Patients diagnosed with glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer, face a grim prognosis and endure a significant decline in neurological function, coupled with the harsh side effects of treatment. Early integration of palliative care alongside oncology treatment is widely recognized for its benefits. However, the utilization of palliative care services remains surprisingly low for these patients. This article delves into a quality improvement (QI) project designed to explore the practicality, value, and effectiveness of employing a tailored palliative care screening tool. The aim was to enhance the identification and referral of glioblastoma patients in outpatient settings who could benefit from palliative care. Conducted over a 10-week period, this QI project focused on implementing and evaluating a glioma-specific palliative care screening tool within routine outpatient visits. Healthcare providers were instructed to utilize this tool during each consultation with eligible patients—adults aged 18 and over diagnosed with World Health Organization (WHO) grade IV glioma, returning for a scheduled brain MRI evaluation at the neuro-oncology clinic. The project meticulously tracked screening rates, discussions about palliative care, and actual referral rates. Out of 530 eligible patients visiting the clinic during the study period, the screening tool was accessible for 433. Ultimately, 56% (294 out of 530) of patients underwent screening. Among those screened, 9% (27 patients) were identified as potential candidates for palliative care referral, scoring 5 or higher on the screening tool. Of these 27 patients, 63% (17) engaged in discussions about palliative care, and remarkably, 71% (12) of those who had these discussions were subsequently referred to a palliative care provider. The findings strongly suggest that incorporating a glioma palliative care screening tool into outpatient visits is a viable strategy to highlight palliative care needs and effectively increase referrals to these essential services.

High-grade gliomas, notably glioblastoma (WHO grade IV), represent the most prevalent primary malignant tumors of the central nervous system (Ostrom et al., 2017). Patients with glioblastoma typically have a median survival of just 12 to 15 months (Alcedo-Guardia, Labat, Blas-Boria, & Vivas-Mejia, 2016). Throughout their illness, they often experience considerable neurological deterioration, imposing a substantial burden on both patients and their caregivers. The palliative care requirements for glioblastoma patients are particularly intricate due to the significant symptom burden arising from functional, cognitive, and communicative impairments. Common symptoms associated with disease progression include drowsiness, cognitive deficits, aphasia, motor weakness, seizures, and personality alterations. Furthermore, patients may suffer from side effects of chemotherapy and radiation, such as nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and further cognitive decline (Walbert & Khan, 2014).

A comprehensive literature review by Walbert (2014) on palliative care, hospice, and end-of-life care in neuro-oncology revealed that patients with high-grade gliomas often receive less palliative care compared to individuals with other cancers, despite their high symptom burden. This underutilization can be attributed to several factors: (1) a common misconception among patients and families that palliative care is only appropriate at the very end of life (Perrin & Kazanowski, 2015), (2) provider perceptions that palliative care is synonymous with hospice, potentially diminishing hope (Hui et al., 2015), and (3) crucially, a lack of provider knowledge or consensus on the criteria for palliative care referral.

A growing body of evidence underscores the importance of integrating early palliative care into the management of advanced cancer patients. Studies have consistently shown that early palliative care is associated with improved quality of life, reduced mood disturbances (like depression and anxiety), and decreased healthcare costs (Adelson et al., 2017; Davis, Temel, Balboni, & Glare, 2015; El-Jawahri et al., 2016; Grudzen et al., 2016; Nakajima & Abe, 2016; Salins, Ramanjulu, Patra, Deodhar, & Muckaden, 2016; Temel et al., 2016; Vanbutsele et al., 2018). Despite increasing awareness of the benefits of early palliative care in advanced cancers, literature reviews highlight a persistent lack of understanding among both patients and healthcare providers regarding the appropriate timing and application of palliative care. Provider referral practices are identified as a major impediment to palliative care access (Kumar et al., 2012). Research suggests that employing screening tools to identify patients who would benefit from palliative care can significantly enhance timely referrals. A study by Begum (2013) demonstrated that using a screening tool reduced the proportion of patients not referred to palliative care from 68% to just 16% within a four-month period.

