Introduction

In healthcare professional education, the bedrock of effective teaching lies in understanding and applying adult learning theories. These theories offer conceptual frameworks that explain how adults acquire knowledge, skills, and attitudes, leading to changes in behavior, performance, and overall potential. For healthcare educators striving to optimize their instructional methods, grasping these theories is not just beneficial—it’s essential.

The term “andragogy,” distinguishing adult learning from child-centered pedagogy, highlights the unique characteristics of adult learners. Coined by Alexander Kapp and popularized by Malcolm Knowles, andragogy emphasizes that adults bring a wealth of experience, distinct motivations, and specific learning needs to educational settings. This is particularly relevant in healthcare, where professionals build upon existing knowledge and practical experiences to enhance their expertise. While the term andragogy isn’t without its critics, Knowles’ principles have significantly shaped teaching strategies tailored for adult learners, forming the foundation for much of modern healthcare professional education.

Understanding adult learning theories is paramount for several compelling reasons. Firstly, these theories are the cornerstone of evidence-based educational practice. Just as clinical practice relies on research and data, so too should educational strategies. Secondly, a comprehensive knowledge of diverse learning theories empowers educators to select the most effective instructional strategies, define clear learning objectives, and design robust assessment and evaluation methods. This selection should be context-aware, considering the specific learning environment and the needs of the learners. Thirdly, integrating learning theories allows educators to connect subject matter with student comprehension, ultimately fostering improved learning outcomes. Finally, by recognizing the influence of individual learning differences through the lens of learning theories, educators can avoid bearing sole responsibility for every aspect of student learning, acknowledging the complex interplay of factors that contribute to educational success. Educational psychology provides a rich toolkit of adult learning theories, and healthcare educators must leverage this understanding to justify and refine their teaching activities, grounding them in solid theoretical foundations relevant to their specific learning environments.

Effective pedagogies should be integral across the spectrum of healthcare professional education, from undergraduate and graduate programs to continuing professional development (CPD). However, a gap often exists between theoretical understanding and practical implementation. Learning pedagogies are frequently underutilized in the design and delivery of healthcare education programs, whether at the undergraduate, graduate, or CPD level. This disconnect can hinder the effectiveness of educational interventions and limit the potential for enhanced student learning.

This article aims to bridge this gap by providing a synthesized and accessible overview of adult learning theories and their practical applications in healthcare professional education. We present specific examples illustrating how these theories can be employed in real-world settings, offering healthcare educators instant teaching tools – readily understandable theoretical frameworks and practical examples – to enhance their teaching. Our goal is to empower educators to recognize the significance of learning theories, enabling them to select and apply the most appropriate theory and associated educational activities for their unique learning environments and contexts, ultimately leading to enriched educational programs and improved learning experiences for healthcare professionals.

Methods

A thorough literature review, conducted initially in 2015 and updated in 2016, served as the foundation for this synthesis. We utilized prominent academic databases including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and ERIC to identify relevant publications. The search strategy combined terms such as “education theory,” “educational model,” “learning theory,” “teaching method,” “medical education method,” “psychological theory,” and “healthcare education” (and variations thereof). Boolean operators (AND/OR) were employed to refine search results across databases. Keywords were prioritized over MeSH terms to ensure consistency, and searches spanned the entire publication content, not limited to titles or abstracts.

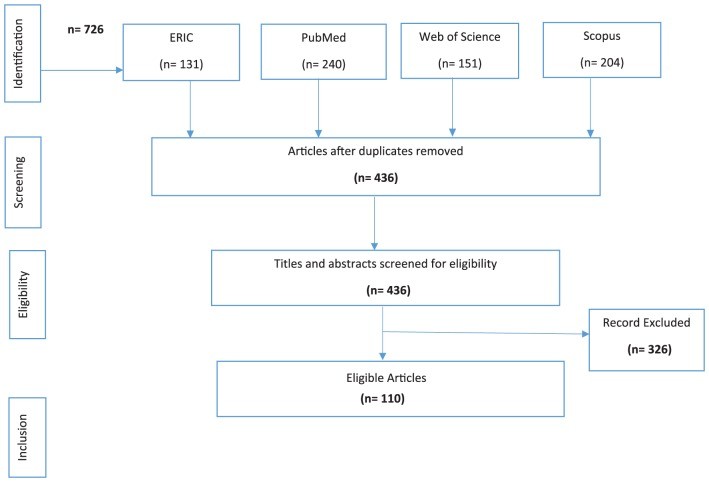

Inclusion criteria encompassed English-language books and articles published between January 1999 and October 2016, available in full electronic format, focusing on the identification, categorization, explanation, or application of learning theories in undergraduate, graduate, or CPD healthcare professional education. Exclusion criteria removed editorials, letters, opinion pieces, commentaries, essays, preliminary notes, duplicate publications, theses, dissertations, and conference abstracts. The article selection process adhered to the PRISMA flow chart methodology, as depicted in Figure 1 of the original article. Table 1, “Categorization of learning theories used in health professional education programs,” synthesizes the findings, including articles highlighting learning theory categorizations and applications while excluding redundancies.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Chart Detailing Article Selection Process for Literature Review

