Abstract

Objectives

Determining optimal nurse staffing levels in hospital wards remains a complex challenge. This study investigates the accuracy of the Safer Nursing Care Tool (SNCT) patient classification system in estimating nurse staffing needs across varying sample sizes. It further examines the alignment between SNCT-recommended staffing levels and healthcare professionals’ assessments of adequate staffing.

Design

This observational study integrates datasets of staffing requirements, as calculated by the SNCT, with nurses’ professional evaluations of staffing adequacy. Multilevel logistic regression modeling was employed for analysis.

Setting

The research was conducted across 81 medical and surgical units within four acute care hospitals.

Participants

Data encompassed 22,364 unit days, linking staffing levels and SNCT ratings with nurse-reported perceptions of having “enough staff for quality care.”

Primary Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes were staffing requirements estimated by the SNCT and nurses’ subjective assessments of staffing adequacy.

Results

Utilizing the recommended minimum sample of 20 days, the SNCT estimated the required staffing establishment with a mean precision of 4.1%. However, achieving estimations within ±1 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff member for most units necessitated significantly larger sample sizes. When actual staffing fell below SNCT recommendations, each hour per patient day of registered nurse staffing deficit was associated with an 11% decrease in the odds of nurses reporting sufficient staff for quality care. Conversely, the odds of nurses reporting missed necessary care increased by 14%. No definitive threshold indicating an ideal staffing level emerged. Surgical specialization, patient turnover, and a higher proportion of single rooms were correlated with lower odds of perceived staffing adequacy.

Conclusions

The SNCT offers reliable estimates for nurse staffing establishments, although sample sizes exceeding the recommended minimum are generally needed for precise results. While SNCT measurements of nursing workload correlate with professional judgements, the tool’s recommended staffing levels may not consistently be perceived as optimal. Certain systematic factors influencing staffing requirements in specific units remain unaccounted for. The SNCT serves as a potentially valuable tool to support professional judgement but should not replace it.

Trial Registration Number

Keywords: quality in health care, human resource management, health services administration & management

Strengths and Limitations of This Study

- This large-scale study, conducted over a year across 81 units in four hospitals, surpasses most nurse staffing tool evaluations in scope.

- It provides the first independent evaluation of the SNCT, a tool widely implemented in hospitals throughout England.

- The observational design measured associations between staffing deficiencies, as measured by the SNCT, and subjective professional assessments of staffing adequacy.

- The study did not assess the impact of staffing levels on objective patient care outcomes.

Introduction

In acute care hospitals, accurately determining and deploying the ‘right’ number of nursing staff per shift is critical for both operational efficiency and quality of patient care. Nursing staff constitute the largest workforce group and a significant variable cost for hospitals, often making nursing budgets a target for cost-saving initiatives.1 Conversely, insufficient nurse staffing is demonstrably linked to compromised care quality and patient safety.2 Despite the availability of numerous staffing tools and extensive research, robust evidence supporting the reliability and accuracy of these tools in estimating staffing requirements remains limited.3 4 This paper focuses on the Safer Nursing Care Tool (SNCT), prevalent in the majority of acute hospitals within the UK’s National Health Service (NHS)5 and endorsed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),6 the NHS’s evidence-based guideline body. We explore the reliability and precision of SNCT-derived estimates for required staffing establishments—the number of nurses needed for a hospital unit—and the extent to which these estimates align with professional judgements of sufficient staffing. Despite its widespread adoption and the critical nature of these considerations, these aspects of the SNCT have not been previously rigorously investigated.

