Integrated care is increasingly recognized as a vital strategy to address the complexities of modern healthcare systems. By fostering collaboration among diverse professionals and organizations, integrated care interventions aim to enhance patient experiences, improve care quality, and manage costs effectively [1]. However, the implementation of integrated care is not without its challenges. Despite its growing adoption, the success of integrated care interventions varies significantly, and the factors that contribute to successful implementation across different settings remain poorly understood [2**, 3**, 4]. Experts emphasize the need to adapt successful integrated care models and best practices to the unique context of each local environment [2**, 5**, 6]. Beyond considering broad societal factors like political, economic, and cultural landscapes [7], it is crucial for policymakers and healthcare leaders to understand and optimize the internal organizational context and collective capabilities of the entities responsible for implementing integrated care initiatives [2**, 8]. Research consistently highlights the importance of various organizational elements, including leadership styles, organizational culture, resource availability, information technology infrastructure, past experiences with change and innovation, organizational bureaucracy, dedication to quality improvement, and a patient-centric approach [9, 10, 11**, 12]. These contextual variations and capability differences may partially explain the inconsistent outcomes and performance levels observed in integrated care literature [8**, 13**].

The field of implementation science broadly defines “organizational context” as the specific setting where a proposed change is to be implemented [14], encompassing all factors external to the intervention itself [15]. In this article, we conceptualize contextual factors within organizations as “organizational capabilities.” This term emphasizes that these factors are not static organizational attributes but rather dynamic elements capable of development and refinement. We define “organizational capabilities” as an organization’s, or a group of organizations’, capacity to execute coordinated tasks that underpin integrated care delivery [16]. Many organizational capabilities, such as effective governance, visionary leadership, robust information technology, and strong inter-organizational partnerships, are widely acknowledged as crucial determinants of the success or failure of integrated care interventions [11**, 17, 18, 19]. However, current knowledge lacks specific insights into when and how these factors exert their influence across diverse settings [2**, 3]. This knowledge gap stems from the limited description and measurement of organizational capabilities in empirical studies of integrated care. Many evaluations of integrated care interventions provide only brief organizational descriptions, if any [e.g., 20**, 21**, 22], or focus solely on easily quantifiable variables like organizational age, size, and staff composition [23**, 24**, 25]. While some integrated care studies employ qualitative case study methods to offer more in-depth assessments of organizational capabilities [e.g., 26**, 27**], the specific capabilities examined vary, and a unified framework is absent.

Both quantitative and qualitative research on integrated care often prioritizes information technology, inter-professional teamwork, and partnerships, overlooking other crucial organizational factors such as resource allocation, leadership approaches, and internal readiness for change [e.g., 28**, 29]. Factors like information technology, inter-professional teamwork, and partnerships exist at the intersection of organizational capabilities and the integrated care intervention itself. They reflect the functionality of integrated care interventions and the degree of care integration achieved. This prevalent focus on assessing progress toward integrated care delivery, rather than the foundational organizational capabilities and conditions, is common in integrated care research. However, persistent challenges in implementing integrated care [e.g., 11, 27, 30] and expert consensus on the importance of tailoring interventions to the local organizational and environmental context [5**, 6] underscore the value of focusing on understanding and optimizing organizational capabilities for successful integration. Without a clear understanding of the organizational capabilities that support integrated care, researchers face difficulties in generalizing findings and best practices across different contexts, and healthcare leaders and providers may encounter unforeseen obstacles in their efforts to achieve integrated care.

This study aimed to develop and validate a comprehensive conceptual framework of organizational capabilities for integrated care and to explore the mechanisms through which these capabilities influence integrated care initiatives. The specific objectives were:

- To identify and describe organizational and inter-organizational capabilities that influence the implementation, management, and sustainability of integrated care interventions.

- To propose a conceptual framework that organizes these factors and captures their key relationships.

- To validate the framework and prioritize the most critical organizational capabilities based on the experiences of key stakeholders involved in integrated care.

Understanding Organizational Change in Integrated Care

What is Integrated Care and Why Organizational Change is Crucial

Integrated care represents a paradigm shift in healthcare delivery, moving away from fragmented, siloed services towards a more coordinated and patient-centered approach. At its core, integrated care seeks to link various aspects of health and social care services to provide seamless, comprehensive, and efficient care. This often involves bringing together different professionals, organizations, sectors, and even funding streams to work collaboratively towards shared goals focused on the needs of individuals and communities.

The inherent nature of integrated care necessitates significant organizational change. It’s not simply about adding a new program or service; it requires fundamental shifts in how healthcare organizations operate, interact, and deliver care. These changes can span across multiple dimensions:

- Structural Changes: Reorganizing departments, creating new roles and teams, establishing new governance structures, and altering reporting lines to facilitate better coordination and communication across different parts of the organization or network.

- Process Changes: Redesigning care pathways, developing shared protocols and guidelines, implementing new information sharing systems, and establishing collaborative decision-making processes to ensure smooth transitions and coordinated care delivery.