To ensure a comprehensive review, we manually examined the reference lists of selected articles and contacted authors to gather further recommendations on relevant literature. Database alerts were also set up to capture newly published articles, ensuring the inclusion of up-to-date references.

The identified articles were compiled, synthesized, and summarized in Table 1. While not a systematic review, this approach aimed to present learning theories relevant to healthcare professional education in an accessible format. Data extracted from the selected articles included learning theory categorizations, definitions, limitations, and applications in healthcare professional education.

For categorizing learning theories, we adopted the framework proposed by Taylor and Hamdy, recognized for its contemporary and widely cited review of key learning theories within medical education. We expanded upon their work to incorporate constructivism as a distinct category, aligning with its recognition in other literature. The “Results” section presents a narrative and tabular summary of each theory, including healthcare education application examples and critical evaluations derived from the literature.

Results

Adult learning theories, as synthesized from the literature, can be broadly categorized into instrumental, humanistic, transformative, social, motivational, reflective, and constructivist learning theories. These categories, rooted in psychological learning theories, are influenced by constructivist views of andragogy, which emphasize learning as a process of building new knowledge upon existing foundations. This constructivist perspective explains the overlapping principles observed across some theories, often appearing as logical extensions and developments of one another.

Instrumental Learning Theories

Instrumental learning theories emphasize the learner’s individual experience and include behavioral theories, cognitivism, and experiential learning.

Behavioral Theories

Behavioral theories focus on how environmental stimuli lead to changes in individual behavior, with learning being one such consequence. Positive consequences, or reinforcers, strengthen behaviors and enhance learning, whereas negative consequences, or punishers, weaken them. Within this paradigm, educators control the learning environment to elicit specific responses, embodying a teacher-centered approach.

In healthcare education, behavioral theories find application in skill-based training and standardized procedures. For instance, in an undergraduate human physiology lab, students follow detailed protocols for experiments. Clicker questions provide immediate feedback, indicating adherence to instructions. Summative points, graded on a scale from A to F, serve as positive or negative reinforcement, shaping behavior towards accurate measurements and reporting. Similarly, in pharmacy education, behavioral theories underpin frameworks like the Foundation and Advanced Pharmacy Frameworks, which measure clinical performance in CPD settings. However, behavioral theories are criticized for overlooking the social aspects of learning and for the challenges in standardizing learning outcomes, potentially limiting their applicability in complex healthcare scenarios.

Cognitivism

Cognitivism shifts focus to the learner’s internal mental environment and cognitive structures, rather than external contexts. Cognitive learning theories emphasize mental processes like insight, information processing, perception, reflection, metacognition, and memory in facilitating learning. Learning, in this view, primarily occurs through formal education, via verbal or written instructions and demonstrations, resulting in the accumulation of explicit and identifiable knowledge.

Concept mapping in medical education exemplifies cognitivism. Concept maps help students recall foundational concepts and understand their intricate relationships. In nursing education, simulation-based experiences leverage cognitivism, allowing learners to internally control knowledge construction by using prior knowledge to create new understanding. Despite its utility, cognitivism is critiqued for its association with positivist assumptions, considering knowledge abstract and classroom-bound, thus underestimating real-world learning dimensions and the development of essential healthcare professional attitudes rooted in practical experience.

Experiential Learning

Experiential learning posits that learning and knowledge construction are facilitated through interaction with authentic environments. Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, comprising concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation, highlights learning as a cyclical process of apprehension, comprehension, intention, and extension.

Experiential learning is highly valued in healthcare professional education, emphasizing practical skill development in real-life contexts. It is used to design learning strategies for building theoretical knowledge and professional competencies across undergraduate, graduate, and CPD programs. Pharmacy education utilizes experiential learning to foster lifelong learning and adaptability in practical environments, encouraging practitioners to reflect on experiences and make clinical judgments. However, this theory is criticized for focusing predominantly on individual knowledge development, neglecting the social context of learning and its influence. Kolb’s four-phase cycle, while influential, may oversimplify the complex and often fragmented nature of real-world learning.

