Family-based intervention programs have long been a cornerstone of psychology, utilizing theory-driven models to foster child development. Early evidence-based parenting programs in the 1970s, aimed at addressing child problem behavior, were built upon causal models derived from longitudinal developmental research. Today, these translational strategies are vital in designing programs that incorporate the burgeoning scientific understanding of how early adverse experiences impact neurobiological systems. By targeting not only behavioral outcomes but also the underlying neural systems, interventions can become more focused and effective, especially for vulnerable populations like children in foster care. This chapter delves into the development of a research program centered on an intervention tool for young children in foster care. Rooted in social learning theory and employing a translational neuroscience framework, this intervention offers a promising avenue for enhancing well-being. We will explore the conceptual model guiding this research, which integrates behavioral domains with stress-regulatory neural systems, and discuss future directions for translational neuroscience in family-based intervention research.

Decades of dedicated research have focused on creating and evaluating family-centered interventions designed to lessen the impact of environmental adversity, such as poverty, maltreatment, and community violence. While this body of work has convincingly demonstrated that the negative effects of adversity can be reversed, its overall impact on population health remains limited (Shonkoff & Fisher, 2013). This restricted progress might be partly due to the slow adoption of evidence-based interventions within community settings. However, even with increased adoption rates, the overall impact is uncertain, as intervention trials often report only modest effect sizes. Furthermore, scaling interventions often faces hurdles such as low participation rates, challenges in maintaining program fidelity and sustainability, and high implementation costs. Simply put, there is a pressing need for more impactful interventions and scalable strategies that lead to noticeable improvements in well-being for individuals exposed to adversity at a population level.

This chapter argues that adopting “experimental medicine” approaches to intervention development and evaluation (Pine & Leibenluft, 2015) is crucial for making progress in this field. Experimental medicine, by definition, focuses on identifying specific targets for interventions. It uses intervention trials as experimental tests of theory, where comparing intervention and control groups in terms of changes in targets and outcomes – and the relationships between these changes – provides empirical evidence for the validity of a proposed conceptual model (Insel et al., 2013). Advances in developmental neuroscience now enable non-invasive measurement of numerous brain and biological systems known to be affected by early adversity. These include stress hormone systems, brain systems involved in attention, threat detection, motivation, and reward, as well as immune and inflammatory systems (Chiang, Taylor, & Bower, 2015; Shonkoff et al., 2012; Tyrka, Burgers, Philip, Price, & Carpenter, 2013). This progress has fueled interest in applying experimental medicine approaches to develop and evaluate translational neuroscience interventions. These interventions can help clarify the neural mechanisms underlying developmental psychopathology and determine whether targeting these mechanisms through family-based interventions can reduce childhood symptoms and psychopathology (Fisher & Berkman, 2015).

In the following sections, we will explore the opportunities and challenges in using translational neuroscience to address the effects of adversity within the family intervention field. We will begin by describing how experimental methods were initially applied to family intervention by Gerald Patterson and his colleagues during the development of coercion theory (Patterson, 1982). We will examine how Patterson et al.’s work, including causal modeling of longitudinal data, led to a conceptual model that, in turn, generated evidence-based intervention strategies for treating disruptive behavior in children. We will present a description of the early randomized clinical trials used to evaluate these intervention strategies and experimentally test coercion theory. A brief overview will be given of how this progressed to subsequent iterations of theory and practice, including the developmentally downward extension of a coercion theory-based treatment from delinquent adolescents to preschool-aged foster children. This intervention for foster preschoolers provided a unique opportunity for one of the first “translational neuroscience” research programs, incorporating hypothesized neurobiological mechanisms alongside behavioral variables. We will present results from studies conducted within this research program. Finally, the chapter will conclude by considering future directions for research in this important area.