- Cultural Changes: Fostering a culture of collaboration, shared responsibility, patient-centeredness, and continuous learning. This involves shifting mindsets, values, and behaviors at all levels of the organization to embrace integrated care principles.

These organizational changes are essential for realizing the full potential of integrated care. Without effectively managing these changes, integrated care initiatives can falter, failing to achieve their intended goals of improved quality, enhanced patient experience, and cost-effectiveness. The right organizational change tools and strategies are therefore critical for navigating the complexities of implementing and sustaining integrated care.

The Challenge of Organizational Context

Implementing integrated care is rarely a straightforward, linear process. Healthcare organizations operate within complex and dynamic environments, each with its own unique set of characteristics, challenges, and opportunities. This “organizational context” significantly influences the implementation and success of any change effort, including integrated care.

The concept of organizational context is multifaceted, encompassing a wide array of internal and external factors that can shape how change unfolds. These factors can act as enablers, facilitators, or barriers to integrated care implementation. Understanding and addressing the nuances of organizational context is crucial for tailoring change strategies and maximizing the likelihood of success.

Key dimensions of organizational context relevant to integrated care include:

- Internal Context:

- Organizational Culture: The shared values, beliefs, and norms that shape behavior and decision-making within the organization. A culture that values collaboration, innovation, and patient-centeredness is more conducive to integrated care.

- Leadership: The style, vision, and commitment of leaders play a critical role in driving and supporting change. Effective leadership can inspire staff, build buy-in, and provide the necessary resources and direction for integrated care initiatives.

- Resources: The availability of financial, human, technological, and informational resources is essential for implementing and sustaining changes. Resource constraints can significantly hinder progress.

- Structure and Design: The organizational hierarchy, communication channels, and decision-making processes can either facilitate or impede coordination and collaboration required for integrated care.

- Readiness for Change: The collective willingness and ability of the organization and its members to embrace and adapt to change. Resistance to change can be a major obstacle.

- Existing Capabilities and Experiences: Past experiences with change initiatives, existing levels of collaboration, and the organization’s inherent capabilities in areas like IT, quality improvement, and partnership development can influence the trajectory of integrated care implementation.

- External Context:

- Policy and Regulatory Environment: Government policies, regulations, and funding models can either support or hinder integrated care efforts.

- Community Needs and Demographics: The specific health and social needs of the community being served, as well as demographic factors, influence the type and design of integrated care interventions.

- Inter-organizational Relationships: The nature of relationships with other healthcare and social care organizations in the local system – whether collaborative or competitive – impacts the potential for partnership and system-level integration.

- Economic and Social Conditions: Broader economic trends and social determinants of health in the community can influence both the need for and the feasibility of integrated care initiatives.

Ignoring these contextual factors can lead to mismatches between the intended integrated care intervention and the organizational realities, resulting in implementation challenges, limited impact, and even project failure. Therefore, Organizational Change Tools For Integrated Care must be context-sensitive and adaptable to the specific circumstances of each organization and setting.

Defining Organizational Capabilities for Integrated Care

To effectively navigate the complexities of organizational context, it’s helpful to focus on “organizational capabilities.” This concept shifts the perspective from viewing context as a static backdrop to understanding it as a dynamic set of internal capacities that organizations can develop and leverage to achieve their goals, particularly in the realm of integrated care.

Organizational capabilities, in this context, are defined as the organization’s (or network of organizations’) ability to perform coordinated sets of tasks that support the delivery of integrated care. This definition emphasizes several key aspects:

- Dynamic Nature: Capabilities are not fixed traits but rather evolve over time through learning, experience, and deliberate development efforts. Organizations can actively build and strengthen their capabilities.

- Action-Oriented: Capabilities are about “doing” – the ability to execute specific tasks and activities effectively. For integrated care, this includes capabilities related to collaboration, communication, care coordination, data sharing, and quality improvement.

- Coordinated and Integrated: The focus is on the coordinated performance of tasks. Integrated care requires different parts of the organization or network to work together seamlessly. Capabilities must enable this integration.

- Supportive of Integrated Care: The capabilities are specifically defined in relation to their contribution to integrated care delivery. They are the internal organizational assets that enable successful integration.

Organizational capabilities for integrated care encompass both tangible and intangible elements:

- Tangible Capabilities: These are the more concrete and readily observable resources and structures, such as:

- Financial Resources: Funding, budgets, and investment capacity to support integrated care initiatives.

- Human Resources: Skilled and dedicated staff, leadership expertise, and workforce capacity.

- Information Technology: Electronic health records, data sharing platforms, communication systems, and analytical tools.

- Physical Infrastructure: Facilities, equipment, and geographic locations that support integrated service delivery.

- Organizational Structure and Design: Formal organizational charts, reporting lines, and governance mechanisms.