Numerous studies have established correlations between higher registered nurse staffing levels in hospitals and improved patient care quality.2 7–9 These positive outcomes include reduced in-hospital mortality risks,10 shorter hospital stays,11 and fewer instances of necessary care omissions.12 Such findings have driven policies mandating minimum nurse staffing levels in various regions, including California in the USA, certain Australian states, and, more recently, Germany.13 However, studies linking staffing levels to outcomes often lack clear guidance on optimal staffing numbers for diverse patient needs, despite evidence of significant variability in these needs. Few studies have explored potential tipping points in these relationships that might indicate ideal staffing levels.2 14 15

Consequently, tools and systems designed to guide decisions about nurse staffing numbers—both for overall employment and daily shift deployment—remain widely used, either alongside or as alternatives to mandatory minimum staffing ratios. At the core of most such tools is a patient-level assessment method, which translates patient needs into required nursing time.3 4 While numerous tools exist, many lack strong empirical validation. Studies supporting these tools often merely demonstrate a correlation between tool-estimated staff demand and other demand measures. In the absence of a definitive ‘gold standard’ and without confirming whether tool-recommended staffing levels are indeed sufficient for delivering necessary care, such evidence remains limited. Different tools, while potentially showing correlated results, can yield dramatically different staffing estimates for the same patient group.4 For example, implementing a new system to estimate staffing needs for low-acuity wards resulted in an estimate double that of the existing system.16

Moreover, although a primary rationale for using staffing tools is the assertion that variable patient needs cannot be effectively met by fixed staffing levels,17 the impact of this variability on the precision of average staffing requirement estimates has received scant attention. While inter-rater reliability and agreement are frequently reported, the precision with which unit staffing requirements are estimated—whether daily or over time—is not adequately addressed.4

The SNCT18 is reportedly used in 80% of NHS acute hospitals in England.5 Initially designed to determine the required number of staff to employ per unit—the staffing establishment—to ensure adequate daily rosters for average patient needs, it is increasingly used to monitor and manage daily staffing demands. However, it is not used for billing purposes in England, where billing is activity-based and does not explicitly account for nursing staff. The SNCT is a patient classification system.4 At least daily, patients are categorized into one of five groups based on acuity and dependency, each group assigned a weighting (a ‘multiplier’) reflecting required nursing staff time.18 At the time of this study, the most recent multipliers for general adult inpatient units were based on 40,000 patient care episodes.6 These multipliers represent average staff time for direct patient care and ancillary tasks for each patient group, adjusted for annual leave, study time, and sick leave when determining staffing establishments.18

The SNCT exhibits strong correlation with alternative classification systems and high inter-rater agreement.19 20 However, despite the tool’s handbook recommending a minimum 20-day sample for reliable baseline establishment setting, evidence of the resulting estimates’ precision is lacking. Our literature review found no direct evidence that using the SNCT or any similar tool improves care quality.4 Consequently, we adopted professional judgement as the ‘gold standard’ in this study, as no tool has been shown to offer a more accurate measure of required staffing.

This observational study aims to evaluate the reliability and validity of the SNCT by assessing the precision of its establishment estimations and the association between staffing shortfalls (relative to SNCT recommendations) and nurses’ judgements of staffing sufficiency for delivering quality care. Recognizing that factors like patient turnover, specialty, and unit layout—not directly considered in patient classifications—may influence staffing needs,21–23 we also investigate whether SNCT-determined staffing levels adequately accommodate demand variations linked to these factors. Specifically, we examine the independent association between these factors and staffing adequacy judgements, considering the impact of deviations from SNCT-recommended staffing.

Methods and Materials

This research draws on data and methods detailed in a previous publication in the NIHR Journals Library Health Services and Delivery Journal.24 We utilized routinely collected data and nurse reports from 81 acute medical/surgical units (2178 beds) across four NHS hospital trusts (referred to as ‘hospitals’) in England over one year (2017). Daily data for each unit included: deployed staffing levels (from electronic rosters), required staffing levels (based on SNCT patient classifications), and nurses’ professional judgements of care completeness and staffing adequacy for quality care (via a microsurvey integrated into daily assessments). SNCT assessments and staffing adequacy evaluations were provided by the nurse in charge of each shift, referred to as the ‘shift leader.’

Setting and Inclusion

The study sites comprised a university teaching hospital, two general hospitals, and a specialist cancer hospital (two sites) located in London, South East, and South West England. These hospitals serve diverse populations, including rural areas, inner-city communities, and national specialist referrals. All hospitals conducted nurse staffing establishment reviews at least biannually. Two had long-standing SNCT usage, while the other two adopted it shortly before the study began.

