Background

Injuries represent a significant global public health challenge, leading to substantial premature mortality and long-term disabilities with far-reaching socioeconomic consequences [1, 2]. In 2019, injuries, encompassing road traffic accidents, unintentional injuries, self-harm, and interpersonal violence, accounted for 4.3 million deaths worldwide, constituting 10% of all deaths and over 40 million years lived with disability (YLDs) [1, 3, 4]. While injuries affect individuals of all ages, young people are particularly vulnerable [1–3, 5, 6]. Furthermore, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) bear a disproportionately high burden of injuries [3, 4]. The 2019 Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors (GBD) study highlights significant regional disparities in injury incidence globally [6], with over 90% of global injuries occurring in LMICs, where safety measures and access to medical services are often inadequate [3, 5].

Ethiopia, a resource-constrained nation, faces an unknown burden of injury due to limited injury surveillance systems [7–10]. Existing studies often focus on specific injury types within healthcare facilities or are small-scale surveys, failing to provide comprehensive data for evidence-based interventions [11–13]. The country has also experienced frequent intergroup conflicts stemming from political disputes [14–16]. Unintentional injuries, such as drowning, falls, poisoning, and animal encounters, are growing public health concerns [8, 17–20]. Notably, road traffic injuries are a leading cause of premature deaths and long-term disabilities in Ethiopia [7, 8]. Studies in Addis Ababa healthcare facilities indicate a high burden of road traffic injuries, contributing significantly to injury-related admissions and fatalities [11, 20]. A systematic review further confirms a high prevalence (32%) of road traffic injuries among trauma patients in Ethiopia, with regional variations from 14% to 60% [21].

The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) emphasize the detrimental impact of injuries on development and health [22]. The SDGs include targets for violence and injury prevention, establishing a framework for cross-sectoral preventative action [23]. Monitoring progress towards these goals requires high-quality data analysis. However, systematic investigations of injuries at national and sub-national levels in Ethiopia remain limited. This lack of evidence hinders the development of effective prevention strategies and support systems for survivors needing medical and psychosocial care. Therefore, this study aims to estimate the incidence, prevalence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost, years of life lost (YLLs), and YLDs due to injuries, and their associated causes across all regions and chartered cities in Ethiopia from 1990 to 2019, using data from the 2019 GBD study. The study’s findings are intended to inform policies and programs focused on enhancing injury prevention strategies and improving societal well-being in Ethiopia.

Methods

Setting

Ethiopia, the second most populous country in Africa, had an estimated population of 112 million in 2019 [24]. Administratively, it is divided into 10 regional states and two chartered cities. The median age is 20 years, with an annual population growth rate of 2.5% in 2020 [24]. Over 80% of the population resides in rural areas with limited healthcare access [25].

Data Sources, Processing, and Analyses

This study utilized data from the 2019 GBD study, accessed via GBD Compare [6, 26]. The 2019 GBD study adheres to reporting guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates [27]. It employs a hierarchical classification system based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) to categorize causes of premature death and disability, ensuring mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive results [6]. Injury incidence and death in the 2019 GBD are classified using ICD-9 codes E000-E999 and ICD-10 chapters V to Y, excluding alcohol poisoning and drug overdoses, which are categorized under substance use disorders. Cause-specific mortality was estimated using a cause of death ensemble model incorporating covariate selection algorithms [6]. The GBD study quantifies health loss due to diseases, injuries, and risk factors by age, sex, and geography over time, providing regular estimates of mortality, cause-specific deaths, DALYs, YLLs, and YLDs for a comprehensive list of causes from 1990 to 2019 [6]. These estimates cover 204 countries and territories, grouped into 21 regions and seven super-regions.

Input data for injuries are sourced from international databases capturing cause-specific fatal events and supplemented with data addressing quality, representativeness, or reporting delays [6]. GBD estimates are updated for the entire time series with new data and methodological refinements, ensuring results supersede previous rounds. Spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression is used to enhance data across locations and time. GBD injury estimates for Ethiopia were derived from police reports, the Addis Ababa mortality surveillance program, the Ethiopian Health and Demographic Surveillance System, and surveys such as Demographic and Health Surveys. The complete list of data sources is available at: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019/data-input-sources.