- Intangible Capabilities: These are the less visible but equally important aspects, often related to organizational culture, knowledge, and relationships, such as:

- Leadership Capacity: Visionary leadership, change management skills, and the ability to foster collaboration.

- Organizational Culture: Values, norms, and beliefs that promote teamwork, patient-centeredness, and continuous learning.

- Knowledge and Expertise: Clinical knowledge, care coordination skills, project management expertise, and understanding of integrated care principles.

- Relational Capabilities: Trust, communication, and collaboration skills within and between organizations.

- Learning and Innovation Capacity: Ability to learn from experience, adapt to change, and implement new practices.

- Readiness for Change: Collective willingness and ability to embrace and implement change.

By focusing on developing and leveraging these organizational capabilities, healthcare organizations can equip themselves with the necessary tools to effectively implement and sustain integrated care, navigate the complexities of their context, and ultimately achieve better outcomes for patients and communities. The CCIC Framework, as discussed below, provides a structured approach to understanding and developing these critical capabilities.

The Context and Capabilities for Integrated Care (CCIC) Framework: A Toolkit for Change

The Context and Capabilities for Integrated Care (CCIC) Framework, developed through a rigorous literature review and validated by insights from healthcare leaders and providers, offers a comprehensive toolkit for understanding and enhancing organizational change in integrated care. This framework identifies key organizational capabilities and categorizes them into three interconnected domains, providing a structured approach to assess, develop, and leverage these capabilities for successful integrated care implementation.

Overview of the CCIC Framework

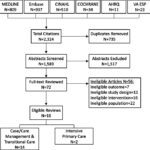

The CCIC Framework (Figure 1) posits that the success of integrated care interventions is significantly influenced by the organizational context and the capabilities that organizations possess or develop. It organizes eighteen distinct organizational capabilities across three broad categories:

- Basic Structures: These are the foundational elements that provide the infrastructure for integrated care. They include tangible resources and organizational design elements.

- People and Values: This category encompasses the human and cultural aspects that drive and shape organizational behavior and change. It focuses on leadership, culture, values, and readiness for change.

- Key Processes: These are the operational mechanisms and activities that enable the delivery and continuous improvement of integrated care. They include partnering, care delivery, performance measurement, and quality improvement processes.

These capabilities are not isolated but rather interconnected and interdependent. The framework emphasizes that these capabilities can be examined both at the individual organizational level and at the network level, recognizing that integrated care often involves collaboration across multiple organizations. Furthermore, the framework acknowledges the influence of external factors, represented by “Characteristics of the Integrated Care Intervention” and “Characteristics of the Patient Population,” which interact with organizational capabilities to shape outcomes.

The CCIC Framework serves as a valuable tool for:

- Assessment: Organizations can use the framework to assess their current capabilities for integrated care, identify strengths and weaknesses, and pinpoint areas for improvement.

- Planning: The framework can guide the planning and design of integrated care interventions by highlighting the organizational capabilities that need to be in place for successful implementation.

- Change Management: By understanding the key capabilities and their interrelationships, organizations can develop targeted change management strategies to build and strengthen the necessary capabilities.

- Evaluation: The framework provides a structure for evaluating the organizational context and capabilities that contribute to the success or failure of integrated care initiatives.

By providing a structured and comprehensive view of organizational capabilities, the CCIC Framework empowers healthcare leaders and researchers to move beyond generic notions of “organizational context” and delve into the specific tools and levers for driving successful organizational change in integrated care.

Basic Structures as Foundational Tools for Change

The “Basic Structures” domain of the CCIC Framework encompasses six organizational capabilities that provide the essential foundation for integrated care. These are the tangible elements and organizational design choices that create the necessary infrastructure for collaboration and coordinated care delivery. When strategically developed, these basic structures serve as powerful organizational change tools.

-

Physical Features: This capability refers to the structural and geographic characteristics of the organization or practice and the network. As a change tool, optimizing physical features can involve co-locating services, creating integrated care centers, or leveraging telehealth to overcome geographical barriers and improve access to integrated care. Examples include the size and age of facilities, urban or rural location, the layout of clinics to facilitate team-based care, and the geographic proximity of network partners to enable easier communication and collaboration.

-

Resources: This encompasses the availability of tangible and intangible assets for ongoing operations, both within individual organizations and for network activities. As a change tool, strategic resource allocation is critical. This includes securing adequate staffing, dedicated funding streams for integrated care initiatives, knowledge resources, project management support, and administrative capacity. Intangible resources like organizational reputation and brand can also be leveraged to build trust and attract partners.

-

Governance: This capability describes how the governing body (e.g., board or steering committee) is organized and its activities in directing, managing, and monitoring the organization or network. As a change tool, effective governance structures ensure clear decision-making processes, accountability mechanisms, and strategic direction for integrated care. This can involve establishing joint governance bodies for networks, defining clear roles and responsibilities for partners, and developing shared strategic plans. Examples include board composition, types of sub-committees, frequency of meetings, and the extent of centralized planning and standardization.