We included general medical and surgical units providing 24-hour inpatient care. Units outside the SNCT scope (e.g., paediatrics, intensive care, maternity, neonatal, palliative care) and those with atypical staffing requirements (e.g., bone marrow transplant, isolation units), as identified by a local co-investigator, were excluded. Our unit sample represented 74% of all beds across the four hospitals.

Data Sources and Measures

Shift leaders recorded patient counts in each SNCT category and assessed staffing adequacy (described below) in electronic systems at least twice daily over one year. Local leads trained shift leaders on participating units in SNCT use and staffing adequacy question completion. Laminated sheets with supporting information and brief guidance were available near unit computers used for data entry. Additional data (rosters, patient admissions/discharges) were routinely collected for administrative purposes. Each hospital provided unit profiles detailing specialty and layout, including bed numbers and single rooms.

Study Variables

We used the most current SNCT multipliers available at study initiation.18 We used reported patient counts per category to calculate a daily weighted average multiplier per unit, multiplied by the patient count from the patient administration system (to account for potential omissions in shift leader reports). This yielded an estimated unit staffing establishment (number of staff to employ). We primarily used morning assessments (substituting later assessments if morning data were missing) and 07:00 patient counts. The SNCT calculation provides the staffing establishment, inclusive of uplifts for staff leave and sickness. We converted this to implied daily staff hours, using a 37.5-hour work week per FTE and removing the 22% ‘uplift’ for leave, study, and sick leave, assuming this uplift sufficiently covered long-term absences.

For each unit, we used the average observed skill mix as a proxy for the planned mix of registered nurses and nursing assistants. The SNCT does not directly account for patients needing one-to-one supervision (‘specialing’)25, despite its high implied staffing demand. Thus, for daily staffing requirement estimations, we added hours for ‘specialing’ patients based on records. However, when estimating establishments, we made no additional allowance, as such enhanced care would be part of the observed care informing SNCT multipliers.

From electronic rosters, we identified daily hours worked by registered nurses and nursing assistants (07:00 to 07:00), dividing these by patient days (patient hours/24) to calculate hours per patient day (HPPD) for each unit. Staffing shortfall was calculated by subtracting required hours (SNCT plus specialing) from actual daily deployed hours. Negative shortfalls indicated staffing exceeding requirements. Daily patient turnover per staff member was also calculated (patient admissions and discharges divided by total staff hours).

Outcomes measured included nurse-reported staffing adequacy variables, assessed by shift leaders. They responded to three brief items alongside SNCT ratings, directly inputting responses into the SNCT system (see box 1). We selected three items pragmatically, judging that more would be overly burdensome and potentially reduce data quality. Two items, adapted from the RN4CAST/International Hospital Outcomes surveys,12 26 assessed whether staffing was sufficient for quality care and whether necessary care was left undone. We also inquired about missed staff breaks, as nurses might forgo breaks to complete care, mitigating adverse effects of staffing shortages.27 These questions constituted the microsurvey.

Box 1. Staffing Adequacy Questions

Questions

- Were there enough nursing staff to provide quality care on the last shift?

- Was necessary nursing care left undone (missed) on the last shift because there were too few nursing staff?

- Were staff breaks missed on the last shift because there were too few nursing staff?

Data Cleaning and Analysis

Data cleaning, processing, and statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software V.3.5.0.28 We identified and removed extreme staffing shortfall values exceeding the mean ±3 SD (approximately 1.5% of cases), which removed atypical periods (e.g., Christmas) or extreme errors in SNCT ratings. For major changes like unit moves, patient population shifts, or bed number alterations, unit data were split and treated as separate units. We detected consistent reverse coding (0/1 for yes/no) for staffing adequacy questions in several units of one hospital, likely due to erroneous staff training. Discovered mid-study, we developed logical rules to identify affected units and recode data, assessing implications via sensitivity analyses excluding this hospital.