Clinical guidelines from organizations like the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) advocate for outpatient oncology programs to offer palliative care resources to cancer patients experiencing significant physical and psychosocial symptom burden (Ferrell et al., 2017). Similarly, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend routine screening for palliative care referral for all advanced cancer patients (Swarm & Dans, 2018). However, a study by Albizu-Rivera and colleagues (2016) indicated that only a small fraction (10%) of NCCN member institutions utilize these guidelines for palliative care screening, and many respondents expressed uncertainty about referral criteria and timing. The adoption of standardized needs assessment tools is crucial to promote the role of palliative care in oncology. This QI project directly addressed this need by implementing a palliative care screening tool to increase both screening rates and referrals for glioblastoma (WHO grade IV) patients within an outpatient neuro-oncology clinic.

Project Objectives

This project aimed to evaluate the feasibility, value, and effectiveness of implementing a palliative care screening tool for glioblastoma (WHO grade IV) patients returning to the Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center (PRTBTC) at Duke Cancer Institute (DCI) for follow-up evaluations.

The primary objective was to assess the feasibility of using a palliative care screening tool. This was measured by determining the proportion of eligible WHO grade IV malignant glioma patients returning to PRTBTC for follow-up MRI who were screened using the glioma palliative care screening tool.

The secondary objective focused on the value of the screening tool, specifically the proportion of patients scoring 5 or higher on the tool who subsequently had a discussion about palliative care.

The tertiary objective was to assess the effectiveness of the screening tool, measured by the proportion of patients referred to palliative care among those who had a palliative care referral discussion.

Methodology

This QI project was designed to investigate the feasibility, value, and effectiveness of a palliative care screening tool in improving outpatient palliative care screening and referrals for glioblastoma (WHO grade IV) patients. The project underwent formal evaluation using a QI checklist and was deemed exempt from institutional review board oversight.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify palliative care screening tools specifically designed for neuro-oncology patients. However, no such tool was found. A simplified palliative care screening tool (Glare, Semple, Stabler, & Saltz, 2011), originally developed for general outpatient oncology patients based on NCCN palliative care screening criteria, was identified and adapted for this project. This tool consists of five key screening items: (1) presence of metastatic or locally advanced cancer, (2) functional status based on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, (3) presence of serious complications from advanced cancer typically indicating a prognosis of fewer than 12 months, (4) presence of serious comorbid diseases associated with poor prognosis, and (5) presence of palliative care problems. A total score of 5 or more was recommended as a threshold for referral.

This screening tool was adapted for brain tumor patients in consultation with the neuro-oncology team at PRTBTC (Appendix A). Given that glioblastoma (WHO grade IV) is already an advanced disease and extracranial metastases are rare, “progressive disease at the current visit” was deemed equivalent to “metastatic or locally advanced cancer” (item 1). For functional status (item 2), while the original tool used ECOG criteria (Glare et al., 2011), PRTBTC utilizes the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS). The adapted tool included a direct conversion between ECOG and KPS. The item regarding serious complications of cancer (item 3) was clarified with examples like “metastatic disease to the spine,” later expanded to include “progression of disease more than twice,” or “new multifocal disease.” Examples for comorbid diseases (item 4) were initially listed as moderate-to-severe congestive heart failure (CHF), stroke, dementia, renal disease, liver disease, pulmonary embolism, bowel perforation, cerebral edema, and obstructive hydrocephalus. These were further augmented to include a history of moderate-to-severe CHF, stroke, cognitive deficit, renal disease, liver disease, pulmonary embolism, bowel perforation, cerebral edema, obstructive hydrocephalus, cytopenia, or any new active problem requiring intervention or hospital admission.

A questionnaire (Appendix B) was created to collect patient data including age, sex, diagnosis, palliative care discussions and referrals, and the destination of referral (Duke palliative care or local oncologist). It also included a section to document reasons for not discussing or making a palliative care referral when indicated.

Prior to project launch, informational sessions were conducted for clinical staff at PRTBTC, including neuro-oncologists, nurse clinicians, clinic nurses, advanced practice providers (APPs), and certified medical assistants (CMAs).