-

Accountability: This refers to the mechanisms in place to ensure that individuals and organizations meet formal expectations within the organization and across the network. As a change tool, well-defined accountability frameworks drive behavior change and ensure that integrated care goals are prioritized and achieved. This can include implementing performance-based contracts, establishing data sharing agreements with clear accountability for data privacy and security, and aligning organizational mandates to support integrated care. Examples include regulations, formal agreements, organizational mandates, and professional scopes of practice.

-

Information Technology: This capability focuses on the availability and usability of technology-based communication and information storage mechanisms within and across organizations. As a change tool, IT is a powerful enabler of integrated care. Implementing shared electronic health records, secure communication platforms, telehealth systems, and data analytics capabilities can significantly improve care coordination, information sharing, and decision-making. Examples include shared electronic medical records, email communication systems, video conferencing, data access and mining tools, and telehealth infrastructure.

-

Organizational/Network Design: This refers to the arrangement of units and roles and how they interact to accomplish tasks within the organization and across the network. As a change tool, redesigning organizational structures and workflows can break down silos and facilitate integrated care delivery. This can involve creating integrated care teams, establishing new care pathways that span across different departments or organizations, and defining clear communication and decision-making channels. Examples include organizational charts, departmental structures, job descriptions, and communication protocols.

By strategically developing and aligning these basic structures, organizations can create a solid foundation for integrated care, enabling smoother implementation and more sustainable impact. These structures are not merely static elements but rather active tools that can be shaped and leveraged to drive organizational change towards integrated care.

People and Values: Driving Change from Within

The “People and Values” domain of the CCIC Framework highlights the crucial role of human factors and organizational culture in driving successful organizational change for integrated care. These seven capabilities focus on leadership, engagement, values, and attitudes, recognizing that sustainable change ultimately depends on the people within the organization and the shared values that guide their actions. These elements are essential organizational change tools, shaping the internal environment and driving buy-in for integrated care.

-

Leadership Approach*: This capability refers to the methods and behaviors used by formal leaders within the organization or network. As a change tool, leadership approach is paramount. Leaders who champion a clear vision for integrated care, empower staff, foster collaboration, and actively manage change are crucial for driving successful implementation. Different leadership styles (e.g., transformational, servant leadership) can be employed to inspire and motivate teams towards integrated care goals. Examples include leaders’ personal vision, strategies for staff empowerment, and leadership styles and competencies.

-

Clinician Engagement & Leadership*: This focuses on the formal and informal roles of clinicians, particularly physicians, in driving and supporting change. As a change tool, engaging clinicians is essential for the clinical credibility and practical implementation of integrated care. Actively involving clinicians in planning, leading, and implementing integrated care initiatives, empowering clinical champions, and creating clinical leadership roles ensures that changes are clinically relevant and effectively adopted. Examples include clinician involvement in planning, clinical champions, and physician leadership roles.

-

Organizational/Network Culture*: This refers to the widely shared values and habits within the organization or network. As a change tool, cultivating a culture that values collaboration, patient-centeredness, continuous learning, and innovation is fundamental for long-term success in integrated care. Culture change initiatives can involve articulating shared values, promoting collaborative behaviors, and celebrating successes in integrated care. Examples include shared perceptions of what is important and appropriate behavior.

-

Focus on Patient-Centeredness & Engagement: This capability reflects the commitment to placing patients at the center of clinical, organizational, and network decision-making. As a change tool, a strong focus on patient-centeredness ensures that integrated care interventions are truly meeting the needs and preferences of the people they are designed to serve. This involves actively soliciting and using patient feedback, involving patients in service design, and promoting shared decision-making in care delivery. Examples include collection of patient feedback, consideration of patient needs, and patient involvement in service co-design.

-

Commitment to Learning: This capability describes the presence of values and practices that support continuous development of new knowledge and insights. As a change tool, fostering a commitment to learning and continuous improvement is vital in the complex and evolving field of integrated care. This involves encouraging experimentation, creating forums for knowledge sharing, providing time and resources for reflection, and actively learning from both successes and failures. Examples include encouragement of experimentation, forums for learning from others, and resources for reflection.

-

Work Environment: This capability refers to how employees perceive and experience their job and workplace. As a change tool, creating a positive and supportive work environment is crucial for staff well-being and engagement, which in turn impacts the success of integrated care. This involves ensuring opportunities for input, promoting job satisfaction, addressing burnout, and fostering a sense of teamwork and shared purpose. Examples include opportunity for input, job satisfaction, and burnout levels.

-

Readiness for Change*: This capability measures the extent to which organizations and individuals are willing and able to implement change. As a change tool, assessing and enhancing readiness for change is a critical first step in any integrated care initiative. Addressing resistance to change, building awareness of the need for change, and fostering a sense of collective efficacy are essential for creating a receptive environment for integrated care implementation. Examples include attitudes toward change, openness to innovation, and alignment of change with organizational vision.