Humanistic Theories or Facilitative Learning Theories (Self-Directed Learning)

Humanistic theories, emerging in the 1960s, prioritize human freedom and dignity in achieving full potential. They advocate for self-directed learning, where adults plan, manage, and assess their learning to achieve self-actualization, fulfillment, motivation, and independence. Learning becomes student-centered and personalized, with educators acting as facilitators.

Self-directed learning is applied in medical and healthcare professional education through technology-based simulations, problem-solving, and role-play, fostering self-direction and self-assessment. This approach is particularly useful for learning to manage complex patient cases. In pharmacy CPD programs, self-directed learning supports pharmacists’ lifelong learning journeys. Critics argue that humanistic theories overlook the influence of culture, society, and institutional structures on learning and underemphasize collaborative learning approaches.

Transformative Learning Theories (Reflective Learning)

Transformative learning theories focus on fundamentally changing meanings, contexts, and long-held beliefs. Learners are empowered to question and challenge their assumptions, or “frames of reference,” as termed by Mezirow. Learning occurs when new knowledge integrates with existing knowledge, prompting learners to challenge and modify their “meaning schemes.”

Transformative learning involves experiencing a problem, reflecting on prior perspectives, engaging in critical self-reflection, and acting based on this reflection, leading to a transformation of meaning. Critical incident analysis and group discussions in medical education exemplify transformative learning, encouraging learners to reflect on assumptions, share ideas, and examine reflective practices. Pharmacy education incorporates transformative and critical reflection strategies to cultivate self-reflective and metacognitive skills, enabling students to provide tailored patient care and adapt to evolving healthcare systems. However, transformative learning theories are criticized for overemphasizing critical reflection at the expense of emotions and context. They may also overlook unconscious transformation and the impact of long-term memory on behavior, and lack clarity on factors that facilitate perspective revision.

Social Theories of Learning (Zone of Proximal Development, Situated Cognition, Communities of Practice)

Social learning theories integrate behavior modeling with cognitive learning, enhancing task performance understanding. They emphasize social interaction, personal context, community, and desired behavior as key learning facilitators. Observation and modeling are fundamental, with educators responsible for providing supportive environments and clarifying expected behaviors.

In medical education, social learning theories are evident in practical training where trainee physicians learn by observing and emulating preceptors. Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), situated cognition, and Communities of Practice (CoP) are key concepts. CoP theory is explored across medical, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, nursing, pharmacy, and surgical education. Social theories, however, are critiqued for neglecting learners’ emotional and mental states and individual differences in learning abilities. They may also underaccount for biological, neurophysiological, cultural, linguistic, and historical factors shaping learning experiences.

Motivational Models (Self-Determination Theory, Expectancy Valence Theory, Chain of Response Model)

Motivational models underscore the role of motivation and reflection in adult learning. Self-determination theory focuses on intrinsic motivation, expectancy valence theory incorporates the expectation of success, and the chain of response model highlights self-evaluation, learner attitude, and the importance of goals.

While not always explicitly integrated into medical curricula, motivational theories are implicitly present, with student motivation often an outcome of implemented educational strategies. Intrinsic motivation is enhanced by meeting student needs, fostering positive relationships, and providing constructive feedback. Limited literature explores pharmacy student motivation and its connection to academic performance or learning environments. Motivational models are sometimes criticized for an overemphasis on extrinsic motivation driven by assessments, rather than using assessments as feedback tools to enhance learning.

Reflective Models (Reflection-on-Action and Reflection-in-Action)

Reflective models, as proposed by Schön, include reflection-on-action (evaluating processes after they occur) and reflection-in-action (reflecting during the activity). Reflection facilitates knowledge testing through investigation, helping students make sense of complex situations and learn from practical experience. Reflective learning varies with individual reflection abilities and requires supportive environments and educator encouragement. Structured guides and constructive feedback are essential for learners.

Structured reflection in medical education enhances student competence and clinical practice learning. Pharmacy education applies reflective learning to integrate theory and practice, enhancing critical thinking, problem-solving, and self-directed learning. Reflective models are crucial in healthcare education for developing reflective practice and learning systems that advance learner knowledge and skills. However, they are criticized for lacking elaboration on the psychological realities of reflection, unclear distinctions between reflection types, and insufficient clarification of the reflective process itself, including the time dimension in decision-making post-reflection.

