1. INTRODUCTION

Despite advancements in cancer treatments, the global incidence of cancer deaths remains significant, underscoring the critical need for improved supportive and palliative care (PC). As cancer management evolves to extend patient survival, the demand for comprehensive palliative care, integrated early in the disease trajectory alongside active treatments, grows substantially. International medical societies advocate for this early integration, supported by evidence demonstrating that early PC intervention improves symptom management, including depressive symptoms, and enhances overall quality of life for cancer patients. Studies have shown that concurrent medical oncology and PC team interventions can lead to prolonged survival and better referral processes for patients nearing end-of-life care.

Integrating PC within comprehensive cancer centers is particularly crucial. However, the capacity of current PC teams often struggles to meet the increasing needs. To optimize patient care, oncology teams require effective methods to identify patients who would most benefit from timely PC. While prognostic scores exist, like the Palliative Prognostic Score (PaP), these are often better suited for predicting short-term mortality in hospice settings rather than proactively identifying PC needs. The complexity of individual patient situations and the limitations of solely prognosis-based criteria have led to a need for more need-based approaches in determining PC intervention.

Recent consensus suggests moving away from rigid instruments towards a combination of major and minor criteria for outpatient PC referrals, mirroring earlier approaches for inpatients. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has proposed a two-step screening process, with simplified versions also under evaluation. In France, the French Society for Palliative Support and Care (SFAP) introduced the PALLIA-10 questionnaire in 2010. This 10-item tool, designed for use by any caregiver, aims to provide a simple score (0-10) reflecting a patient’s palliative care needs. The PALLIA-10 offers an alternative approach to assess PC requirements, but its effectiveness, its correlation with actual PC interventions, and its impact on survival have remained largely unexplored. Current recommendations suggest referring patients with a PALLIA-10 score exceeding 3 to specialized PC teams. However, in comprehensive cancer centers, which often treat patients with advanced, heavily pre-treated disease, a more refined selection process may be necessary to effectively trigger PC team involvement. This prospective multicenter study was designed to evaluate the application of the PALLIA-10 questionnaire in hospitalized advanced cancer patients within comprehensive cancer centers, specifically investigating the appropriateness of the score threshold of 3 for initiating palliative care referrals.

2. METHODS

2.1. Patient Enrollment and Study Design

This prospective study was conducted across 18 French comprehensive cancer centers, enrolling adult inpatients from conventional medicine and radiotherapy departments. Patients in surgical units and outpatients were excluded from the study. All participants, and their family caregivers where applicable, were provided with detailed information about the study, both verbally and in writing, and were given the option to decline participation. The study received ethical approvals from the French advisory committee on information in health research (CCTIRS) and the national commission for informatics and rights (CNIL), was registered with the Ethic committee of Lyon Sud-Est IV, and is listed on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02479061).

Data collected included demographics (age, gender, family status), Karnofsky performance status (ECOG-PS equivalent), disease characteristics (diagnosis, setting), and overall medical management details, including the reason for hospitalization and PC requirements. The most recent biological data available within three weeks of enrollment were utilized.

The PALLIA-10 questionnaire was specifically intended for patients with incurable disease, as determined by current medical understanding. A national site initiation meeting was held to standardize procedures for enrollment, questionnaire administration, and data collection across all participating centers. Each center’s investigative team, comprising at least one physician and one nurse from the supportive care unit, received specific training on the use of the PALLIA-10 questionnaire and the SFAP-recommended scoring system (0-10). The SFAP guidelines emphasize that any healthcare professional should be able to complete the questionnaire, irrespective of their professional background. Patients or their caregivers were directly interviewed. Recruitment was conducted on a single designated day at each institution to ensure a uniform evaluation per bed. The stage of the disease (curative, early palliative, terminal palliative, or agonic) was classified according to the Krakowski classification system.