This analysis extracted injury estimates for incidence, prevalence, mortality, DALYs, YLLs, YLDs, and associated causes across Ethiopian regions and chartered cities from 1990 to 2019. All rates were age-standardized and aggregated by socio-demographic categories, regions, and cities. Trends were analyzed over the study period. 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs) were presented for summary statistics, generated using the 25th and 97.5th ordered values from 1,000 posterior distribution draws. Detailed estimation techniques are published elsewhere [6, 28].

Results

Incidence and Prevalence

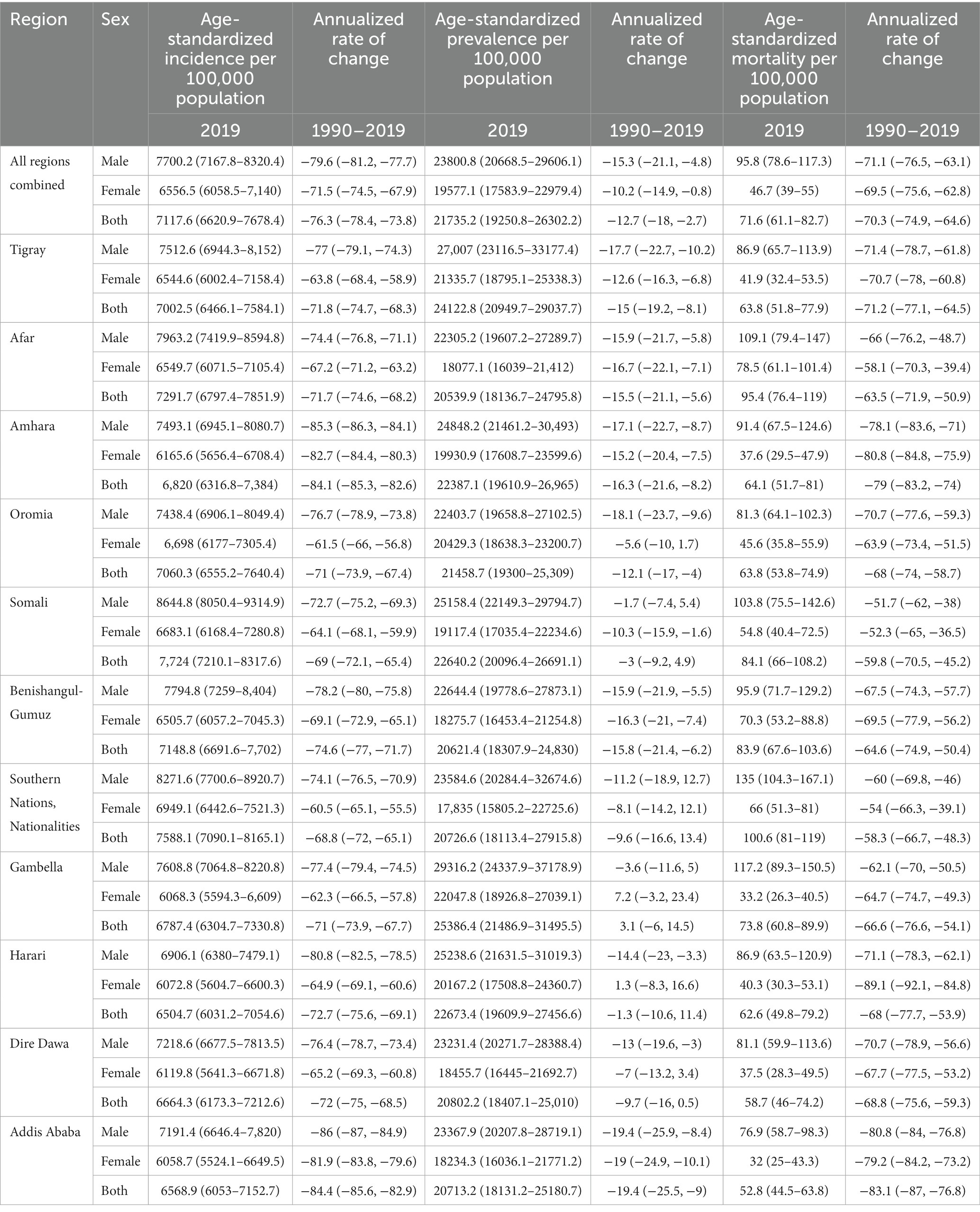

In 2019, there were an estimated 8.1 million (95% UI: 7.4–8.9) new injury cases in Ethiopia, with 4.3 million in males and 3.8 million in females. Prevalent cases were estimated at 16.6 million (95% UI: 14.7–20.0), with 8.7 million in males and 7.8 million in females. The age-standardized incidence rate was 7,118 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 6,621–7,678), and the prevalence rate was 21,735 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 19,251-26,302). The Somali region had a higher incidence rate [7,724 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 7,210–8,318)], followed by the Southern Nations and Nationalities and Peoples’ region [7,588 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 7,090–8,165)]. Gambella region had a higher prevalence rate [25,386 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 21,487–31,496)], followed by Tigray region [24,123 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 20,950–29,038)]. Between 1990 and 2019, the age-standardized incidence rate decreased by 76% (95% UI: 74–78), and the prevalence rate by 13% (95% UI: 3–18). The most significant reductions were observed in Addis Ababa, Amhara, and Benishangul-Gumuz regions (Table 1).

Mortality

In 2019, an estimated 43,658 (95% UI: 37,027-51,499) injury-related deaths occurred, with 30,430 in males and 13,228 in females, accounting for 7.8% of all deaths in Ethiopia (9.5% for males vs. 5.4% for females). The age-standardized death rate was 72 deaths per 100,000 population (95% UI: 61–83), with 96 per 100,000 males and 47 per 100,000 females. Higher death rates were observed in the Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ region [101 deaths per 100,000 population (95% UI: 81–119)], Afar region [95 deaths per 100,000 population (95% UI: 76–119)], Somali region [84 deaths per 100,000 population (95% UI: 66–108)], Benishangul-Gumuz region [84 deaths per 100,000 population (95% UI: 68–104)], and Gambella region [74 deaths per 100,000 population (95% UI: 61–90)]. A 70% (95% UI: 65–75) reduction in injury-related death rate occurred between 1990 and 2019, with inter-regional variations (Table 1; Figure 1).