The Social Learning Model: An Experimental Approach to Family-Based Interventions

The idea of using experimental approaches in family-based interventions has been discussed for decades. In the 1960s, some researchers began to critique the prevalent correlational approaches in developmental psychology. Gerald Patterson, a pioneering researcher, moved beyond correlational research in family studies (Patterson, Reid, & Eddy, 2002). Starting in the late 1960s, Patterson and his team at the Oregon Social Learning Center began studying families in their natural environments. Instead of relying solely on questionnaires and interviews, they employed direct observation methods and microsocial coding to quantify parent-child interactions in naturalistic settings. Families were also studied longitudinally at frequent intervals to understand how processes observed at one point in time related to later outcomes, both positive and negative, throughout childhood and adolescence.

Patterson’s work largely focused on the development and maintenance of antisocial and disruptive behavior in children. It was already understood that intra-individual factors like difficult child temperament, family factors such as parental substance use and maternal depression, and sociocultural factors like poverty, discrimination, and community violence contributed to child problems. However, a key finding from Patterson’s research was that these variables are best understood as distal, or indirect, influences on child outcomes (Capaldi, DeGarmo, Patterson, & Forgatch, 2002). In contrast, parenting processes consistently emerged as the most proximal predictors of child antisocial behavior. Specifically, families characterized by (a) harsh and inconsistent discipline strategies and (b) low levels of warmth and support were more likely to have children with disruptive behavior problems (Capaldi et al., 2002). While the distal variables were undoubtedly important, their influence was primarily through their disruption of effective parenting processes. Longitudinal observations of families with children exhibiting disruptive behavior revealed that negative interactions between parents and children escalated over time as both parties increasingly used coercive strategies to end hostile interactions (Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992). These escalating interactions appeared to reinforce negative behavior in children, leading to difficulties in adapting to the academic and social demands of school. Subsequently, these family interactions predicted a range of negative outcomes, including school failure, rejection by prosocial peers, substance abuse, and delinquent behavior (Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989). A crucial aspect of Patterson and colleagues’ early work on family coercion was the malleability of the core family processes identified as primary causes of disruptive behavior development. This suggested the potential to intervene and modify key predictors of child disruptive behavior: harsh and inconsistent parenting coupled with a lack of support for positive behavior.

To investigate whether changes in parenting could effectively alter the development of disruptive child behavior, Patterson and colleagues developed a set of intervention strategies known as Parent Management Training Oregon (PMTO; Patterson, Chamberlain, & Reid, 1982). Over the years, numerous independent randomized clinical trials have confirmed the effectiveness of PMTO strategies in improving relevant parenting domains (Kazdin, 1997). Moreover, improvements in parenting were linked to reductions in problem behavior and increases in prosocial behavior (Kazdin, 1997. These trials not only demonstrated the efficacy of PMTO as an intervention tool to promote child well-being but also strengthened the evidence supporting the coercion model.

Expanding the Coercion Model: Integrating Neurobiological Domains

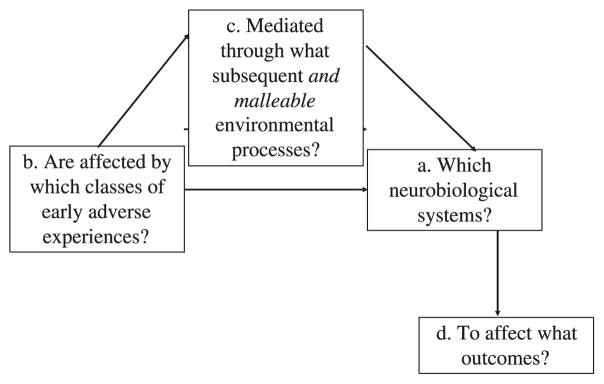

The iterative process that led to PMTO exemplifies how an experimental approach can be applied to family intervention research. While incorporating a translational neuroscience focus might not seem immediately obvious, it is a logical extension. However, this requires broadening the focus from solely behavioral targets and outcomes to include the underlying neural processes mediating the relationship between targets and outcomes. As illustrated in Figure 7.1, this approach leads to considering: (a) specific neurobiological systems hypothesized to be affected by (b) specific types of early adverse experiences, as mediated through (c) potentially modifiable family-based processes, to ultimately influence (d) specific outcomes (Fisher, Stoolmiller, Gunnar, & Burraston, 2007). Intervention trials within this framework can specify causal pathways originating from early adversity that can be modified through parenting to impact underlying child neural systems, which act as an intermediate, mechanistic step in improving behavioral outcomes.

Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1: Extension of the experimental medicine approach for family-based interventions to translational neuroscience research.

To illustrate the application of translational neuroscience within experimental medicine approaches to family-based interventions for addressing adversity, let’s revisit the work of Patterson and colleagues after PMTO’s development and validation. In the 1980s, Patricia Chamberlain, a protégé of Patterson, developed a more intensive family-based approach called Treatment Foster Care Oregon (TFCO1; Eddy & Chamberlain, 2000) to treat conduct disorders in children and adolescents. TFCO, while focusing on the same parenting practices as PMTO, was implemented in a foster home setting. This environment allowed these parenting practices to be emphasized without the ingrained coercive interactions often present in biological families. Once a youth responded to the parenting in the foster home and the birth parents had learned similar strategies (through PMTO-type training), the youth was transitioned back home. TFCO has been rigorously evaluated in several randomized clinical trials and has proven to be a highly effective intervention tool for reducing problem behavior and preventing subsequent delinquency in troubled youth (Leve et al., 2012).

In the 1990s, the TFCO intervention was adapted developmentally downwards to address the specific needs of preschool-aged children in foster care (TFCO-P2; Fisher, Ellis, & Chamberlain, 1999). Similar to TFCO for older children, TFCO-P provided intensive support to foster parents to implement effective parenting practices. To further support preschoolers’ social skills and kindergarten readiness, the program included a playgroup component. This offered children a typical classroom setting to practice self-regulation and early literacy skills. TFCO-P also extended support to birth and adoptive families after the child transitioned out of foster care into a permanent placement.

As TFCO-P was implemented, clinicians observed that some children initially showed limited treatment response, behaving as if they were still in a threatening or neglectful environment. However, after a period that could last several months, many of these children subsequently experienced positive behavioral changes. Anecdotal observations also suggested improvements in developmental functioning (e.g., letter and color recognition, motor skills). These changes were relatively rapid, occurring over weeks or even days, compared to normative development. This led researchers to hypothesize that ongoing dysregulation in a stress regulatory neural system might initially hinder neurocognitive and behavioral development, even in a more responsive and enriching environment. A subsequent collaboration between intervention researchers and developmental neuroscientists (Gunnar, Fisher, & the Early Experience, Stress, and Prevention Network, 2006) identified the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis as a potential mechanism underlying these phenomena. The HPA axis is a neuroendocrine system crucial for restoring the body to homeostatic balance after stress. Its activation triggers a hormonal cascade leading to bodily changes such as energy metabolism and immune system activation (for a detailed discussion on how adverse early experiences can disrupt HPA axis development, see Fisher, Gunnar, Dozier, Bruce, & Pears, 2006). When TFCO-P was being developed, evidence already existed for elevated HPA axis activity in clinical populations and individuals exposed to acute life and occupational stress (Heim & Nemeroff, 2001; Melamed et al., 1999). Furthermore, some research indicated HPA axis alterations in children raised in institutional settings (orphanages) in developing countries (Carlson & Earls, 1997).

However, remarkably, children in institutional care often exhibited diminished, rather than elevated, levels of cortisol (the end product of the HPA cascade)3 (Gunnar & Vazquez, 2001). Initial research involving foster children mirrored these findings, showing similar patterns of cortisol activity to institutionally reared children. Critically, these patterns were most prevalent among foster children with histories of significant neglect (Bruce, Fisher, Pears, & Levine, 2009). This finding was significant for two reasons: first, neglect was a defining characteristic of the orphanages where diminished HPA activity was observed; and second, contrary to common assumptions, neglect is the primary reason children are placed in foster care, surpassing physical and sexual abuse.

