appropriate,” with no more than four respondents giving this rating to any single competency. Four respondents suggested additional items, but these were deemed not meaningfully different from the existing competencies. The top-ranked medical student competency was describing ethical principles in end-of-life decision-making. Communication and palliative care principles were also highly ranked, including using patient-centered techniques for bad news and resuscitation discussions, exploring patient/family understanding, self-reflection, defining palliative care/hospice roles, identifying psychosocial distress, and systematic pain assessment.

Table 2. Palliative Care Competencies for Graduating Medical Students, 2012

| Competency | Essential for all, no. (%) | Important for all, no. (%) | Important for some, no. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Describes ethical principles that inform decision-making in serious illness, including the right to forgo or withdraw life-sustaining treatment and the rationale for obtaining a surrogate decision maker. (TCB)b | 48 (67.6) | 21 (29.6) | 2 (2.8) |

| 2. Reflects on personal emotional reactions to patients’ dying and deaths. (PCPP)b | 40 (58.0) | 25 (36.2) | 4 (5.8) |

| 3. Identifies psychosocial distress in patients and families. (PSC)b | 40 (57.1) | 25 (35.7) | 5 (7.1) |

| 4. Explores patient and family understanding of illness, concerns, goals, and values that inform the plan of care. (C)b | 39 (57.3) | 25 (36.8) | 4 (5.9) |

| 5. Defines the philosophy and role of palliative care across the life cycle and differentiates hospice from palliative care. (PCPP)b | 37 (53.6) | 30 (43.5)) | 2 (2.9) |

| 6. Demonstrates patient-centered communication techniques when giving bad news and discussing resuscitation preferences. (C)b | 36 (56.2) | 24 (37.5) | 4 (6.2) |

| 7. Assesses pain systematically and distinguishes nociceptive from neuropathic pain syndromes. (PSM)b | 35 (50.0) | 31 (44.3) | 4 (5.7) |

| 8. Describes key issues and principles of pain management with opioids, including equianalgesic dosing, common side effects, addiction, tolerance, and dependence. | 33 (47.1) | 30 (42.9) | 7 (10.0) |

| 9. Demonstrates basic approaches to handling emotion in patients and families facing serious illness. | 32 (46.4) | 32 (46.4) | 5 (7.2) |

| 10. Identifies common signs of the dying process and describes treatments for common symptoms at the end of life. | 28 (39.4) | 28 (39.4) | 15 (21.1) |

| 11. Identifies patients’ and families’ cultural values, beliefs, and practices related to serious illness and end-of-life care. | 24 (34.8) | 39 (56.5) | 6 (8.7) |

| 12. Describes disease trajectories for common serious illnesses in adult and pediatric populations. | 22 (32.8) | 34 (50.7) | 11 (16.4) |

| 13. Describes the communication tasks of a physician when a patient dies, such as pronouncement, family notification, and request for autopsy. | 21 (31.3) | 36 (53.7) | 10 (14.9) |

| 14. Describes an approach to the diagnosis of anxiety, depression, and delirium. | 19 (27.5) | 37 (53.6) | 13 (18.8) |

| 15. Assesses non-pain symptoms and outlines a differential diagnosis, initial work-up and treatment plan. | 18 (25.7) | 41 (58.6) | 11 (15.7) |

| 16. Identifies spiritual and existential suffering in patients and families. | 12 (18.2) | 41 (62.1) | 13 (19.7) |

| 17. Describes the roles of members of an interdisciplinary palliative care team, including nurses, social workers, case managers, chaplains, and pharmacists. | 9 (13.8) | 36 (55.4) | 20 (30.8) |

| 18. Describes normal grief and bereavement, and risk factors for prolonged grief disorder. | 7 (10.8) | 38 (58.5) | 20 (30.8) |

Abbreviations: C = communication; PSM = pain and symptom management; PCPP= palliative care principles and practice; PSC = psychosocial, spiritual, and cultural aspects of care; TCB = terminal care and bereavement.

Resident Competencies

Table 3 presents the competencies for graduating IM/FM residents. Similar to medical student competencies, most respondents rated each resident competency as “essential for all” or “important for all.” No competency was deemed inappropriate, and no additional items were suggested. Thirteen competencies were identified as essential by ≥50% of respondents, representing all five domains. The top two resident competencies focused on patient-centered communication and shared decision-making. Terminal care and bereavement domain also featured prominently. Notably, seven of the essential resident competencies were advanced versions of essential medical student competencies. Other essential resident competencies included detailed opioid expertise, psychiatric symptom diagnosis and management, handling strong emotions, integrating cultural values, end-of-life symptom management, and post-death family communication.