Survival data were updated six months post-study for all patients. For patients not already under PC management at the study’s outset, the date of PC initiation within the subsequent six months was also recorded, if applicable.

2.2. Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes assessed were the prevalence of palliative patients with a PALLIA-10 score greater than 3 within the hospitalized cancer center population, and the subsequent decisions regarding PC intervention. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients already receiving PC at study enrollment or referred to PC within six months, the prevalence of patients with scores exceeding 5, and overall survival (OS) based on the predefined score thresholds of 3 and 5.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The analysis focused on the palliative patient cohort. Palliative status was determined by a palliative entry date or, in its absence, by the medical oncologist’s assessment based on the Krakowski classification. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline patient characteristics. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of study inclusion to the date of death from any cause or censored at the last follow-up date. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests were used to analyze OS. The PALLIA-10 score thresholds of 3 and 5 were established prior to data analysis.

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to adjust the PALLIA-10 score (≤3, 4-5, and >5) for potential confounding variables. These variables included age at inclusion, reason for hospitalization, tumor type, PC management at inclusion, agreement among oncologist, healthcare team, and PC team opinions, Karnofsky score, number of metastatic sites, and biological parameters (hemoglobin, lymphocytes, LDH, albumin, and CRP). Variables with less than 10% missing values and significance at a 20% level were included in a backward selection process to identify factors significant at a 5% level in the final multivariate model. A multivariate Cox model was also conducted using the PALLIA-10 score as a continuous variable. Hazard Ratios (HRs) are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the correlation of pre-specified factors with PC management. This was done in two stages, first examining the PALLIA-10 score (≤3 and >3), and then further exploring PALLIA-10 scores (≤3, 4-5, and >5), family status, age at inclusion, hospitalization reason, tumor type, opinion convergence, Karnofsky score, metastatic site count, and biological parameters. Similar to the Cox model, variables with sufficient data and significance at a 20% level were subjected to backward selection to retain factors significant at a 5% level in the final model. Odd Ratios (ORs) are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis was conducted to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of PALLIA-10 scores. The Youden index J was used to determine the optimal cut-off point for sensitivity and specificity. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

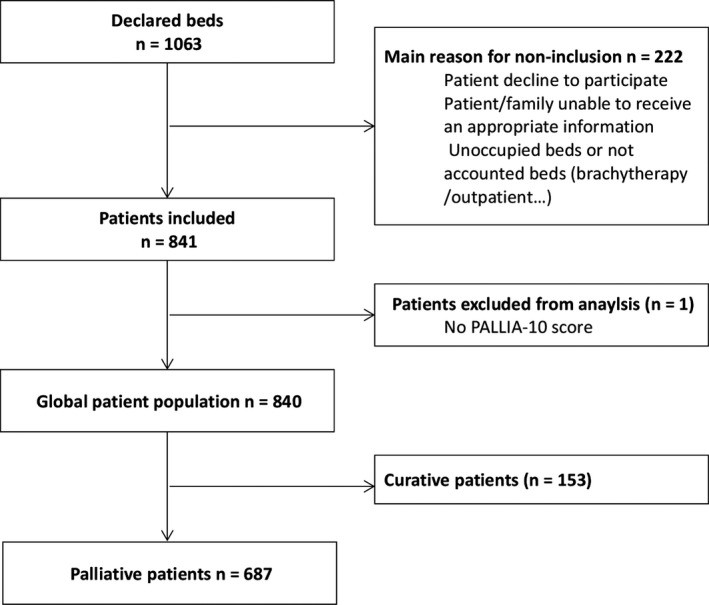

The study successfully enrolled 840 patients across 18 (90%) French Comprehensive Cancer Centers. Data collection was performed on a single day in each of sixteen centers between June 15th and 19th, 2015, with two additional sites participating on October 8th and 9th. These centers collectively reported 1063 hospital beds. After excluding minors, outpatients, brachytherapy units, and unoccupied beds, 687 (82%) patients were identified as being in a palliative care setting (Figure 1). The PALLIA-10 score was missing for only one patient.