Disability-Adjusted Life Years Lost

Injuries resulted in an estimated 2.8 million (95% UI: 2.4–3.0) DALYs lost in 2019, representing 7.4% of total DALYs lost in Ethiopia (9.0% for males vs. 6.4% for females). The age-standardized DALY rate was 3,265 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 2,826–3,783), over three times lower than the 1990 estimate of 11,386 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 10,561–12,165). Higher DALY rates were observed in the Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ region [4,227 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 3,482–5,083)], Afar region [4,041 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 3,307-4,975)], Benishangul-Gumuz region [3,950 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 3,299–4,716)], Somali region [3,884 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 3,174–4,797)], and Gambella region [3,362 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 2,751–4,070); Table 2]. DALY burden peaked at age 24 and decreased thereafter (Figure 2).

Years of Life Lost

In 2019, an estimated 2.2 million (95% UI: 1.8–2.6) YLLs occurred, nearly three times lower than the 1990 estimate of 6.1 million (95% UI: 6.1–6.5) YLLs. The age-standardized YLL rate was 2,417 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 2,043–2,860). Higher YLL rates were observed in the Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ region [3,392 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 2,705–4,101)], Afar region [3,234 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 2,489–4,129)], Benishangul-Gumuz region [3,132 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 2,507–3,896)], and Somali region [2,970 per 100,000 population (95% UI: 2,329–3,768)]. Males experienced higher YLL rates across all regions (Table 2). YLL burden peaked at age 24 and declined with age (Figure 2).

Years Lived with Disability

Injuries contributed to 630,454 (95% UI: 460,443–865,634) YLDs in Ethiopia in 2019, with an age-standardized rate of 848 years per 100,000 population [95% UI: (620–1,153)]. Higher YLD rates were found in Gambella region [1,023 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 741–1,391)], Harari region [986 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 715–1,325)], Tigray region [956 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 703–1,282)], Somali region [914 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 669–1,213)], Amhara region [873 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 642–1,171)], and Dire Dawa city administration [850 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 629–1,134)]. YLD rates were higher among males in every region (Table 2). YLD burden increased until age 34 and then decreased (Figure 2).