Constructivism (Cognitive Constructivism and Socio-Cultural Constructivism)

Constructivism, both as epistemology and learning theory, explains knowledge and meaning-making. Cognitive constructivists (Ausubel, Piaget) and socio-cultural constructivists (Vygotsky) emphasize knowledge construction through interactions between prior knowledge, social interactions, and environmental factors. Knowledge is actively constructed and relative to the learner’s environment. Constructivism holistically approaches pedagogy, considering internal cognitive mechanisms, participation, and social interaction.

Constructivist approaches, combined with Kolb’s model, underpin experiential learning, emphasizing action-based and outcome-based learning. Medical education strategies like group discussions, journal clubs, and portfolio development are guided by constructivism. Vygotsky’s ZPD is applied through teacher demonstrations followed by scaffolded independent practice. Pharmacy education encourages students to construct their own knowledge and apply concepts in real situations. However, constructivism is criticized for leaning towards epistemological relativism, potentially leading to a view that absolute truth is culturally dependent. Concerns are also raised about its quasi-religious aspects, potential neglect of passive learning and memorization, and overemphasis on the learning environment at the expense of the individual mind.

Categorization of Learning Theories Used in Health Professional Education Programs

Table 1 provides a concise summary of these learning theories, detailing their originators, applications in healthcare professional education (undergraduate, graduate, CPD), and critical evaluations. This summary serves as an instant teaching tool, enabling healthcare educators to make informed decisions regarding instructional strategies, learning objectives, and assessment approaches, ultimately enhancing student learning experiences. The table highlights applications in healthcare education, such as behavioral theories informing clinical performance frameworks, cognitivism guiding concept map design, humanistic theories underpinning CPD programs, reflective learning enhancing clinical competence, and constructivism shaping group discussions and portfolio development.

Discussion

Healthcare professional educators, often drawn from fields like pharmacy, medicine, nursing, and dentistry, may not have formal training in education. Many, particularly in pharmacy, lack formal pedagogical training, developing teaching skills primarily through experience. Supporting novice nurse educators transitioning from clinical roles is crucial, involving expertise exchange, resource sharing, and professional development to address challenges and enhance educator satisfaction and student learning experiences.

Ideally, healthcare educators should be proficient in various learning theories to select the most appropriate approach based on educational setting, learner characteristics, teaching purpose, resource availability, and context. Benner et al. emphasize the significance of theoretical considerations, arguing that theory informs and is informed by practice. However, learning theories are inconsistently implemented in healthcare education program design and practices, potentially leading to variable outcomes. In the UK, structural disconnects between the NHS and higher education institutions contribute to this gap, causing theory-practice-research fragmentation. In Canada and potentially elsewhere, accreditation bodies may dictate educational agendas, with varying emphasis on learning theory in accreditation standards.

A systematic review of higher nursing education highlighted the need for pedagogical training for nursing teachers, emphasizing specialty-pedagogy transitions and deeper pedagogical knowledge. A scoping review across health science disciplines confirmed clinician teachers’ need for faculty development workshops focused on common learning theories and teaching methods in graduate and undergraduate education.

Gonczi notes that preceptors in healthcare education often lack educator development, yet are responsible for student learning in practice settings. University-practice site partnerships are crucial for enhancing student learning and preceptor development, building organizational capacity for academics and practitioners to better serve students and teaching pedagogies. Moss et al. advocate for advancing graduate healthcare education pedagogy through research into its influence on curriculum components: content, delivery, and assessment. Explicitly explaining the benefits of graduate pedagogies, such as practice enhancement and professional development, is also vital.

Conclusions

This article provides healthcare professional educators with a readily accessible summary of adult learning theory categorizations, applications, and the crucial link between educational practice and learning theory. By considering the nature of healthcare knowledge and the philosophical underpinnings of healthcare professional education beyond pragmatic perspectives, educators can restructure curricula, instructional strategies, learning objectives, and evaluation approaches. This deeper theoretical consideration in healthcare professional education will ultimately enrich student learning experiences and create more effective healthcare professionals. These summarized theories serve as instant teaching tools, providing a practical and accessible resource for educators to enhance their teaching practice immediately.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Qatar University for funding and Dr. Ahmed Awaisu, College of Pharmacy, Qatar University, for his valuable feedback. This work is part of Banan Abdulrzaq Mukhalalati’s PhD research, sponsored by Qatar University and awarded by the University of Bath, UK.

Footnotes

Funding: This research was not financially supported beyond institutional funding from Qatar University for the corresponding author’s PhD research.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions: AT, as PhD supervisor, contributed to the work’s conception, intellectual content revision, final approval, and integrity confirmation.

ORCID iD: Banan Abdulrzaq Mukhalalati https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0049-8879