CMAs were responsible for providing the glioma palliative care screening tool (Appendix A) and provider questionnaire (Appendix B) to APPs for eligible patients. APPs then conducted palliative care needs screening during patient examinations and medical history review. If the screening tool indicated a referral need (score ≥ 5), the APP discussed palliative care referral with the attending physician and the patient. Referrals were made only with the agreement of both the attending physician and the patient. Local patients were referred to Duke palliative medicine, while for out-of-state patients, a recommendation for palliative care referral to their local oncologist was made. APPs completed the questionnaire (Appendix B) after screening and referral decisions.

Setting and Participants

The QI project was carried out at the PRTBTC at DCI, a specialized tertiary outpatient neuro-oncology clinic in Durham, North Carolina, serving adult patients with primary brain and spinal tumors.

The study population comprised patients aged 18 years or older with a confirmed diagnosis of WHO grade IV malignant glioma (glioblastoma or gliosarcoma), proficient in English, and returning to PRTBTC for routine follow-up with a new brain MRI. Patients visiting for initial evaluations, new patient consultations, or those already referred to palliative care were excluded.

The primary providers involved were 10 board-certified APPs (7 nurse practitioners, 3 physician assistants), with six having over 5 years of experience. PRTBTC APPs collaborate closely with supervising neuro-oncologists and communicate patient care needs with local oncology teams. Physicians, fellows, residents, and medical students also participated in screening and questionnaire completion.

Measurements and Analysis

The analyses for this QI project were primarily descriptive. The main outcome measure was the proportion of eligible patients screened for palliative care needs using the glioma palliative care screening tool among those returning for follow-up MRIs over the 10-week period. This was calculated by dividing the number of patients screened by the total number of eligible patients.

The questionnaire (Appendix B) collected data on palliative care discussions. The second outcome, the proportion of screened patients who had a palliative care referral discussion, was determined by dividing the number of patients who discussed referral by the number of patients scoring 5 or higher on the screening tool.

The third objective, effectiveness, was assessed by the referral rate. This was measured by the proportion of patients referred to Duke palliative medicine or recommended for local palliative care referral among those who had a palliative care discussion.

Project Results

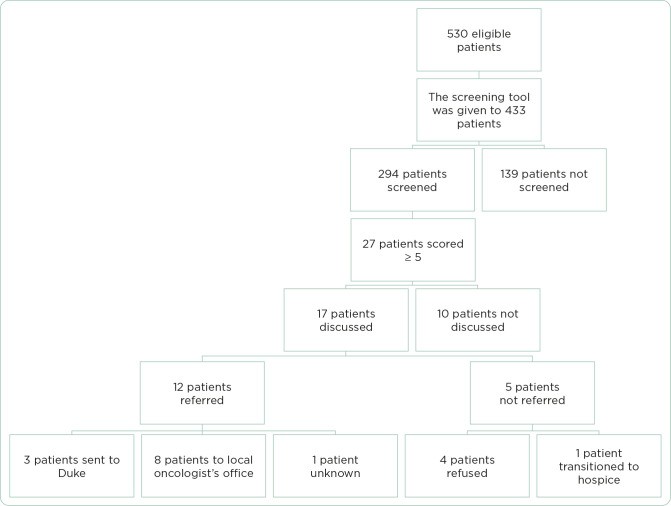

During the 10-week implementation (September–December 2018), 530 patients were identified as eligible for screening. Figure 1 illustrates the screening, discussion, and referral outcomes. The screening tool was provided to providers for 433 of these patients. In the initial 17 days, CMAs did not distribute the tool for 97 eligible patients. Of the 433 patients for whom the tool was available, 294 (68%) were screened (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Palliative care referral outcomes.