By nurturing these “People and Values” capabilities, organizations can create a fertile ground for organizational change in integrated care. These are not just soft skills but rather powerful drivers of transformation that shape the culture, mindset, and behaviors necessary for successful and sustainable integration.

Key Processes: Implementing and Sustaining Change

The “Key Processes” domain of the CCIC Framework focuses on the operational mechanisms and activities that are essential for implementing, delivering, and continuously improving integrated care. These capabilities represent the core workflows and practices that translate the structural foundation and people-centered values into tangible integrated care services. When optimized, these key processes serve as effective organizational change tools, enabling the practical realization of integrated care goals.

-

Partnering*: This capability refers to the development and management of formal and informal connections between different organizations and practices. As a change tool, effective partnering is at the heart of integrated care, particularly when it involves crossing organizational boundaries. This includes establishing clear communication channels, developing shared protocols, building trust and mutual understanding, and creating mechanisms for collaborative problem-solving. Examples include information sharing, staff sharing, collaborative problem-solving, and referral agreements.

-

Delivering Care*: This capability encompasses the methods used by providers in caring for patients within the organization and across the network. As a change tool, redesigning care delivery processes is fundamental to achieving integrated care. This involves implementing inter-professional teamwork models, developing joint care plans, utilizing standardized decision support tools, and promoting shared patient-provider decision-making. Examples include inter-professional teamwork, standardized decision support tools, and shared decision-making.

-

Measuring Performance: This refers to the systematic collection of data about how well the organization and network are meeting their goals. As a change tool, performance measurement is crucial for tracking progress, identifying areas for improvement, and ensuring accountability in integrated care initiatives. This includes developing shared performance measurement frameworks, regularly collecting and reporting data, and using data to drive quality improvement efforts. Examples include shared performance measurement frameworks, regular reporting, and data utilization for improvement.

-

Improving Quality: This capability focuses on the use of practices and processes that continuously enhance patient care. As a change tool, a robust quality improvement (QI) approach is essential for sustaining and enhancing the benefits of integrated care over time. This involves providing QI training to staff, systematically using QI methodologies (e.g., process mapping, control charts), and actively applying best practices in integrated care delivery. Examples include QI training, systematic use of QI methods, and application of best practices.

By focusing on these “Key Processes” capabilities, organizations can translate the vision of integrated care into practical, day-to-day operations. These processes are not static routines but rather dynamic tools that can be continuously refined and improved to enhance the effectiveness, efficiency, and patient-centeredness of integrated care delivery. Mastering these processes is crucial for sustaining organizational change and realizing the long-term benefits of integrated care.

Prioritizing Organizational Change Tools: Insights from Research

To validate and prioritize the organizational capabilities outlined in the CCIC Framework, a study was conducted involving semi-structured interviews with key informants involved in integrated care initiatives. The findings from this research provide valuable insights into which organizational change tools are perceived as most critical in practice.

Key Findings from the Study

The study, which included interviews with 29 individuals representing 38 integrated care networks, revealed that all 17 organizational capabilities in the CCIC Framework were recognized as relevant by participants. However, some capabilities emerged as particularly salient and were prioritized as “most important” by the interviewees.

Table 1 summarizes the frequency with which each capability was mentioned in the semi-structured discussions and ranked as “most important” in a graphic elicitation exercise during the interviews. Nine capabilities consistently emerged as priorities, defined as being among the top six most frequently mentioned and/or ranked factors. These prioritized capabilities are marked with an asterisk (*) in Figure 1 and Table 2.

Table 1: Organizational Contextual Factors and Capabilities That Most Influence the Implementation and Delivery of Integrated Care: Results of Key Informant Interviews (n = 29).

| Semi-Structured Discussion (frequency) | Graphic Elicitation Ranking (frequency) |

|---|---|

| Partnering (116) | Clinician Engagement & Leadership (16) |

| Resources (103) | Patient-Centeredness & Engagement (12) |

| Readiness for Change (78) | Leadership Approach (11) |

| Clinician Engagement & Leadership (70) | Readiness for Change (9) |

| Delivering Care (56) | Information Technology (9) |

| Leadership Approach (51) | Organizational/Network Culture (9) |

| Patient-Centeredness & Engagement (31) | Resources (8) |

| Commitment to Learning (30) | Delivering Care (8) |

| Information Technology (29) | Governance (7) |

| Measuring Performance (27) | Partnering (4) |

| Governance (26) | Improving Quality (9) |

| Physical Features (19) | Measuring Performance (27) |

| Accountability (18) | Commitment to Learning (2) |

| Organizational/Network Design (16) | Accountability (2) |

| Organizational/Network Culture (15) | Physical Features (1) |

| Improving Quality (9) | Organizational/Network Design (0) |

| Work Environment (6) | Work Environment (0) |

The prioritized capabilities span across all three domains of the CCIC Framework:

- Basic Structures: Resources* and Information Technology*.