The Leading Causes of Injuries

The top five causes of incident injuries in 2019 were exposure to mechanical forces [1,381 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 1,098–1,674)], animal contacts [1,209 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 1,000–1,486)], falls [1,162 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 958–1,400)], foreign bodies [1,158 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 939–1,434)], and transport injuries [1,089 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 927–1,277)]. The most common causes of prevalent injuries were conflict and terrorism [4,889 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 2,608–9,342)], interpersonal violence [3,640 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 3,208–4,175)], transport injuries [3,183 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 2,962–3,451)], exposure to mechanical forces [2,688 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 2,327–3,060)], and falls [2,440 cases per 100,000 population (95% UI: 2,116–2,823)]. Since 1990, prevalence of transport injuries decreased by 32% (95% UI: 31–33), motorcycle injuries by 29% (95% UI: 27–31), motor vehicle injuries by 28% (95% UI: 26–30), exposure to mechanical forces by 12% (95% UI: 10–14), and interpersonal violence by 7.4% (95% UI: 5–10). However, falls increased by 8.4% (95% UI: 7–11) and conflict and terrorism by 1.5% (95% UI: 38–27; Table 3).

The top five causes of injury-related deaths in 2019 were transport injuries [15 deaths per 100,000 population (95% UI: 13–18)], interpersonal violence [10 deaths per 100,000 population (95% UI: 8–12)], self-harm [10 deaths per 100,000 population (95% UI: 8–13)], falls [10 deaths per 100,000 population (95% UI: 8–11)], and poisoning [four deaths per 100,000 population (95% UI: 3–5)]. Since 1990, death rates decreased for poisoning by 61% (95% UI: 44–71), transport injuries by 55% (95% UI: 40–66), self-harm by 53% (95% UI: 33–65), interpersonal violence by 38% (95% UI: 13–57), and falls by 21% (95% UI: 13–41; Table 3).

The top five causes of DALYs lost in 2019 were transport injuries [760 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 647–891)], interpersonal violence [457 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 381–557)], self-harm [333 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 268–419)], falls [300 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 252–354)], and exposure to mechanical forces [221 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 166–285)]. Since 1990, DALYs lost decreased for self-harm by 57% (95% UI: 39–69), transport injuries by 56% (95% UI: 44–66), interpersonal violence by 39% (95% UI: 16–56), exposure to mechanical forces by 38% (95% UI: 16–57), and falls by 23% (95% UI: 2–39). Major causes of YLDs were transport injuries [216 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 159–283)], conflict and terrorism [212 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 116–431)], and falls [123 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 89–166)]. Leading causes of YLLs were transport injuries [545 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 452–661)], interpersonal violence [408 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 333–505)], and self-harm [325 years per 100,000 population (95% UI: 259–411); Table 4].

Discussion

This analysis, utilizing GBD study data, assessed the burden and trends of injury-related morbidity and mortality at national and sub-national levels in Ethiopia from 1990 to 2019. While injury-related deaths have significantly decreased over three decades, they still account for 7.8% of all-cause deaths. Notably, injury deaths exceed the combined deaths from malaria and tuberculosis, highlighting their public health significance. The 70% reduction in death rate between 1990 and 2019 may be linked to Ethiopia’s socioeconomic progress, including improved access to health, education, and social services [29]. Evidence suggests that better living conditions, poverty reduction, and improved service access are determinants of injury-related outcomes [30–33]. However, 2019 data are comparable to a 2017 study [8], indicating that injury reduction is not progressing rapidly enough to meet the 2030 SDG target.

Sub-nationally, the Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ region exhibits the highest injury-related deaths and DALYs, followed by the Afar region. Regional comparisons in Ethiopia are limited, but a review of road injuries indicated higher disability in the Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ region [21]. Factors such as population density, youth mobility, trafficking, and migration [34–36], along with ethnic diversity potentially linked to interpersonal violence, may contribute to this. Gambella and Tigray regions were disproportionately affected by YLDs and prevalence rates. Tigray’s history of conflict [14, 16], despite healthcare and infrastructure improvements [37], and Gambella’s history of intergroup conflicts [14] may contribute to these findings. The Ethio-Eritrean war likely contributed to peak injury death rates in 1999-2000 [14, 16]. Despite these regional variations, all regions have shown reductions in injury-related death and disability over the past 30 years. However, the absolute number of injuries has not significantly decreased, even increasing from 2010-2019, possibly due to increased development activities and population growth [38], while improved healthcare may have increased survival from severe injuries.