TFCO-P researchers developed a conceptual model for the randomized trial of the program, extending the basic coercion theory model to incorporate neurobiological functioning as an underlying mechanism linked to later outcomes (Fisher et al., 2007). As shown in Figure 7.2, this model posits that maltreatment-related alterations in HPA axis functioning, particularly due to neglect, are mediated through parenting practices experienced by the child after entering foster care. By targeting these parenting practices through TFCO-P, it was hypothesized that outcomes such as anxiety and affective disorders, school success, and externalizing behavior would be positively impacted through changes in, specifically increased regulation of, the HPA axis.

Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2: The conceptual model guiding TFCO-P, highlighting the intervention’s mechanism through parenting and HPA axis regulation.

A large-scale randomized clinical trial was conducted over a decade to evaluate this conceptual model (Fisher et al., 2006). The study design included three arms: foster children randomly assigned to TFCO-P, those receiving services as usual (regular foster care – RFC), and a low-income community comparison group (CC) with no history of maltreatment or child welfare involvement. The total sample of 177 was equally distributed across groups (RFC = 60; TFCO-P = 57; CC = 60).

TFCO-P demonstrated numerous positive effects. The intervention was associated with increased stability in foster care placements and fewer placement disruptions compared to RFC (Fisher, Stoolmiller, Mannering, Takahashi, & Chamberlain, 2011). It also increased the likelihood that permanent adoptive placements or reunifications with birth parents would remain stable over time (Fisher, Burraston, & Pears, 2005). Prior research had shown that placement disruptions are common in foster care and often caused by high rates of child problem behavior. In contrast, the TFCO-P trial showed that children receiving the intervention were protected against placement disruption due to problem behavior. Specifically, RFC children had a threshold of six problem behaviors per day (reported by foster parents), beyond which their risk of disruption increased significantly. However, TFCO-P children showed no such threshold effect; children with more than six problem behaviors remained at the same low risk of disruption as those with fewer problems in both groups (Fisher et al., 2011).

TFCO-P also positively impacted attachment-related behaviors. Intervention children were more likely to seek caregivers when distressed, approaching levels observed in the CC group. Conversely, RFC children showed a decreased likelihood of approaching caregivers when distressed over time (Fisher & Kim, 2007).

Cortisol level results were also significant. Children in TFCO-P were more likely to maintain morning cortisol levels comparable to CC children, while RFC children showed a dramatic decrease in morning cortisol over time – a pattern consistent with neuroendocrine dysregulation seen in severely neglected children (Fisher et al., 2007).

Research further explored variables associated with changes in children’s cortisol levels. One analysis revealed that RFC foster parents reported high stress levels managing child problem behavior at baseline, which persisted throughout placement. In contrast, stress levels in TFCO-P foster parents dropped immediately after baseline and remained low. Notably, in the RFC condition, caregiver stress levels were directly and temporally linked to children’s morning cortisol levels: high foster parent stress one day was associated with diminished child cortisol the next morning. This association was absent for TFCO-P children (Fisher & Stoolmiller, 2008).

Another analysis found that placement changes (between foster homes or to permanent placement) were associated with diminished and atypical morning cortisol levels in RFC children. However, cortisol levels remained stable during placement changes for TFCO-P children. This stability may be attributed to TFCO-P’s emphasis on preparing children for transitions and consistent parenting strategies across caregivers, creating a more stable environment even during placement changes (Fisher, Van Ryzin, & Gunnar, 2011).

Evaluating the Evidence: Translational Neuroscience and Future Directions

The TFCO-P randomized clinical trial results offer multiple interpretations. At a practical level, they demonstrate that employing effective parenting techniques can dramatically alter the life trajectories of young foster children, even after significant adversity. The breadth of positive effects, including improved placement stability, permanency, and psychosocial adjustment, is particularly noteworthy. Furthermore, this trial provided early evidence that family-based interventions can improve the functioning of neurobiological systems affected by early adversity. Crucially, an economic analysis during the trial found that TFCO-P’s costs over 12 months were less than those of conventional foster care (Lynch, Dickerson, Saldana, & Fisher, 2014).