- People and Values: Leadership Approach*, Clinician Engagement and Leadership*, Organizational/Network Culture*, Readiness for Change*, and Focus on Patient-Centeredness & Engagement.

- Key Processes: Partnering* and Delivering Care*.

Notably, three capabilities – Leadership Approach*, Clinician Engagement and Leadership*, and Readiness for Change* – were ranked in the top six in both the frequency of mention and the graphic elicitation ranking. This suggests that these “People and Values” capabilities were perceived as particularly critical for successful integrated care implementation by the study participants.

The Importance of “People and Values” in Change Management

The prominence of “People and Values” capabilities in the study findings underscores the critical role of human and cultural factors in organizational change, especially in the context of integrated care. While basic structures and key processes provide the necessary framework and operational mechanisms, it is the “People and Values” that truly drive and sustain change.

- Leadership Approach and Clinician Engagement: Effective leadership sets the vision, direction, and tone for change. Engaged clinicians, who are often at the forefront of care delivery, bring essential clinical expertise and credibility to integrated care initiatives. Their buy-in and active participation are crucial for successful implementation and adoption of new models of care.

- Organizational Culture and Readiness for Change: A culture that embraces collaboration, innovation, and patient-centeredness creates a fertile ground for integrated care to flourish. Readiness for change reflects the collective willingness and ability of the organization to adapt and evolve. Addressing resistance to change and fostering a positive attitude towards new ways of working are essential for overcoming implementation hurdles.

- Patient-Centeredness & Engagement: Ultimately, integrated care is about improving care for patients. A genuine commitment to patient-centeredness ensures that change efforts are aligned with patient needs and preferences. Engaging patients in the design and delivery of integrated care further strengthens its relevance and impact.

These findings align with Resource-Based Theory, which emphasizes that sustainable competitive advantage and superior performance are often derived from resources and capabilities that are difficult to imitate or substitute [13]. Many of the prioritized capabilities, such as organizational culture, readiness for change, and partnering, are intangible and deeply embedded within organizations. They are developed over time and are not easily replicated, making them powerful drivers of organizational success in integrated care.

Relationships Between Organizational Change Tools

The study also explored the interrelationships between different organizational capabilities, revealing how they influence and reinforce each other. Participants described numerous relationships, highlighting the interconnectedness of the CCIC Framework elements. Figure 2 depicts the most prominent hypothesized relationships based on the interview data.

The most frequently mentioned relationships involved Readiness for Change and Partnering, underscoring their central role in integrated care efforts. Three capabilities – Resources, Leadership Approach, and Organizational Design – emerged as influential factors impacting both Readiness for Change and Partnering.

- Resources and Readiness for Change: While some participants noted that adequate resources enhance confidence and momentum for change, others suggested that resource scarcity can actually increase readiness by highlighting the need for innovative, collaborative solutions. This suggests a potentially complex, non-linear relationship where the perception and management of resources may be as important as the absolute level of resources.

- Leadership Approach and Readiness for Change: Strong leadership is crucial for fostering readiness for change. Leaders can influence staff perceptions of the need for change, build buy-in, and provide support and direction to overcome resistance. Effective communication and engagement by leaders are key to shaping a positive attitude towards change.

- Organizational Design and Readiness for Change: More hierarchical and bureaucratic organizations were perceived as less flexible and less ready for change compared to flatter, more decentralized organizations. Organizational design choices can either facilitate or hinder adaptability and responsiveness to new initiatives like integrated care.

- Resources and Partnering: Resource availability can influence trust and willingness to partner. Perceived competition for scarce resources can create barriers to collaboration, while resource synergy can foster stronger partnerships. Organizations with more resources may also have a broader network of existing relationships to leverage for integrated care partnerships.

- Leadership Approach and Partnering: Leaders play a critical role in shaping the nature and tone of partnerships. They can foster a collaborative spirit, ensure that the “right people” are involved, and build trust and mutual understanding between partner organizations. A facilitative and inclusive leadership approach is essential for successful inter-organizational partnerships.

- Organizational Design and Partnering: Organizations with similar structures and levels of formality may find it easier to partner. Differences in hierarchy, centralization, and formalization can create challenges in communication, decision-making, and information sharing between partners. Understanding and bridging these organizational design differences is important for effective collaboration.

These interrelationships highlight that organizational change for integrated care is not about addressing isolated capabilities but rather about fostering a holistic and interconnected set of organizational strengths. A systems-thinking approach is essential, recognizing that improvements in one area can positively impact others, creating a virtuous cycle of organizational development.

Applying the CCIC Framework: Practical Tools and Strategies for Organizational Change

The CCIC Framework, along with the research findings, provides a practical toolkit for healthcare leaders and organizations seeking to drive successful organizational change for integrated care. It offers a structured approach to assess, plan, implement, and evaluate change efforts, focusing on the key organizational capabilities that are most critical for success.