To evaluate establishment estimate accuracy, we considered the SNCT’s minimum recommended 20-day sample for data collection (twice yearly). We used 1000 bootstrap samples of 20 days’ data to estimate mean establishment with a 95% CI per unit. This was repeated with increasing sample sizes to assess accuracy gains. For each unit, we calculated estimate precision (CI half-width as % of mean) and CI absolute value in FTE staff. We determined units with CI widths ≤2 FTE (±1 FTE from mean) or ≤1 FTE (±0.5 FTE).

We modeled the relationship between staffing deficits (HPPD) and nurse-reported staffing adequacy measures using multilevel logistic regression. We used the first daily SNCT rating (morning or later if missing), 7 am patient count, actual staffing and patient hours (7 am-7 am), and staffing adequacy recorded the following morning. Models were fitted using the glmer function from the lme4 package29 in R, with staffing nested within unit, and units nested within hospitals. All models controlled for day of week, single room proportion, turnover, and unit specialty (surgical vs. medical/mixed). We assessed associations of staffing adequacy outcomes with deviations in both registered nurse and nursing assistant staffing from estimated requirements. We also modeled deviations in total hours and skill mix (registered nurse proportion).

After modeling linear and main effects, we added quadratic terms for staffing level variables to test for non-linear relationships and explored variable interactions. Model fit was compared using Akaike information criteria (AIC) and Bayesian information criteria (BIC), favoring lower values indicating better fit/parsimony.30

Patient and Public Involvement

During research proposal development, we consulted with patient/public involvement experts. Based on their guidance, we did not seek direct patient/public involvement in question prioritization, as these questions were driven by the need for technical SNCT assessment. Instead, we focused on public involvement in research governance and dissemination. We included a lay member with relevant expertise on our steering group and considered ward-based staff nurses as end-users, analogous to patients receiving expert-recommended treatments. We engaged with ward staff via social media and consultation events.

Ethical Approval and Registration

The study was prospectively registered.31 NHS Research Ethics Committee approval was not required, as no direct patient data were collected, and all patient data were pseudoanonymized at source.

Results

Usable SNCT ratings were obtained for 96% of occasions, and staffing adequacy question responses for ≥85% of occasions. After data cleaning and linkage, we analyzed 22,271, 22,294, and 22,364 unit days for associations between staffing shortfalls and reports of missed breaks, undone care, and adequate staffing, respectively.

Average unit staffing levels and skill mix varied significantly across and within hospitals (table 1). Hospital-level average estimated staffing requirements closely matched observed staffing in 3 of 4 hospitals, though all were somewhat understaffed (≤8%). Larger discrepancies between actual staffing and SNCT estimates occurred in smaller, often specialist, units with more single rooms (apparent overstaffing) and some larger medical units (extreme understaffing). In hospital C, a specialist hospital with many small units, average unit staffing exceeded SNCT estimates by 50%.

Table 1. Mean and Range of Units’ Average Daily Staffing Levels, Skill Mix, and SNCT Estimated Staffing Requirements

| Hospital | Total hours per patient day | Skill mix (% registered nurses) | Estimated staffing requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Min | Max | |

| A | 7 | 5.4 | 10.4 |

| B | 6.8 | 5.0 | 8.9 |

| C | 10.5 | 7.5 | 14.2 |

| D | 6.5 | 5.2 | 8.4 |

| All | 7.3 | 5.0 | 8.4 |

SNCT, Safer Nursing Care Tool.

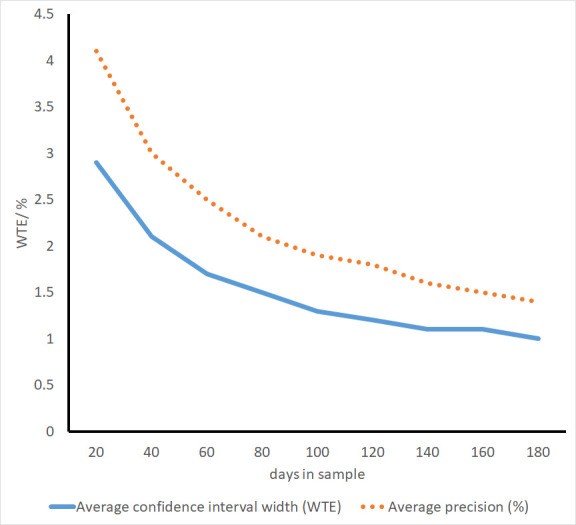

Across all units, using the recommended minimum 20-day data, average precision was 4.1% (range 0.6%–13.5%). In absolute terms, the average 95% CI width for establishment was 2.9 FTE staff (approximately mean ±1.5 FTE). CI width was ≤2 FTE in 27/86 units and ≤1 FTE in only 3/86.