While these results strongly support TFCO-P’s efficacy as an intervention tool, the trial provided less conclusive evidence from an experimental medicine perspective. Figure 7.3 summarizes the study results in terms of validating the conceptual model in Figure 7.2. Arrow thickness in Figure 7.3 represents the estimated strength of observed associations. While TFCO-P impacted parenting stress, changes in the specific parenting behaviors outlined in the model were not clearly observed. Similarly, while behavioral adjustment (secure attachment) improved, and cortisol measures suggested a positive intervention effect, the pathway from intervention to behavioral changes did not appear to be mediated through stress neurobiology or caregiving as hypothesized. Indeed, the most robust mediational process observed was the link between caregiver stress managing problem behavior and children’s cortisol levels the following morning.

Figure 7.3.

Figure 7.3: Evidence for the TFCO-P Conceptual Model, with thicker arrows indicating stronger evidence of associations.

These results present a common challenge in family-based intervention research. While demonstrating positive intervention effects on meaningful outcomes is valuable from a policy standpoint, the TFCO-P trial provides less insight into how the intervention works. Furthermore, focusing solely on main intervention effects can obscure variations in individual responses.

To advance the field, three key areas need attention: First, greater effort must be directed towards examining intervention targets. This includes: (1) ensuring interventions have sufficient specificity in their targets, and (2) confirming intervention effectiveness in engaging those targets before large-scale evaluations. Second, evidence of specific neurobiological systems mediating the link between targets and outcomes must be obtained prior to large-scale research. In the TFCO-P study, while the HPA axis was influenced, its mediating role between parenting, HPA function, and child outcomes remains unclear. Third, understanding moderators of individual variability in intervention response is crucial from the outset. Identifying who benefits most and the underlying processes contributing to response variations can enhance overall intervention effectiveness and inform the development of subsequent, supplemental interventions.

Translational neuroscience can significantly contribute to future research. Evidence suggests that some neural systems serve as common pathways between adversity and negative outcomes (Heim, Plotsky, & Nemeroff, 2004). The HPA axis is one example. Furthermore, a growing body of knowledge exists regarding specific neural regions and circuits associated with common phenotypes underlying developmental psychopathology. For instance, individuals with high early adversity exposure often exhibit executive functioning alterations (Pechtel & Pizzagalli, 2011). These alterations can manifest as poor performance on behavioral tests, real-world behaviors like impulsivity, and can be measured through underlying neural circuitry.

Research examining young foster children’s response to corrective feedback exemplifies translational neuroscience’s potential to inform new insights and family-based interventions. A pilot study using a TFCO-P trial subsample revealed intervention effects on an electrophysiological measure of brain activity. RFC children showed limited response on an event-related potential (ERP) measure during a computer task involving corrective feedback after mistakes. This task, a color flanker task, required inhibiting prepotent responses. In contrast, TFCO-P children showed a typical increase in prefrontal electrical activity following corrective feedback (Bruce, McDermott, Fisher, & Fox, 2009). This specific ERP measure, feedback-related negativity, is also diminished in clinical populations with anxiety and depression.

These results highlight a specific neurobehavioral deficiency in young foster children, potentially impacting school and social functioning, which appears malleable through intervention. By leveraging knowledge of narrowly focused behavioral domains and their neural circuitry, interventions can become more precise, efficient, and effective. This precision can address criticisms of family-based prevention and facilitate more scalable and impactful interventions.

Continued research is essential as our understanding of the neurobiological effects of adversity and their relationship to outcomes expands. Beyond stress hormone and executive functioning systems, evidence indicates adversity’s impact on threat monitoring (Tottenham & Sheridan, 2009) and reward/motivation systems (Dillon et al., 2009). Adversity also affects connectivity among these neural systems (Pollak, 2005), suggesting that networks, rather than isolated regions, may be the most effective targets for interventions.

On a positive note, research is providing increasingly detailed insights into the link between specific types of early adversity and alterations in underlying systems (Champagne, 2010). Studies are also exploring familial, extrafamilial, and intraindividual factors that protect against adversity (McCrory, De Brito, & Viding, 2010). Integrating these models with intervention work holds the potential to advance the field significantly, leading to breakthroughs in scientific understanding and improved well-being for the most vulnerable members of society.