Table 3. Palliative Care Competencies for Graduating Residents, 2012

| Competency | Essential for all, no. (%) | Important for all, no. (%) | Important for some, no. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Explores patient and family understanding of illness, concerns, goals, and values, and identifies treatment plans that respect and align with these priorities. (C) b | 58 (84.0) | 11 (15.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| 2. Demonstrates effective patient-centered communication when giving bad news or prognostic information, discussing resuscitation preferences, and coaching patients through the dying process. (C)b | 54 (79.4) | 13 (19.1) | 1 (1.5) |

| 3. Assesses pain systematically and treats pain effectively with opioids, non-opioid analgesics, and non-pharmacologic interventions. (PSM)b | 52 (74.3) | 16 (22.9) | 2 (2.9) |

| 4. Defines and applies principles of opioid prescription, including equianalgesic dosing and common side effects, and demonstrates an understanding that appropriate use of opioids rarely leads to respiratory depression or addiction when treating cancer-related pain. (PSM)b | 52 (73.9) | 16 (22.9) | 2 (2.9) |

| 5. Defines and explains the philosophy and roles of palliative care and hospice, and appropriately refers patients. (PCPP)b | 51 (73.9) | 16 (23.)1 | 2 (2.9) |

| 6. Describes and performs communication tasks effectively at the time of death, including pronouncement, family notification and support, and request for autopsy. (TCB)b | 51 (72.9) | 18 (25.7) | 1 (1.4) |

| 7. Describes and applies ethical and legal principles that inform decision-making in serious illness, including: a) the right to forgo or withdraw life-sustaining treatment; b) decision-making capacity and substituted judgment; and c) physician-assisted death. (TCB)b | 50 (71.4) | 15 (21.4) | 5 (7.1) |

| 8. Identifies and manages common signs and symptoms at the end of life. (TCB)b | 43 (61.4) | 24 (34.3) | 3 (4.3) |

| 9. Evaluates psychological distress in individual patients and families, and provides support and appropriate referral. (PSC)b | 42 (60.0) | 26 (37.1) | 2 (2.9) |

| 10. Reflects on his or her own emotional reactions, models self-reflection, and acknowledges team distress when caring for dying patients and their families. (PCPP)b | 40 (58.0) | 27 (39.1) | 2 (2.9) |

| 11. Assesses and diagnoses anxiety, depression, and delirium and provides appropriate initial treatment and referral. (PSM)b | 39 (56.5) | 29 (42.0) | 10(1.4) |

| 12. Demonstrates effective approaches to exploring and handling strong emotions in patients and families facing serious illness. (C)b | 37 (54.4) | 30 (44.1) | 1 (1.5) |

| 13. Identifies patients’ and families’ values, cultural beliefs, and practices related to serious illness and end-of-life care, and integrates these into the care plan. (PSC)b | 35 (50.0) | 32 (45.7) | 3 (4.3) |

| 14. Assesses and manages non-pain symptoms and conditions including, but not limited to, dyspnea, nausea, bowel obstruction, and cord compression using current best practices. | 32 (45.7) | 34 (48.6) | 4 (5.7) |

| 15. Applies the evidence base and knowledge of disease trajectories to estimate prognosis in individual patients. | 26 (37.7) | 37 (53.6) | 6 (8.7) |

| 16. Identifies spiritual and existential distress in individual patients and families, and provides support and appropriate referral. | 18 (26.1) | 43 (62.3) | 8 (11.6) |

| 17. Describes the roles of and collaborates with members of an interdisciplinary care team when creating a palliative patient care plan. | 16 (23.2) | 44 (63.8) | 9 (13.0) |

| 18. Differentiates normal grief from prolonged grief disorder, and makes appropriate referrals. | 12 (17.6) | 45 (66.2) | 11 (16.2) |

Abbreviations: C = communication; PSM = pain and symptom management; PCPP= palliative care principles and practice; PSC = psychosocial, spiritual, and cultural aspects of care; TCB = terminal care and bereavement.

Ranking of Palliative Care Domains

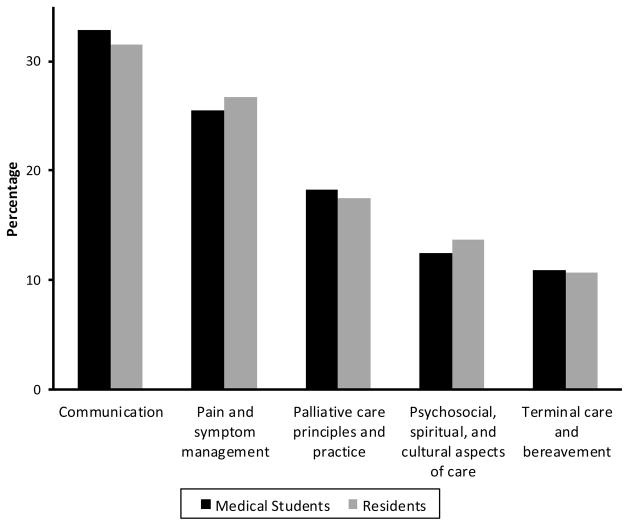

Figure 1 illustrates the relative weights assigned to each palliative care domain for both medical students and residents. Communication and pain/symptom management were consistently ranked highest for both groups. Domain ranking differences were statistically significant across all domains except between psychosocial care and terminal care.

