Early identification of patients who could benefit from palliative care in the emergency department (ED) is crucial. A proactive approach ensures that these individuals receive appropriate care aligned with their needs and preferences, avoiding unnecessary treatments and improving their overall experience. The Palliative Care and Rapid Emergency Screening (P-CaRES) tool emerges as a promising solution in this challenging clinical setting. This article delves into the effectiveness of the P-CaRES screening tool, particularly when used in conjunction with the Surprise Question (SQ), in predicting mortality and facilitating timely palliative care discussions for older adults in the ED.

Studies have consistently highlighted the value of screening tools in identifying patients with palliative care needs within the fast-paced environment of the emergency department. Our research, alongside findings from Paske et al., underscores the predictive power of the P-CaRES tool in assessing mortality risk. Paske and colleagues observed that a significant portion – 51.2% – of patients who screened positive using P-CaRES sadly passed away within six months of hospital discharge. This emphasizes the tool’s ability to flag individuals facing serious health challenges.

While Paske’s study evaluated patients approximately 26 hours post-admission, our investigation focused on real-time assessment within the ED itself. This immediate evaluation in the ED setting allows for the prompt establishment of care objectives. By identifying patients who might be approaching the end-of-life or who would benefit from palliative approaches, we can prevent the administration of treatments that may be burdensome rather than beneficial.

Furthermore, our work validates the P-CaRES tool’s utility in recognizing patients with pre-existing conditions. Intriguingly, we discovered that combining P-CaRES with easily obtainable triage vital signs – specifically elevated body temperature (BT > 37.5 °C), rapid pulse rate (PR > 100 bpm), and increased respiratory rate (RR > 25 bpm) – significantly enhances its predictive capability. This combined approach can serve as a robust method for emergency physicians to pinpoint older adults who would greatly benefit from serious illness conversations. These crucial discussions can pave the way for initiating palliative care either directly in the ED or shortly after admission, ensuring timely and compassionate care.

The P-CaRES tool’s strength lies in its consideration of potential terminal illnesses, recognizing conditions that, when coupled with abnormal vital signs indicative of acute exacerbation, can markedly increase mortality risk. The Surprise Question (SQ), phrased as “Would I be surprised if this patient died within [timeframe]?”, serves as a complementary assessment. Our findings regarding SQ (“No, I would not be surprised”) align with research by Nicola et al., who reported a 74.8% accuracy rate for SQ in mortality prediction.

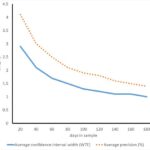

However, systematic reviews of screening tools, including SQ, in the ED context reveal nuances. While SQ may exhibit lower sensitivity for short-term (1-month) mortality prediction, its accuracy improves over longer periods (e.g., 12 months). Conversely, SQ demonstrates high specificity in the short-term but lower specificity in the long-term. Our results suggest that integrating SQ with other mortality predictors readily available at triage and in electronic medical records – such as the aforementioned vital signs and the presence of a palliative care plan – maximizes its predictive power, particularly for 3-month mortality. This enhanced SQ approach becomes a valuable asset in identifying older adults who would benefit from serious illness conversations and palliative care services within and beyond the emergency department.

Our study’s focus on 3-month survival prediction expands the existing body of knowledge concerning the Surprise Question’s association with mortality in the ED and broader patient populations. Notably, the strength of association we observed (Hazard Ratio: 7.73; 95% CI: 3.03–19.79) exceeded that reported in previous studies. This difference could stem from various factors influencing emergency physicians’ prognostic perceptions, including their clinical experience, patients’ underlying conditions, and the severity of acute medical presentations. It’s recognized that clinicians with greater experience often demonstrate superior accuracy in these assessments. Furthermore, variations in the acute care needs of ED patients and the availability of life-sustaining interventions might contribute to these discrepancies.

While broad and narrow criteria have been proposed to identify patients with pre-existing conditions in the ED who may warrant palliative care consideration, our study did not find that positive broad or narrow criteria directly correlated with decreased 3-month survival. This unexpected finding might be attributed to the inclusion of broad criteria employing the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The CCI, initially designed for 10-year survival prediction, may be less sensitive for capturing short-term mortality risks, as assessed in our 1-month and 3-month outcome analysis.

Clinical Implications for P-CaRES in Emergency Medicine

Our research robustly demonstrates that both the Surprise Question (“no surprise”) and a positive P-CaRES screening are significant predictors of mortality, particularly at 3 months. When P-CaRES is effectively combined with vital sign assessments, it provides a clinically useful tool for ED physicians. This combined approach can facilitate sensitive and timely discussions regarding care objectives with patients and their families. Looking ahead, future research should explore further enhancing prognostic accuracy by integrating vital signs with disease-specific prognostic tools relevant to conditions like dementia, COPD, or decompensated heart failure.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

It’s important to acknowledge the limitations inherent in our single-center study. The use of convenience sampling, dictated by research assistant and resident physician availability during weekday hours (8:00 AM to 4:00 PM), introduces potential selection bias. Moreover, the study period coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, and patients under investigation for COVID-19 were intentionally excluded, which could limit the generalizability of the findings to pandemic or post-pandemic contexts. Data collection relied on research assistants and junior physicians, and while inter-rater reliability for P-CaRES is known to be high and less subjective, formal intra-rater reliability assessment was not performed in our study. Finally, the relatively small sample size constrained our ability to conduct stratified analyses for specific diagnoses. Future research with larger, multi-center designs and broader patient populations is warranted to further validate and expand upon these findings, solidifying the role of the P-CaRES screening tool in optimizing palliative care delivery within the emergency department.