Figure 1.

The median age of participants at inclusion was 64.8 years (range 19-92), with 371 (54.0%) being women and 490 (71.3%) living with a caregiver. A majority, 587 (85.4%), had a performance status (PS) of ≥ 2. The most frequent primary tumor locations were the digestive tract (18.3%), breast (17.6%), and lung/pleura (14.7%). Metastatic disease was present in 599 (87.4%) patients, with 69.3% having more than two metastatic sites. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main demographics and baseline characteristics of palliative care patients. Data presented as median (range min-max) or n (%).

| Patients in palliative setting N = 687 | |

|---|---|

| Median age at inclusion (years) | 64.8 (19‐92) |

| Median age at diagnosis (years) | 61.6 (12‐90) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 371 (54%) |

| Male | 316 (46%) |

| Familial status | |

| Missing data | 1 |

| Alone | 167 (24.3%) |

| Caregiver at homea | 490a (71.4%) |

| Dependent person at home | 29 (4.2%) |

| Performance Status (ECOG‐PS) | |

| 0 | 5 (0.7%) |

| 1 | 95 (13.8%) |

| 2 | 202 (29.4%) |

| 3 | 210 (30.6%) |

| 4 | 175 (25.5%) |

| Main primary tumor localizationsa | |

| Digestive tract | 126 (18.3%) |

| Breast | 121 (17.6%) |

| Lung and/or pleura | 101 (14.7%) |

| Head and Neck | 63 (9.2%) |

| Urologic | 82 (11.9%) |

| Gynaecologic | 78 (11.4%) |

| Metastatic disease | |

| Missing data | 2 |

| Metastatic disease | 599 (87.4%) |

| Median number of metastatic sites | 2.0 (0‐8) |

| Reason(s) for hospitalization | |

| Treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy…) or health assessments | 212 (30.9%) |

| Acute complication (aplasia, sepsis, Intracranial hypertension…) | 137 (20.0%) |

| Symptoms (pain, dyspnea…) | 338 (49.2%) |

| Median delay between hospitalization date and inclusion (days) | 6.0 (0‐77) |

| Patients with entry date in palliative setting | 668 (97.2%) |

| Median delay between initial diagnosis and palliative settinga (months) | 3.0 (0‐414) |

| Palliative care management initiated at the time of the inclusion | 216 (31.4%) |

| Median delay between initial diagnosis and palliative care initiation (months) | 20.7 (0‐374) |

| Reasons for palliative care request | |

| Symptoms | 161 (74.5%) |

| Psychological support | 87 (40.3%) |

| Orientation of the patient | 77 (35.6%) |

| Support for the patient’s family | 40 (18.5%) |

| Healthcare team support | 24 (11.1%) |

| Terminal accompaniment | 18 (8.3%) |

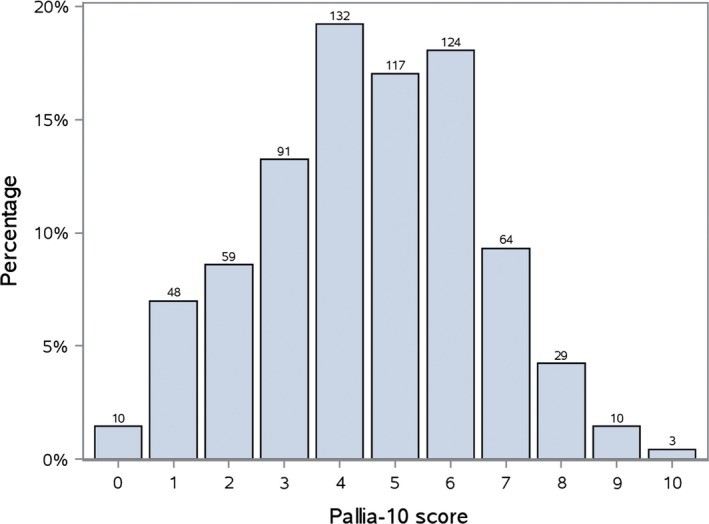

The distribution of PALLIA-10 scores is shown in Figure 2. Among palliative patients, 479 (69.7%, 95%CI 66.1%-73.1%) had a score greater than 3, and 230 (33.5%, 95%CI 30.0%-37.1%) had a score exceeding 5.