Figure 1. Relative Importance of Palliative Care Competency Domains

Relative weight of importance of competencies assigned by 68 experts to each of five palliative care domains.

Discussion

This national survey of expert palliative care physician educators successfully defined comprehensive and essential palliative care competencies for medical students and IM/FM residents. These competencies offer a standardized framework for palliative care curricula content and assessment at both educational levels and can serve as a foundation for future research validating new assessment tools across all learner levels. Crafted to be specific, measurable, achievable, and relevant, these competencies align with existing ACGME competencies and standardized assessment tools used in HPM fellowship training. The developmental framework is also consistent with the ACGME’s New Accreditation System (NAS) mandate for “milestones,” or educational outcomes demonstrating learner progression from novice to expert competency levels. These competencies can be utilized to define reportable educational outcomes as residency programs meet new ACGME credentialing requirements.

The identified essential competencies also suggest a developmental sequence for palliative care education. Medical students must first establish an ethical foundation for caring for seriously ill patients and integrate these experiences into their physician identity. Residents then build upon this foundation, deepening their knowledge, skills, and attitudes. For instance, residents must not only understand palliative care but also appropriately refer patients to hospice, evaluate and refer patients with psychosocial distress, and model self-reflection for their teams. Essential resident competencies encompass more complex symptom management, patient-centered communication for goal clarification, and understanding hospice/palliative care within the healthcare system. Assessment approaches should reflect these developmental differences, such as using standardized patient simulations for medical student bad news delivery skills and 360° evaluations for resident communication competencies after family meetings.

Recognizing varied learner skill levels, these competencies should be applied flexibly, adapting to individual learning trajectories. While a second-year resident may achieve competency in some areas, all 13 essential competencies should be attained by residency completion. These competencies can also identify training gaps in medical education and continuing medical education for practicing physicians. Practicing internists, for example, should demonstrate all 13 essential competencies, guiding continuing medical education programs to address potential gaps.

This study underscores the critical need to consistently teach and reinforce patient-centered communication techniques and symptom management across all training levels. Patients facing serious illnesses prioritize physician communication and symptom management. Therefore, robust physician training in these and other fundamental palliative care competencies is crucial for developing and implementing patient-centered care models for seriously ill individuals.

Limitations of this study include the initial competency drafting primarily involving seven experts. However, the derivation from HPM fellowship competencies, widely vetted by expert educators, mitigates this. The 72% survey response rate and balanced demographics strengthen the generalizability of findings. While acknowledging the interdisciplinary team’s role in medical education, the survey focused on physician experts to define competencies for independent physician practice. Future steps include seeking broader medical education community input and endorsement to maximize impact and facilitate competency integration into medical training.

In conclusion, this study, through expert review and a national survey, defined comprehensive and essential generalist-level palliative care competencies for undergraduate and graduate medical education in internal medicine and family medicine. It is proposed that the academic medical community should elevate the standard, requiring all graduating medical students and IM/FM residents to demonstrate competency in the five palliative care domains. Early and developmentally sequenced competency introduction may enhance physicians’ clinical efficacy and, more importantly, improve care quality for patients with serious illnesses.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content: NIHMS584235-supplement-Supplemental_Digital_Content.pdf

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr. Periyakoil’s work was supported by NIH Grants RCA115562A and 1R25MD006857 and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Approved by the Partners Institutional Review Board and met institutional requirements.

Previous presentations: Data presented at AAHPM Annual Assembly 2012 and 19th International Congress on Palliative Care, 2012.

Contributor Information

Dr. Kristen G. Schaefer, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Eva H. Chittenden, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Amy M. Sullivan, The Academy at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Dr. Vyjeyanth S. Periyakoil, Stanford University School of Medicine and Veterans Administration Palo Alto Health Care System.

Dr. Laura J. Morrison, Yale University School of Medicine, Yale-New Haven Hospital.

Dr. Elise C. Carey, Mayo Clinic Rochester.

Dr. Sandra Sanchez-Reilly, Geriatric Research, Education Clinical Center, South Texas Veterans Health Care System and University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Dr. Susan D. Block, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School Center for Palliative Care, Harvard Medical School.

References

[References from the original article would be listed here]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content: NIHMS584235-supplement-Supplemental_Digital_Content.pdf