Precision markedly increased with larger sample sizes (figure 1). With 40 days, most units (56/86) achieved CI width ≤2 FTE. Benefits of increased sample sizes diminished beyond this, and even with 180 days, only 53/77 units had CI width ≤1 FTE (table 2).

Figure 1.

Mean precision and CI width of staffing establishment estimates with different sample sizes. WTE, whole time equivalent.

Table 2. Average Widths of 95% CIs for the Mean Using Different Sample Sizes to Estimate Establishment

| Sample size taken for the estimate | Average CI width (WTE) | Average precision (%) | Number units with CI width 1 WTE or less | Number units with CI width 2 WTE or less | Number of units* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 3 | 27 | 86 |

| 40 | 2.1 | 3.0 | 7 | 56 | 86 |

| 60 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 10 | 64 | 86 |

| 80 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 20 | 72 | 86 |

| 100 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 31 | 74 | 82 |

| 120 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 39 | 74 | 81 |

| 140 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 44 | 74 | 81 |

| 160 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 50 | 75 | 80 |

| 180 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 53 | 73 | 77 |

*Because units with establishment and/or specialty changes were treated as separate units for analysis, the total exceeds the number of units participating in the study. As the available data for some units was less than the sample required for the estimate, the number of units for larger samples is reduced.

WTE, whole time equivalent.

Across units, shift leaders assessed a mean of 78% of shifts as having enough staff for quality care (unit range 24%–100%). Necessary care was reported left undone due to insufficient staff on 5% of shifts (range 0%–25%), and breaks were missed on 5% of shifts (range 0%–29%).

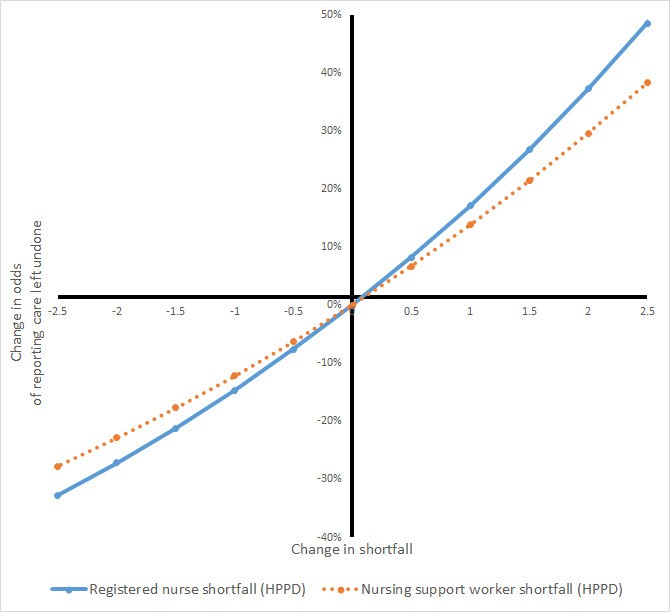

Staffing shortfalls relative to SNCT-estimated daily requirements were associated with nurses’ perceptions of staffing adequacy (table 3). In multivariable models, each registered nurse hour shortfall reduced the adjusted odds of shift leaders reporting adequate staffing for quality by 11%, increased odds of reporting undone care by 14%, and increased odds of missed breaks by 12%. Similar findings were observed for nursing assistant shortfalls.