Footnotes

1 The approach developed by Chamberlain and colleagues was originally named Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (MTFC), later renamed and trademarked as Treatment Foster Care Oregon (TFCO) in 2015.

2 TFCO-P was initially named Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care for Preschoolers (MTFC-P), and was renamed and retrademarked as Treatment Foster Care Oregon for Preschoolers (TFCO-P) in 2015.

3 It is important to distinguish between two measures of HPA axis function: reactivity (system activation and recovery in response to lab stressors) and diurnal activity (cortisol levels measured throughout the day). Research on institutionally reared children, adoptees, and foster children primarily uses diurnal HPA axis activity measures for practical and ethical reasons.

References

[R1] Bruce, J., Fisher, P. A., Pears, K. C., & Levine, S. (2009). Morning cortisol levels in preschool-aged foster children: Associations with child behavior problems and caregiver stress. Child Development, 80(5), 1417–1436.

[R2] Bruce, J., McDermott, J. M., Fisher, P. A., & Fox, N. A. (2009). Neural responses to corrective feedback in children with histories of раннего adversity. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 1(3), 313–325.

[R3] Capaldi, D. M., DeGarmo, D. S., Patterson, G. R., & Forgatch, M. S. (2002). Contextual risk factors for child antisocial behavior: Mediating and moderating processes. In J. B. Reid, G. R. Patterson, & J. Snyder (Eds.), Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention (pp. 139–160). American Psychological Association.

[R4] Carlson, M., & Earls, F. (1997). Psychological and neuroendocrinological sequelae of early social deprivation in institutionalized children in Romania. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 807, 419–428.

[R5] Champagne, F. A. (2010). Epigenetic influence of social experiences in early life. Epigenetics & Development, 2(5), 408–417.

[R6] Chiang, J. J., Taylor, S. E., & Bower, J. E. (2015). Social relationships and inflammation: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49(2), 267–281.

[R7] Dillon, D. G., Rosso, I. M., Pechtel, P., Dyke, J. P., Strupp, B. J., & Killgore, W. D. S., … & Pizzagalli, D. A. (2009). Early adversity and the human reward system. Biological Psychiatry, 66(11), 991–998.

[R8] Eddy, J. M., & Chamberlain, P. (2000). Treatment foster care for children and adolescents with conduct problems: A review and meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 3(4), 241–262.

[R9] Fisher, P. A., & Berkman, E. T. (2015). Translational neuroscience and the development of interventions for early adversity: A neurobiological perspective. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38, 1–61.

[R10] Fisher, P. A., Burraston, B. O., & Pears, K. C. (2005). The early intervention foster care program: Permanent placement outcomes and correlates of placement disruption. Child Maltreatment, 10(1), 61–72.

[R11] Fisher, P. A., Ellis, B. H., & Chamberlain, P. (1999). Multidimensional treatment foster care for preschool children: Therapist manual. Eugene, OR: Oregon Social Learning Center.

[R12] Fisher, P. A., Gunnar, M. R., Dozier, M., Bruce, J., & Pears, K. C. (2006). Effects of therapeutic interventions for foster preschoolers on diurnal cortisol activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 31(7), 920–932.

[R13] Fisher, P. A., & Kim, H. K. (2007). Foster children’s developing relationships with caregivers: Attachment patterns and caregiving system functioning. Infant and Child Development, 16(1), 77–90.

[R14] Fisher, P. A., & Stoolmiller, M. (2008). Foster caregiver stress moderates the association between foster children’s problem behavior and morning cortisol levels. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33(4), 537–545.

[R15] Fisher, P. A., Stoolmiller, M., Gunnar, M. R., & Burraston, B. O. (2007). Examining the association between foster care placement history and diurnal cortisol activity in preschoolers using growth-curve modeling. Child Development, 78(6), 1823–1837.

[R16] Fisher, P. A., Stoolmiller, M., Mannering, A. M., Takahashi, K., & Chamberlain, P. (2011). Problem behavior, therapeutic foster care, and placement disruption: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(1), 117–127.