Using the CCIC Framework as a Diagnostic Tool

The framework can be used as a diagnostic tool to assess an organization’s current state of readiness and capability for integrated care. This involves systematically evaluating each of the 18 capabilities across the three domains: Basic Structures, People and Values, and Key Processes.

- Self-Assessment: Organizations can use the framework to conduct internal self-assessments, engaging leadership, clinicians, and staff in evaluating their current capabilities. This can be done through surveys, workshops, or facilitated discussions, using the capability definitions and examples in Table 2 as a guide.

- Benchmarking: The framework can also be used for benchmarking, comparing an organization’s capabilities against best practices or peer organizations. This can provide insights into areas where the organization is lagging behind and where there is potential for improvement.

- Gap Analysis: By assessing current capabilities and comparing them to the capabilities required for successful integrated care implementation, organizations can identify key gaps that need to be addressed. This gap analysis informs the development of targeted change management strategies.

The diagnostic process should not only identify weaknesses but also highlight existing strengths. Leveraging existing strengths and building upon them can be an effective strategy for accelerating change and building momentum for integrated care initiatives.

Developing Targeted Change Management Strategies

Based on the diagnostic assessment, organizations can develop targeted change management strategies to build and strengthen the organizational capabilities most critical for their integrated care goals. The CCIC Framework provides a roadmap for developing these strategies, focusing on specific capabilities within each domain.

- Basic Structures: Strategies may focus on securing additional resources, investing in IT infrastructure, redesigning organizational structures, or strengthening governance and accountability mechanisms. For example, to improve IT capability, a strategy might involve implementing a shared electronic health record system across partner organizations.

- People and Values: Strategies may target leadership development, clinician engagement, culture change, enhancing readiness for change, or strengthening patient-centeredness. For example, to enhance leadership approach, a strategy might involve leadership training programs focused on change management and collaborative leadership. To foster clinician engagement, strategies could include establishing clinical leadership roles and creating forums for clinician input and decision-making.

- Key Processes: Strategies may focus on improving partnering processes, redesigning care delivery workflows, implementing performance measurement systems, or enhancing quality improvement capabilities. For example, to improve partnering, strategies might involve developing formal partnership agreements, establishing joint communication protocols, and creating mechanisms for collaborative problem-solving. To enhance care delivery processes, strategies could focus on implementing inter-professional team-based care models and developing shared care plans.

Change management strategies should be tailored to the specific context of the organization, taking into account its unique strengths, weaknesses, and challenges. They should be iterative and adaptive, allowing for adjustments based on ongoing monitoring and evaluation.

Partner Selection and Alignment for Effective Change

For integrated care initiatives that involve partnerships across multiple organizations, the CCIC Framework can inform partner selection and alignment. When choosing partners, organizations should consider their complementary strengths and capabilities, as well as potential areas of misalignment.

- Capability Complementarity: Seek partners who bring complementary capabilities. For example, an organization strong in community-based services might partner with a hospital system with strong acute care capabilities.

- Value Alignment: Prioritize partners with aligned values, particularly in areas like patient-centeredness, collaboration, and quality improvement. Shared values facilitate trust and collaboration, making partnerships more effective.

- Readiness for Change Compatibility: Consider partners’ readiness for change. Partners with similar levels of readiness may be more easily aligned and able to move forward together.

The CCIC Framework can also guide efforts to align capabilities across partner organizations. This may involve joint capacity building initiatives, shared training programs, or collaborative projects to strengthen specific capabilities across the network. Building shared capabilities fosters a more cohesive and effective integrated care network.

Monitoring and Evaluating Change Progress with the CCIC Framework

The CCIC Framework provides a structure for monitoring and evaluating the progress of organizational change efforts in integrated care. It can be used to track changes in organizational capabilities over time and assess the impact of change management strategies.

- 定期评估: 定期使用框架进行复评,以跟踪组织能力随时间的变化。这可以帮助评估变革管理策略的有效性,并识别需要进一步关注的领域。

- Performance Indicators: Develop performance indicators aligned with each of the 18 capabilities. Track these indicators over time to measure progress in capability development and identify areas where improvement is needed.

- Outcome Evaluation: Evaluate the impact of capability development on integrated care processes and outcomes. Assess whether improvements in organizational capabilities are leading to better care coordination, enhanced patient experiences, and improved health outcomes.

The framework can also be used for retrospective analysis, examining the organizational capabilities that contributed to the success or failure of past integrated care initiatives. Learning from past experiences is crucial for refining change management strategies and improving the likelihood of success in future efforts.

Conclusion: Embracing Organizational Change for Successful Integrated Care

The Context and Capabilities for Integrated Care (CCIC) Framework offers a valuable and comprehensive toolkit for navigating the complexities of organizational change in integrated care. By providing a structured understanding of key organizational capabilities across basic structures, people and values, and key processes, the framework empowers healthcare leaders and researchers to move beyond generic approaches and adopt targeted, context-sensitive strategies for driving successful integration.