Table 3. Association Between Staffing Shortfall and Nurse Perceptions of Staffing Adequacy: Univariable and Multivariable Models

| Variable | Enough staff for quality | Nursing care left undone | Staff breaks missed |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR* | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | |

| Registered nurse shortfall (HPPD) | 0.94 | 0.89 | (0.87 to 0.92) |

| Nursing assistant shortfall (HPPD) | 0.90 | 0.86 | (0.83 to 0.89) |

| Turnover (per nursing hour) | 0.35 | 0.91 | (0.30 to 2.75) |

| Unit type | |||

| Medical or mixed (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Surgical | 0.57 | 0.54 | (0.31 to 0.92) |

| Proportion single rooms | 0.89 | 0.54 | (0.18 to 1.66) |

| Day of week | |||

| Monday (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Tuesday | 1.11 | 1.12 | (0.99 to 1.26) |

| Wednesday | 1.28 | 1.28 | (1.13 to 1.45) |

| Thursday | 1.09 | 1.08 | (0.96 to 1.23) |

| Friday | 1.03 | 1.03 | (0.91 to 1.17) |

| Saturday | 1.28 | 1.29 | (1.14 to 1.47) |

| Sunday | 1.02 | 1.02 | (0.90 to 1.15) |

| Variance partition coefficient for units** | 0.22 | ||

| Variance partition coefficient for hospitals** | 0.12 | ||

| Akaike information criterion | 20 697 | ||

| Bayesian information criterion | 20 809 |

Ref: reference category for categorical variables.

*OR derived from entering this variable only into the multilevel model. **Calculated as between-group residual variance divided by total variance using the latent variable approach.46

HPPD, hours per patient day.

Factors beyond SNCT-estimated shortfalls also influenced staffing adequacy perceptions. Nurses in surgical units were less likely to perceive adequate staffing than those in medical/mixed units, with lower odds of reporting sufficient staff and higher odds of reporting undone care or missed breaks. For instance, the odds of reporting adequate staffing were 46% lower in surgical units. Although not statistically significant with wide CIs, units with higher single-room proportions showed substantially lower odds of reported staffing adequacy. Similarly, higher single-room proportions and turnover were associated with increased odds of reporting undone care and missed breaks, though CIs were wide and relationships not statistically significant. Nurses were more likely to report adequate staffing and less likely to report missed care and breaks on Saturdays versus Mondays, but no consistent weekend-weekday difference pattern emerged.

Non-linear relationship testing with registered nurse and nursing assistant shortfalls, expected if SNCT indicated a staffing adequacy threshold, revealed a significant non-linear term for registered nurse staffing concerning undone care. However, model preference was unclear (AIC: Δ−2, BIC: Δ+14 vs. main effects model), and the overall relationship remained largely unchanged. No threshold indicating benefit/harm onset was observed (figure 2). For other outcomes, non-linear terms were non-significant and increased AIC and BIC (online supplementary table 1).

Figure 2.

Change in odds of reporting care left undone with change in staffing shortfalls estimated from model with non-linear staffing effects. HPPD, hours per patient day.

Supplementary data

bmjopen-2019-035828supp001.pdf (155.3KB, pdf)

Models including statistically significant variables and interactions between staffing shortfall and these variables showed no significant interaction effects between registered nurse and nursing assistant shortfalls, and AIC and BIC increased, favoring simpler models (online supplementary table 2).

Models using total care hour shortfall (registered nurses and assistants) per patient day yielded similar coefficients, with each care hour shortfall associated with a 12% reduction in adequate staffing odds, and no significant skill mix associations (online supplementary table 3). Sensitivity analyses excluding data from the hospital with coding errors showed largely unchanged results and no impact on substantive conclusions (see online supplementary table 4 for example).

Discussion

This study presents the first independent evaluation of the SNCT, a widely adopted tool for determining staffing levels in English hospitals. Using the recommended 20-day minimum sample, estimates of required nurse numbers per ward showed an average precision of 4.1%, but with wide CIs for absolute staff numbers. A 40-day sample yielded estimates within ±1 staff member for most wards, but much larger samples (≥140 days) were needed for CI widths ≤1 staff member in most wards. High staffing shortfalls, relative to SNCT-estimated daily requirements, correlated with reduced nurse reports of adequate staffing for quality, and increased reports of missed care and staff breaks. These relationships appeared linear, lacking a threshold at SNCT-recommended levels. Factors beyond patient classifications, such as unit specialty and day of week, also influenced nurses’ perceptions of staffing adequacy.