Throughout the study period, males were disproportionately affected by injuries, consistent with global trends [5, 39, 40]. Patriarchal societal norms in Ethiopia may contribute to men’s higher risk-taking behaviors, such as unsafe driving, workplace practices [7, 41, 42], and involvement in armed conflicts [42, 43]. Higher substance use among males may also increase aggression and injury risk [41, 42]. Age distribution analysis reveals higher injury death and disability risk among younger age groups, potentially due to less adherence to safety precautions, risk-taking, and injury-prone activities [41, 44, 45].

Approximately 79% of injury-related deaths were caused by road traffic injuries, interpersonal violence, self-harm, falls, and poisoning. Road traffic injuries as the leading cause aligns with global injury rankings [6] and account for a significant proportion of injury-related hospitalizations and fatalities in Ethiopia [7, 10, 11, 20]. The Ethiopian health sector recognizes road traffic injuries as a major public health issue [37].

Interpersonal violence and self-harm are also leading causes of premature death in Ethiopia, consistent with surveillance data [12]. Falls are emerging as a significant cause of injury-related death and disability [12, 13], ranking as the fourth leading cause of death nationally, with deaths and DALYs increasing by 55% and 46% respectively between 1990 and 2019. This may be linked to an aging population and increased life expectancy [38], as older adults are more prone to falls and related health consequences [13].

GBD methodology strengths and limitations are detailed elsewhere [5, 6]. This study’s strengths include comprehensive sub-national representation using available Ethiopian data sources, enhancing estimate validity beyond individual surveys. However, the absence of a robust injury surveillance and vital registration system may introduce uncertainty in determining injury mortality causes.

Injury Prevention Initiatives in Ethiopia

Historically, injury prevention has been overlooked in Ethiopia, overshadowed by communicable disease control, despite its substantial burden. However, recent years have seen increased attention to injury prevention [37, 46]. Various government bodies, including the Ministries of Health, Transport, and Women and Child Affairs, are engaged in injury prevention efforts, which can be further strengthened by this study’s findings. For example, emergency surgeries are included in the Ethiopian essential health services package [46], and the Ministry of Women and Children Affairs addresses gender-based violence. Individual activists, leaders, and artists advocate for safety and injury prevention, challenging misconceptions about preventability. Local NGOs like Save The Nation focus on capacity building and road safety awareness. Insurance agencies are covering emergency healthcare costs for injury victims. This study provides evidence to inform stakeholders’ priority setting, resource mobilization, and advocacy in injury prevention.

Conclusion

In Ethiopia, injury-related deaths, incidence, prevalence, DALYs, YLLs, and YLDs have steadily decreased over the past 30 years, but the burden remains high with regional disparities. Traffic injuries, falls, self-harm, and interpersonal violence are major contributors to deaths and disabilities. Children under 5, adolescents, and young adults are disproportionately affected. Most injuries are preventable through public health measures, road safety, and security interventions. Coordinated efforts by researchers, public health authorities, and policymakers are crucial to further reduce the burden of injury in Ethiopia.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because one can access them from the IHME repository directly. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to http://ghdx.647healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

TB conceived, designed, and conducted the study. ST, AM, and MS consulted the overall process of the study. ST, TB, AM, MS, FG, GT, SW, SMe, SMo, AW, and MN involved in the analysis and interpretation of the findings. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The GBD study is a systematic, scientific, and global effort to quantify and compare the magnitude of health loss from disease, injury, and risk factors by age, sex, and population over time. We are grateful for this global initiative.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- World Health Organization Injuries and violence: The facts. (2014). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization . Injuries and violence. (2021) Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/injuries-and-violence (Accessed December 12, 2021).