[R17] Fisher, P. A., Van Ryzin, M. J., & Gunnar, M. R. (2011). Stability of diurnal cortisol during foster care placement changes: Associations with intervention and placement history. Development and Psychopathology, 23(1), 237–249.

[R18] Gunnar, M. R., Fisher, P. A., & The Early Experience, Stress, and Prevention Network. (2006). Bringing basic research on early experience and stress neurobiology to bear on preventive interventions for neglected and maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology, 18(3), 651–677.

[R19] Gunnar, M. R., & Vazquez, D. M. (2001). Stress neurobiology and developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 1. Theory and method (pp. 533–577). Wiley.

[R20] Heim, C., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2001). The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: Preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry, 49(12), 1023–1039.

[R21] Heim, C., Plotsky, P. M., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2004). Early adverse experiences and the developing brain: Evidence from animal and human studies. Molecular Psychiatry, 9(12), 1021–1039.

[R22] Insel, T. R., Cuthbert, B. N., Garvey, M. A., Heinssen, R. K., Pine, D. S., Quinn, K. J., … & Wang, P. S. (2013). Research domain criteria (RDoC): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(7), 748–755.

[R23] Kazdin, A. E. (1997). Parent management training: Evidence, outcomes, and issues. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(10), 1349–1356.

[R24] Leve, L. D., Kim, H. K., Johnson, P. S., Fisher, P. A., Chamberlain, P., & Hay, J. S. (2012). Outcomes of treatment foster care for adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(5), 791–800.

[R25] Lynch, F. L., Dickerson, J., Saldana, L., & Fisher, P. A. (2014). Cost-effectiveness of therapeutic foster care for young children: Results from a randomized trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(3), 487–495.

[R26] McCrory, E. J., De Brito, S. A., & Viding, V. (2010). Research review: The neurobiology and genetics of maltreatment and adversity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(10), 1079–1095.

[R27] Melamed, S., Kushnir, T., Shifron, G., Ribak, J., & Maltz, M. (1999). Burnout and risk of cardiovascular disease: Evidence, possible causal paths, and promising research directions. Psychological Bulletin, 125(1), 43–63.

[R28] Patterson, G. R. (1982). Coercive family process. Castalia.

[R29] Patterson, G. R., Chamberlain, P., & Reid, J. B. (1982). Parent management training. Behavior Therapy, 13(5), 638–650.

[R30] Patterson, G. R., DeBaryshe, B. D., & Ramsey, E. (1989). A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychological Association.

[R31] Patterson, G. R., Reid, J. B., & Dishion, T. J. (1992). Antisocial boys. Castalia.

[R32] Patterson, G. R., Reid, J. B., & Eddy, J. M. (2002). A brief history of research at the Oregon Social Learning Center. In J. B. Reid, G. R. Patterson, & J. Snyder (Eds.), Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention (pp. 3–22). American Psychological Association.

[R33] Pechtel, P., & Pizzagalli, D. A. (2011). Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective functioning: Implications for depressive disorders. Psychopharmacology, 214(1), 55–70.

[R34] Pine, D. S., & Leibenluft, E. (2015). Experimental medicine approaches to elucidate childhood psychopathology. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(2), 101–102.

[R35] Pollak, S. D. (2005). Early adversity and the development of emotion recognition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 70(2), vii–viii, 1–149.

[R36] Shonkoff, J. P., & Fisher, P. A. (2013). Translating neuroscience to advance early childhood policy and practice. Child Development, 84(1), 69–84.

[R37] Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., McGuinness, G. A., … & Wood, D. L. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246.

[R38] Tottenham, N., & Sheridan, M. A. (2009). Threat-related activity in the amygdala is associated with early caregiving experiences. Developmental Science, 12(3), 399–406.

[R39] Tyrka, A. R., Burgers, D. E., Philip, N. S., Price, L. H., & Carpenter, L. L. (2013). Child abuse and neglect and telomere length: A systematic review. Biological Psychiatry, 74(1), 5–18.