The research findings underscore the paramount importance of “People and Values” capabilities, particularly leadership approach, clinician engagement, and readiness for change. These human and cultural factors are not merely supporting elements but rather the core drivers of sustainable transformation. Investing in leadership development, fostering a culture of collaboration and patient-centeredness, and actively engaging clinicians are essential for creating a receptive and enabling environment for integrated care.

The CCIC Framework is not a static blueprint but rather a dynamic tool that can be adapted and refined based on ongoing experience and research. It encourages a systems-thinking approach, recognizing the interconnectedness of organizational capabilities and the need for holistic change strategies. By embracing organizational change as a continuous journey of learning and adaptation, and by leveraging the CCIC Framework as a guiding tool, healthcare organizations can pave the way for more effective, patient-centered, and sustainable integrated care systems. Future research should continue to test and refine the framework, explore the interrelationships between capabilities in greater depth, and develop practical tools and resources to support its widespread adoption and application in diverse healthcare settings.

References

[1] World Health Organization. Integrated health services – what and why? World Health Organization. 2018. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/385154/Policy-Brief-Integrated-health-services-Eng.pdf. Accessed 28 Feb 2024.

[2] Leutz WN. Five laws of integrated care. Milbank Q. 1999;77(1):7–11.

[3] Kodner DL, Spreeuwenberg C. Integrated care: meaning, logic, implications, and pathways. Healthc Pap. 2002;3(2):1–47 discussion 48-52.

[4] Armitage GD, Suter E, O’Sullivan D, et al. Integrated care: what can we learn from the grey literature? Healthc Policy. 2009;4(3):97–116.

[5] Goodwin N, Smith J, Davies A, et al. Integrated care for older people with complex needs: building blocks for effective services. London: King’s Fund; 2012.

[6] Shaw J,ాయెం,械, Rosen R. Integrated care: experiences and opportunities in developed countries. World Health Organization. 2011.

[7] Axelsson R, Axelsson SB. Integration and collaboration in public health—a conceptual framework. Health Policy. 2006;79(1):75–87.

[8] Øvretveit J. Understanding the conditions for improvement – research to discover which context suits which improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(Suppl 1):i18–23.

[9] Shortell SM, Rundall TG. Physician involvement in hospital quality improvement: what difference does it make? Milbank Q. 2007;85(Suppl 2):499–527.

[10] Gillies RR, Shortell SM, Casalino LP, et al.remic organizations in California: development and validation of a measurement instrument. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(5):1619–43.

[11] Suter E,пова, Oelke ND, et al. Integrating primary health care and public health: key functions and organizational arrangements across different models. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:281.

[12] Harrison MI. Models of organizational culture and quality of care: a synthesis. Qual Health Care. 1993;2(3):181–90.

[13] Barney JB. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manage. 1991;17(1):99–120.

[14] Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Promoting implementation of health services research findings in practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

[15] Meyers DC, Durlak JA, Wandersman A. Implementation science in community psychology: the state of the science. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50(3–4):329–50.

[16] Winter SG. Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strateg Manage J. 2003;24(10):991–5.

[17] Valentine DP,ень, Clark J, et al. Interprofessional teamwork for integrated care: a systematic review. Int J Integr Care. 2011;11:e127.

[18] Singer SJ, Vogus TJ, Shields HM. Patient safety climate in intensive care units. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(5):385–92.

[19] Alexander JA, Weiner BJ, Metzger J, et al. The diffusion of interorganizational service coordination in hospital-based systems of care. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(4):1175–200.

[20] Kreindler SA, Gray J, Wright S, et al. Evaluation of a Canadian interdisciplinary primary care diabetes model: a mixed-method study. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:188.

[21] Hogg WE, Rowan MS, Russell G, et al. Effect of systematic use of the patient enablement instrument (PEI) on health related quality of life in primary care patients: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2007;335(7628):949.

[22] Toth M, Solberg LI, Margolis KL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of outreach facilitation of guideline-based care for older adults with diabetes and hypertension: REACH-OUT. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(13):1423–30.

[23] Conrad DA, Mick SS, Madden CW, et al. Vertical integration: impact on hospital diversification and efficiency. Health Serv Res. 1988;23(2):233–50.

[24] Dranove D, Shanley M. Value of hospitals is related to their size. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(6):1644–53.

[25] Clement JP, McCue MJ, Wheeler JR, et al. Cost and charge effects of hospital system affiliation: investor-owned vs not-for-profit systems. Health Serv Res. 1995;30(1 Pt 1):27–47.

[26] McDonald R, Harrison R, Checkland K, et al. ধাক্কা, and context in quality improvement collaboratives: a qualitative study in primary care. BMJ. 2007;334(7589):399.

[27] Lemieux M, Bird M,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,ử,

[28] Pa