- Laytin, AD , and Debebe, F . The Burden of Injury in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: Knowing What We Know, Recognising What We Don’t Know. London, UK: BMJ Publishing Group and the British Association for Accident. (2019).

- Haagsma, JA , Graetz, N , Bolliger, I , Naghavi, M , Higashi, H , Mullany, EC, et al. The global burden of injury: incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the global burden of disease study 2013. Inj Prev. (2016) 22:3–18. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041616

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- James, SL , Castle, CD , Dingels, ZV , Fox, JT , Hamilton, EB , Liu, Z, et al. Global injury morbidity and mortality from 1990 to 2017: results from the global burden of disease study 2017. Inj Prev. (2020) 26:i96–i114. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043494

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Vos, T , Lim, SS , Abbafati, C , Abbas, KM , Abbasi, M , Abbasifard, M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. (2020) 396:1204–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Abegaz, T , and Gebremedhin, S . Magnitude of road traffic accident related injuries and fatalities in Ethiopia. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0202240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202240

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Ali, S , Destaw, Z , Misganaw, A , Worku, A , Negash, L , Bekele, A, et al. The burden of injuries in Ethiopia from 1990-2017: evidence from the global burden of disease study. Inj Epidemiol. (2020) 7:67. doi: 10.1186/s40621-020-00292-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Anteneh, A , and Endris, BS . Injury related adult deaths in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: analysis of data from verbal autopsy. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:926. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08944-7

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Abegaz, T , Berhane, Y , Worku, A , Assrat, A , and Assefa, A . Road traffic deaths and injuries are under-reported in Ethiopia: a capture-recapture method. PLoS One. (2014) 9:e103001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Getachew, S , Ali, E , Tayler-Smith, K , Hedt-Gauthier, B , Silkondez, W , Abebe, D, et al. The burden of road traffic injuries in an emergency department in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Public Health Act. (2016) 6:66–71. doi: 10.5588/pha.15.0082

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Gelaye, KA , Tessema, F , Tariku, B , Abera, SF , Gebru, AA , Assefa, N, et al. Injury-related gaining momentum as external causes of deaths in Ethiopian health and demographic surveillance sites: evidence from verbal autopsy study. Glob Health Action. (2018) 11:1430669. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2018.1430669

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Janakiraman, B , Temesgen, MH , Jember, G , Gelaw, AY , Gebremeskel, BF , Ravichandran, H, et al. Falls among community-dwelling older adults in Ethiopia; A preliminary cross-sectional study. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0221875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221875

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Fritzen, A , Byon, H , Nowakovski, A , and Pallock, A. Ethiopia: a risk assessment brief. Based on CIFP risk assessment methodology. (2006).

- Pausewang, S , Tronvoll, K , and Aalen, L . Conclusion: Democracy Unfulfilled? Ethiopia Since the Derg: A Decade of Democratic Pretension and Performance. (2002) London: Zed Books, 230–244

- Bezabih, WF . Fundamental consequences of the Ethio-Eritrean war [1998-2000]. J Conflictol. (2014) 5:39–47. doi: 10.7238/joc.v5i2.1919

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Guracho, YD , and Bifftu, BB . Women’s attitude and reasons toward justifying domestic violence in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Afr Health Sci. (2018) 18:1255–66. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v18i4.47

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Yitbarek, K , Woldie, M , and Abraham, G . Time for action: intimate partner violence troubles one third of Ethiopian women. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0216962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216962

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Amare, T , Meseret Woldeyhannes, S , Haile, K , and Yeneabat, T . Prevalence and associated factors of suicide ideation and attempt among adolescent high school students in Dangila town, Northwest Ethiopia. Psychiatry J. (2018) 2018:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2018/7631453

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Wolde, A , Abdella, K , Ahmed, E , Tsegaye, F , Babaniyi, OA , Kobusingye, O, et al. Pattern of injuries in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a one-year descriptive study. East Centr African J Surg. (2008) 13:14–22.