Figure 2.

3.1. Palliative Care Management

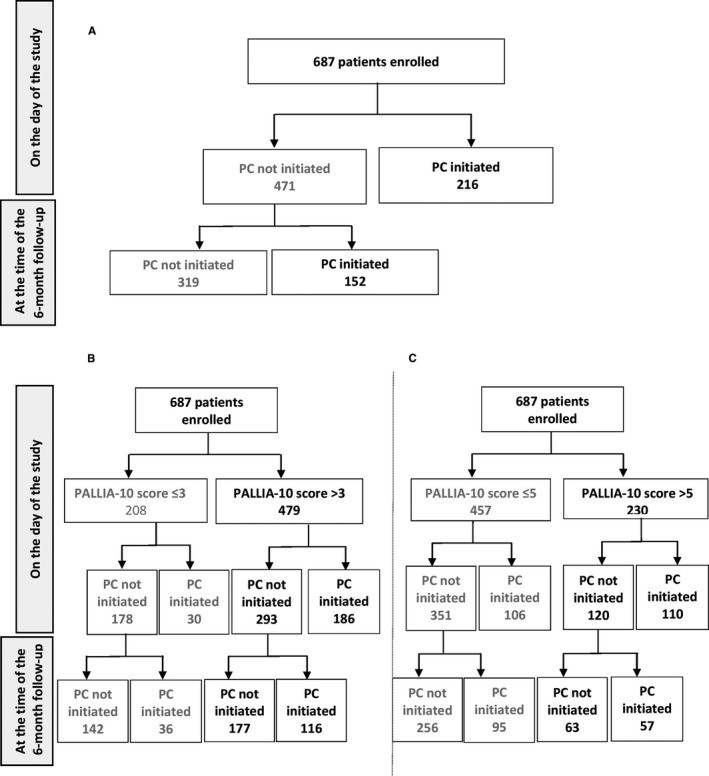

At the time of the study, 216 (31.4%) patients, with a median PALLIA-10 score of 6 (range 0-9), were already receiving palliative care. Of these, 186 had a PALLIA-10 score greater than 3 (38.8% of all patients with scores >3), and 110 had scores greater than 5 (47.8% of those with scores >5). The 471 (69%) patients not receiving PC at study entry had a median PALLIA-10 score of 4 (range 0-10). Within this group, 293 had scores >3 (61.2% of patients with scores >3), and 120 had scores >5 (52.2% of patients with scores >5) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

PC initiation began within six months following the study for 152 (22.1%) patients, who had a median PALLIA-10 score of 4.5 (range 0-10) at study enrollment. This included 116 patients with scores >3 (24.2% of patients with scores >3) and 57 patients with scores >5 (24.8% of patients with scores >5).

Logistic regression analysis revealed an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 2.6 (95%CI 1.65-4.11) for PC referral for patients with a PALLIA-10 score >3, indicating a significantly higher likelihood of referral with higher scores. Further analysis showed adjusted ORs of 1.9 (1.17-3.16) for scores 4-5 and 3.59 (2.18-5.91) for scores >5. The PALLIA-10 score remained significantly correlated with PC team intervention even after adjusting for metastatic sites, opinion convergence among healthcare teams, and reasons for hospitalization (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictive factors for palliative care team intervention: Multivariate model results.