Table 1. Project Outcomes.

| Outcome | Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of eligible patients screened | 294/530 (56%) | 51%–60% |

| Proportion of eligible patients screened among those for whom the certified medical assistant provided the form to the APP | 294/433 (68%) | 64%–72% |

| Proportion of screened patients with score ≥ 5 | 27/294 (9%) | 5.9%–12.5% |

| Proportion of patients with score ≥ 5 who had a palliative care discussion | 17/27 (63%) | 42%–81% |

| Proportion of patients with score ≥ 5 who were referred to a palliative care consult | 12/27 (44%) | 25%–65% |

| Proportion of patients with referral among those with a palliative care discussion | 12/17 (71%) | 44%–90% |

The screened patient group was predominantly male (60%) and had a Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) of 70% or higher (47%). Nearly half (45%, n = 131) had a zero score on the NCCN Distress Thermometer. The majority (53%, n = 177) were between 46 and 65 years old (Table 2).

Table 2. Patient Demographics.

| Demographics Category | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 177 (60%) |

| Female | 109 (37%) |

| Unknown | 8 (3%) |

| Age | |

| 18–25 | 18 (6%) |

| 26–35 | 39 (13%) |

| 36–45 | 49 (17%) |

| 46–55 | 84 (29%) |

| 56–65 | 71 (24%) |

| 66–75 | 21 (7%) |

| > 75 | 10 (4%) |

| Unknown | 2 (1%) |

| Karnofsky Performance Status | |

| 90%–100% | 133 (45%) |

| 70%–80% | 123 (42%) |

| 50%–60% | 35 (12%) |

| 30%–40% | 3 (1%) |

| 10%–20% | 0 (0%) |

| NCCN Distress Thermometer score | |

| 0 | 131 (45%) |

| 1 | 35 (12%) |

| 2 | 26 (9%) |

| 3 | 21 (7%) |

| 4 | 17 (6%) |

| 5 | 19 (6%) |

| 6 | 8 (3%) |

| 7 | 8 (3%) |

| 8 | 4 (1%) |

| 9 | 2 (1%) |

| 10 | 3 (1%) |

| Unknown | 20 (7%) |

Regarding feasibility (aim 1), 56% (294/530) of eligible patients were screened for palliative care needs using the glioma palliative care screening tool.

For value (aim 2), 9% (27/294) of screened patients scored 5 or higher, indicating a need for palliative care consideration. Among these 27 patients, 63% (17/27) had a palliative care discussion. Of the 10 patients who did not have a discussion, reasons included focus on treatment planning (5), attending physician disagreement (3), and unspecified reasons (2).

Assessing effectiveness (aim 3), 71% (12/17) of patients who had a palliative care discussion were referred to palliative care. Of these 12 referrals, three were to Duke palliative care, eight were recommendations for local palliative care, and one lacked specific documentation. Among the five patients not referred, four refused, and one was referred to hospice.

APPs conducted the majority of screenings (89%, 262/294), with additional screenings by fellows, residents, medical students, and one attending physician.

Discussion

Patients with high-grade gliomas, particularly glioblastoma (WHO grade IV), suffer from significant neurological symptoms and treatment-related side effects. The benefits of integrating early palliative care with oncology care are well-established. Given the complex symptom burden in these patients, timely palliative care referral is critical.

Historical data from 2018 showed an average of six brain tumor patients per 10-week period were referred to Duke palliative care. A pilot study on early palliative care integration for glioblastoma patients showed approximately two referrals per 10 weeks. This QI project resulted in 12 palliative care referrals within 10 weeks, with 56% (294/530) of eligible patients screened. This demonstrates that integrating a palliative care screening tool is feasible, raises awareness of palliative care needs, and increases referrals.

Initial challenges included tool distribution, with CMAs not providing tools for 18% of patients in the first 17 days. This was resolved by APPs and clinical staff distributing tools directly. Screening rates could be further improved by integrating the tool into the electronic medical record system with automated alerts for scores of 5 or higher.

This project highlighted the role of a multidisciplinary team, particularly APPs who conducted 89% of screenings and initiated palliative care discussions. APPs can be pivotal in integrating palliative care into standard oncology care.

While extensive searches found no validated screening tool specifically for high-grade glioma, the adapted tool (Glare et al., 2011) was carefully chosen and modified in consultation with neuro-oncology experts. A limitation is the lack of formal validation for this glioma-specific adapted tool. However, the original tool has been validated for broader outpatient cancer populations, with an inpatient version also validated (Glare & Chow, 2015).