The SNCT’s original purpose was to ensure sufficient nurse employment to meet patient care hour needs. While existing reports affirm the tool’s inter-rater reliability,19 20 the 20-day data recommendation acknowledges daily demand variability and potential imprecision in small sample estimates. The 4.1% average precision from 20 days appears superficially acceptable but masks considerable precision variation across units and large absolute staff number differences. Conventionally interpreting CIs (though technically slightly inaccurate), estimates for many units could deviate from true staffing needs by over two staff members, a potentially significant inaccuracy.

Modest increases in establishment estimation days substantially improve precision, with diminishing returns beyond 40 days. With increasing daily SNCT data collection in hospitals, this data could be leveraged for establishment reviews, reallocating resources from periodic reviews to unit report quality control. Moving averages could replace intermittent reviews, with statistical process control methods to detect establishment-revision-triggering demand changes.32

For some units, inherent variation may render precise establishment estimation perpetually challenging. Our findings also highlight substantial, unmeasured influences on demand from factors like unit layout and specialty. In these cases, professional judgement, already emphasized in SNCT guidance, is paramount. The apparent objectivity of measured quantities can easily overshadow substantial associated uncertainties.33 Both our results and broader literature underscore the essential role of professional judgement in nurse staffing decisions.3 4

While our findings on workload-influencing factors were imprecise, turnover and single rooms have been previously identified as increasing nursing workload,21–23 34 35 due to admission/discharge work, indirect care increases, and single-room patient surveillance needs. The SNCT acknowledges turnover-related workload, offering revised multipliers for acute admissions units.18 Our findings suggest within- and between-unit turnover variation is not fully accommodated by average patient demand. The lower perceived staffing adequacy in surgical units versus medical/mixed units may indicate higher surgical unit workload for given acuity/dependency levels, potentially from surgery-associated indirect care (e.g., transports, escorts).36 This novel finding is notable, as staffing recommendations or mandates typically do not differentiate medical and surgical units.37

While tool parsimony and accuracy must be balanced, these findings suggest SNCT recommendations fit some units better than others. Tailoring the tool to specific contexts could improve fit. Further SNCT revisions, such as unit-specific multipliers beyond current admissions unit multipliers, warrant further investigation. While wide CIs for single rooms and turnover do not directly support formal multiplier revisions, the importance of professional judgement regarding other workload factors is clear.

Although SNCT multipliers were initially derived from expert time estimates, subsequent revisions used empirical observations.20 Our study is the first to demonstrate that staffing shortfalls, relative to tool-estimated requirements, correlate with professional judgements of insufficient staffing for quality care, and other indicators of potential inadequacy. However, if SNCT levels were generally deemed sufficient for quality care, the shortfall-adequacy relationship should diminish above recommended levels. Instead, we observed linear relationships without a threshold. A similar finding emerged in a recent study using the RAFAELA system, prevalent in Northern Europe, where staffing above ‘optimal’ levels was associated with mortality reductions.38 39 Another recent study linked staffing below SNCT-determined establishments to increased in-hospital mortality risk,11 23 with a linear relationship for registered nurse staffing, lacking a threshold. Thus, while our findings support the SNCT as a workload measure, they do not validate its recommended levels as ‘optimal.’