- Endalamaw, A , Birhanu, Y , Alebel, A , Demsie, A , and Habtewold, TD . The burden of road traffic injury among trauma patients in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Afric J Emerg Med. (2019) 9:S3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2019.01.013

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Lee, BX , Kjaerulf, F , Turner, S , Cohen, L , Donnelly, PD , Muggah, R, et al. Transforming our world: implementing the 2030 agenda through sustainable development goal indicators. J Public Health Policy. (2016) 37:13–31. doi: 10.1057/s41271-016-0002-7

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Manandhar, M , Hawkes, S , Buse, K , Nosrati, E , and Magar, V . Gender, health and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Bull World Health Organ. (2018) 96:644–53. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.211607

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- United Nation’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division World population prospects: The 2019 revision Ethiopia population. (2021). Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/ethiopia-population/ (Accessed December 11, 2021).

- Central Statistical Agency Population projections for Ethiopia 2007–2037. (2012)

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . Protocol for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors study (GBD). (2019). Available at: https://www.healthdata.org/gbd/about/protocol (Accessed December 11, 2021).

- Stevens, GA , Alkema, L , Black, RE , Boerma, JT , Collins, GS , Ezzati, M, et al. Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: the GATHER statement. Lancet. (2016) 388:e19–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30388-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Kyu, HH , Abate, D , Abate, KH , Abay, SM , Abbafati, C , Abbasi, N, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. (2018) 392:1859–922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32335-3

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Rekiso, ZS . Education and economic development in Ethiopia, 1991–2017 In: F Cheru, C Cramer, and A Oqubay, editors. The Oxford Handbook of the Ethiopian Economy. Oxford Handbooks: Oxford Academic Press (2019)

- Fleischmann, A . Suicide in the world In: D Wasserman , editor. Suicide: An Unnecessary Death. 2nd edn. London: Oxford University Press (2016)

- Tsai, AC . Intimate partner violence and population mental health: why poverty and gender inequities matter. PLoS Med. (2013) 10:e1001440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001440

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Damtie, D , and Siraj, A . The prevalence of occupational injuries and associated risk factors among workers in Bahir Dar textile share company, Amhara region, Northwest Ethiopia. J Environ Public Health. (2020) 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2020/2875297

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- McClure, R , Kegler, S , Davey, T , and Clay, F . Contextual determinants of childhood injury: a systematic review of studies with multilevel analytic methods. Am J Public Health. (2015) 105:e37–43. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302883

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Messner, JJ , Haken, N , Maglo, M , Natalie, F , Wendy, W , Sarah, C, et al. Fragile states index-annual report 2020. (2020) Washington, DC: Fund for Peace.

- Humanitarian and Development Program . East Africa and the horn in 2022: An outlook for strategic positioning in the region. (2017) Institut De Relations Internationales Et Stratégiques, Paris, France.

- Bundervoet, T. Internal Migration in Ethiopia. (2018) World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group.

- Federal Ministry of Health Health sector transformation plan (II). (2021) Addis Ababa: Ethiopia. Federal Ministry of Health.

- Vollset, SE , Goren, E , Yuan, CW , Cao, J , Smith, AE , Hsiao, T, et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet. (2020) 396:1285–306. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30677-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Sorenson, SB . Gender disparities in injury mortality: consistent, persistent, and larger than you’d think. Am J Public Health. (2011) 101:S353–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300029

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Borse, N , and Sleet, DA . CDC childhood injury report: patterns of unintentional injuries among 0 to 19 year olds in the United States, 2000-2006. Fam Commun Health. (2009) 32:189. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000347986.44810.59

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization (2019). Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Byhoff, E , Tripodis, Y , Freund, KM , and Garg, A . Gender differences in social and behavioral determinants of health in aging adults. J Gen Intern Med. (2019) 34:2310–2. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05225-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Moser, C , Moser, CO , and Clark, DF . Victims, Perpetrators or Actors? Gender, Armed Conflict and Political Violence Palgrave Macmillan (2001).

- Naghavi, M , Pourmalek, F , Shahraz, S , Jafari, N , Delavar, B , and Motlagh, ME . The burden of injuries in Iranian children in 2005. Popul Health Metrics. (2010) 8:5. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-8-5

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Mulugeta, H , Tefera, Y , Abegaz, T , and Thygerson, SM . Unintentional injuries and sociodemographic factors among households in Ethiopia. J Environ Public Health. (2020) 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2020/1587654

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

- Federal Ministry of Health Essential health services package of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Ministry of Health (2019).