Despite 27 patients scoring high enough for referral, 10 did not have palliative care discussions. In five of these cases, providers prioritized treatment planning over palliative care. Time constraints and clinical workload can detract from palliative care focus. Integrating palliative care visits with oncology appointments could improve integration.

Of the 17 patients discussed for referral, four refused palliative care. This may stem from misunderstandings about palliative care (confusing it with hospice), time constraints, or financial burdens. Further research is needed to determine the most effective model for early palliative care integration, including patient acceptance factors.

Conclusion

This project demonstrated the feasibility of integrating a palliative care screening tool into routine clinical practice. Using such a tool effectively increases awareness of palliative care needs and subsequently boosts referrals. Improving tool accessibility, such as EMR integration with automated alerts, could further enhance tool utilization. Moreover, increasing provider focus on palliative care and addressing patient acceptance are crucial for comprehensive palliative care screening and timely referrals. Implementing palliative care screening tools holds significant promise for facilitating early palliative care referrals, ultimately leading to improved symptom management and enhanced quality of life for glioblastoma patients.

Appendix A. Glioma Palliative Care Screening Tool

| Screening items | Points | Patient points |

|---|---|---|

| Progressive MRI at current visit | 2 | |

| Functional status of patient (ECOG score/KPS score) | 0–4 | |

| 0: ECOG 0 = KPS 90%–100% | ||

| 1: ECOG 1 = KPS 70%–80% | ||

| 2: ECOG 2 = KPS 50%–60% | ||

| 3: ECOG 3 = KPS 30%–40% | ||

| 4: ECOG 4 = KPS 10%–20% | ||

| Any serious complication of cancer associated with a prognosis of | 1 | |

| Presence of one or more serious comorbid disease associated with poor prognosis (e.g., moderate-to-severe CHF, stroke, cognitive deficit, renal disease, liver disease, PE, bowel perforation, cerebral edema, obstructive hydrocephalus, cytopenia or NEW active problem requiring intervention or admission) | 1 | |

| Presence of palliative care problem | 1 | |

| • Uncontrolled symptoms (e.g., GI symptoms, headaches, fatigue, rash) | 1 | |

| • Moderate-to-severe distress (NCCN Distress Thermometer score of 4 or higher) | 1 | |

| • Patient/family concerns regarding course of disease and decision making | 1 | |

| • Patient/family requests palliative care consult | 1 | |

| • Team needs assistance with decision making | ||

| Total | 0–13 | |

| Refer the patient to palliative care when the score ≥ 5 | ||

| If the screening tool is not used, please write the reason below __________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

Note. ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; KPS = Karnofsky Performance Status; CHF = congestive heart failure; PE = pulmonary embolism; GI = gastrointestinal; NCCN = National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Adapted from Glare et al. (2011).

Appendix B. Provider Questionnaire

| Day

| __________ |

|—|—|

| Age | __________ |

| Diagnosis | __________________________________ |

| Sex | M/F |

| NCCN Distress score | __________ |

| Are you an APP? | □ Yes □ No: Fellow/Resident/Med student |

| Screening score ≥ 5? |

| □ Yes □ No |

| Palliative care discussion with the patient done? |

| □ Yes □ No |

| Referral made? |

| □ Yes □ No |

| If yes, referral made to |

| □ Duke palliative care |

| □ Recommended to patient’s local oncologist for palliative care referral |

| If screening score ≥ 5, and discussion did NOT take place and/or referral NOT made, why? |

| □ Patient refused |

| □ Provider did not agree: Attending/APP (please circle one) |

| □ Other: ___________________________________________________________________________________________ |

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Adelson, K., Paris, J., Ezeji-Okoye, S. C., Grieco, A., Tran, B., Meier, D. E., & Smith, C. B. (2017). Integrating palliative care into primary care for patients with advanced cancer: A pilot study. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 20(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0253

- Albizu-Rivera, L., Duprey, A., Prez-Stable, E. J., Chao, C., Portenoy, R. K., & Covarrubias, C. (2016). Palliative care guideline adherence among national comprehensive cancer network member institutions. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 14(9), 1113–1121. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2016.0113

- Alcedo-Guardia, A., Labat, J. P., Blas-Boria, D., & Vivas-Mejia, P. E. (2016). Trends in survival of patients with glioblastoma multiforme in a community hospital from 2005 to 2014. Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal, 35(4), 206–211.