Similar but independent effects of registered nurse and nurse assistant shortfalls on adequacy perceptions might suggest substitutability, but these roles are not interchangeable. Extensive research highlights registered nurse skill mix importance for patient safety.40 Recent studies also emphasize both registered nurses’ and assistants’ contributions to patient safety and interpersonal care quality.11 41 42 Simple substitutions are not feasible, as their contributions are distinct. Effective assistant deployment relies on sufficient RN supervision and support.11 41

While widely used in England, the SNCT is not the only available staffing tool. Despite numerous tools and reports, definitive data comparing SNCT precision to other establishment-estimating tools is scarce. Our reviews found no recent studies providing comparable data on other tools.3 4

Limitations

While unit nurses received SNCT training, the study’s scale likely means our ratings are less reliable than expert rater assessments in dedicated establishment reviews. However, the wide establishment estimate precision variation is unlikely solely due to this. Furthermore, our study conditions mirror routine SNCT use with daily shift leader assessments. We did find systematic coding errors for staffing adequacy assessments in some units, though substantive conclusions remained unaffected. However, this may indicate less systematic errors also occurred, potentially attenuating our ability to estimate relationships and thus underestimating the shortfall-adequacy relationship. We investigated correlations, and causality cannot be assumed. Our study did not explore staffing-objective care outcome relationships, relying on subjective nurse reports of adequacy, which are, however, associated with important patient outcomes.43–45 We did not assess overstaffing consequences. Judgements of staffing adequacy and SNCT ratings were made by the same individuals, potentially introducing bias, though the distinct nature of SNCT reports (patient category counts) and adequacy questions makes simple common method bias unlikely. Our large sample was from only four hospitals, limiting generalizability.

Conclusions

This study addressed several questions about the SNCT, questions pertinent to other staffing tools as well: establishment estimate precision, accommodation of non-patient-specific variation, and ‘optimality’ of recommended staffing levels. Our reviews indicate such questions are rarely posed or answered for other tools.

The SNCT can provide reliable unit staffing establishment estimates, but larger samples than currently recommended are needed for estimates within one FTE staff member of the mean in most units. For some units, such precision is difficult to achieve, and systematic variations in staffing needs associated with unit types may exist, unaccounted for by the SNCT. While we recommend further exploring SNCT reliability and validity and suggest moving averages over periodic reassessments for detecting establishment change needs, our findings reinforce that measurement is an adjunct to, not a replacement for, professional judgement. The SNCT appears to measure nursing workload, but its recommended staffing levels are not necessarily optimal.

Supplementary Material

Reviewer comments

bmjopen-2019-035828.reviewer_comments.pdf (550KB, pdf)

Author’s manuscript

bmjopen-2019-035828.draft_revisions.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rosemary Chable, Andrew Dimech, Jeremy Jones, Yvonne Jeffrey, Antonello Maruotti, Alejandra Recio Saucedo, and Nicola Sinden for funding and design contributions, and Clare Aspden, Tracey Cassar, and Shirley Hunter for data collection. We also acknowledge all nurses who completed staffing adequacy questions and SNCT ratings.

Footnotes

Twitter: @workforcesoton, @JaneEBall, @tommonks1

Contributors: PG (professor, health services research): principal investigator, conceptualization, study design, funding, data oversight, data analysis, interpretation, and drafting. CS (research fellow, operational research): descriptive and regression analyses, critical article revision. JB (professor, health services research): study design, funding, interpretation, critical revision. DC (senior medical statistician): statistical advice, interpretation, critical revision. NP (clinical professor, nursing): study design, funding, data acquisition, interpretation, critical revision. TM (principal research fellow, operational research and data science): study design, funding, data oversight, data analysis, interpretation, critical revision.

Funding: Funded by the UK’s National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research Programme number 14/194/21. JB, NP, PG, and TM were award holders.

Disclaimer: Funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, publication decisions, or manuscript preparation. Views are authors’ and not necessarily NHS, NIHR, NETSCC, PHR programme, or Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: PG is on the National Health Service Improvement safe staffing faculty steering group, ensuring consistent SNCT knowledge and application across the NHS.

Patient and public involvement: Patients/public involved in design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination. See Methods.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Approved by Health Research Authority (IRAS 190548) and University of Southampton Ethics committee (reference 18809).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data publicly available from University of Southampton repository: https://doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/D1134.

References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

bmjopen-2019-035828supp001.pdf (155.3KB, pdf)

Reviewer comments

bmjopen-2019-035828.reviewer_comments.pdf (550KB, pdf)

Author’s manuscript

bmjopen-2019-035828.draft_revisions.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)