- Begum, N. (2013). Impact of palliative care screening on referral patterns in an outpatient oncology clinic. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 16(7), 762–765. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.0505

- Davis, M. P., Temel, J. S., Balboni, T., & Glare, P. (2015). Integration of early palliative care for patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(26), 2835–2842. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.61.1010

- El-Jawahri, A., Traeger, L., Greer, J. A., Van Der Heide, M., Eichmann, M., Pirl, W. F., … Temel, J. S. (2016). Effect of early palliative care vs usual care on quality of life, mood, and survival among patients with advanced cancer: A meta-analysis. JAMA Oncology, 2(9), 1155–1169. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0518

- Ferrell, B. R., Temin, S., Alesi, E. R., Balboni, T. A., Basch, E. M., Breitbart, W., … Person, H. (2017). Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 35(1), 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474

- Glare, P. A., & Chow, R. (2015). Validation of a palliative care screening tool in a medical oncology inpatient unit. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 18(12), 1036–1042. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0196

- Glare, P., Semple, D., Stabler, M., & Saltz, L. (2011). Integration of oncology and palliative care. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 61(6), 371–384. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20112

- Grudzen, C. R., Richardson, L. D., Johnson, A., Hu, J., Hwang, U., Morrison, R. S., & Smith, C. B. (2016). The effect of early palliative care on emergency department use among patients with advanced cancer. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 67(6), 683–691.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.11.017

- Hui, D., Kim, Y. J., Park, S., Zhang, Y., Strasser, F., Cherny, N. I., & Bruera, E. (2015). Integration of early palliative care into standard oncology care: A systematic review. The Oncologist, 20(2), 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0427

- Kumar, P., Woo, J. L., Tan, S. Y., Tan, Y. H., Low, C. Y., Tambyah, P. A., & Krishna, L. K. (2012). Barriers to the integration of palliative care in oncology in a tertiary hospital: Perspectives of oncologists and palliative care physicians. Palliative & Supportive Care, 10(3), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1017/psc.2011.14

- Nakajima, N., & Abe, K. (2016). Effectiveness of early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliative Medicine, 30(3), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315605576

- Ostrom, Q. T., Gittleman, H., Liao, P., Vecchione-Koval, T., Wolinsky, Y., Brenes, M., … Barnholtz-Sloan, J. S. (2017). CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2009-2013. Neuro-Oncology, 19(suppl_5), v1–v88. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox158

- Perrin, K. O., & Kazanowski, M. (2015). Palliative care: What every resident should know. Family Medicine, 47(1), 25–32.

- Salins, N., Ramanjulu, R., Patra, A., Deodhar, J., & Muckaden, M. A. (2016). Effect of early integrated palliative care in patients with advanced cancer receiving chemotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 22(4), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1075.191735

- Swarm, R. A., & Dans, M. (2018). NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Palliative care. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 16(5), 563–573. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2018.0047

- Temel, J. S., Greer, J. A., El-Jawahri, A., Fishbein, K. A., Baile, W. F., Jackson, V. A., … Pirl, W. F. (2016). Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 34(8), 836–844. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.63.8307

- Vanbutsele, G., Pardon, K., Van den Eynden, B., Deliens, L., De Laat, M., Bilsen, J., & Deschepper, R. (2018). The effects of early palliative care on patients with incurable cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26(2), 345–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3928-y

- Walbert, T. (2014). Palliative care, hospice care, and end-of-life care in neuro-oncology practice. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 14(12), 501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-014-0501-6

- Walbert, T., & Khan, M. (2014). Palliative care for adults with malignant gliomas. Seminars in Oncology, 41(3), 374–384. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.04.008