| Variables | OR | 95%CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PALLIA 10 Score | [0‐3] (Ref.) | 1.00 | |

| [3‐5] | 1.924 | [1.169‐3.165] | |

| [5‐+] | 3.595 | [2.185‐5.914] | |

| Number of metastatic sites | No metastatic site (Ref.) | 1.00 | |

| One metastatic site | 0.426 | [0.214‐0.846] | |

| At least two metastatic sites | 0.663 | [0.356‐1.235] | |

| Opinion convergence (oncologist/health team/Palliative care team) | At least one disagree (Ref.) | 1.00 | |

| All agree | 3.942 | [1.939‐8.017] | |

| Reasons of hospitalisation | Treatment (Ref.) | 1.00 | |

| Complications | 2.731 | [1.562‐4.777] | |

| Symptoms | 3.132 | [1.949‐5.033] |

ROC analysis determined a PALLIA-10 score of 5 as the optimal cut-off point for sensitivity and specificity in predicting PC need.

3.2. Overall Survival (OS)

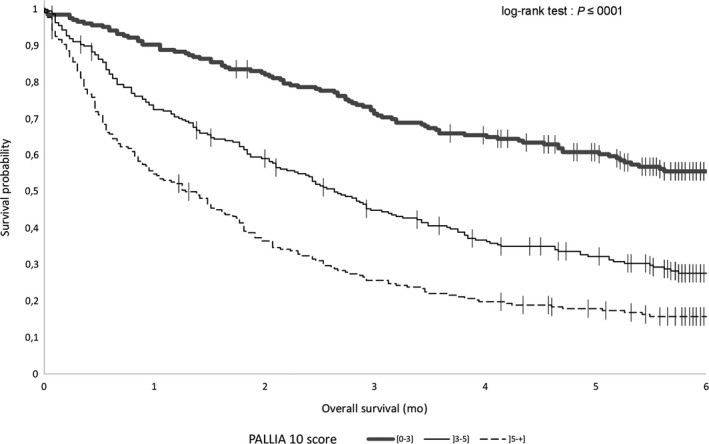

Median overall survival (OS) for palliative patients was 2.73 months (95%CI, 2.43-3.06). Analysis by PALLIA-10 score groups revealed that median OS was not reached for patients with scores ≤3, was 2.6 months (95%CI, 2.1-3.2) for scores between 4 and 5, and 1.3 months (95%CI, 0.95-1.7) for scores >5 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The PALLIA-10 score emerged as a significant prognostic factor for OS, even after adjusting for Karnofsky index, reasons for hospitalization, tumor type, opinion convergence, metastatic sites, and lymphocyte levels. Compared to scores ≤3, hazard ratios were 1.58 (95%CI 1.20-2.08) for scores 4-5 and 2.18 (95%CI 1.63-2.92) for scores >5 (Table 3). When considered as a continuous variable, PALLIA-10 score showed a significant gradient (HR = 1.18, 95%CI 1.11-1.24) after adjusting for the same variables.

Table 3.

Prognostic factors for overall survival: Multivariate Cox analysis results.

| Variables | Hazard Ratio | 95%CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PALLIA 10 Score | [0‐3] (Ref.) | ||

| ]3‐5] | 1.582 | [1.203‐2.082] | |

| ]5‐+] | 2.181 | [1.628‐2.923] | |

| Karnofsky Score | >50 (Ref.) | ||

| ≤50 | 2.084 | [1.667‐2.606] | |

| Reasons of hospitalisation | Treatment (Ref.) | ||

| Complications | 1.091 | [0.806‐1.478] | |

| Symptoms | 1.597 | [1.248‐2.044] | |

| Type of tumour | Breast (Ref.) | ||

| Head and neck | 1.747 | [1.140‐2.678] | |

| Bone and soft tissue | 1.016 | [0.641‐1.609] | |

| Lung and pleural | 1.939 | [1.403‐2.682] | |

| Digestive tract | 1.662 | [1.212‐2.279] | |

| Gynecologic | 0.894 | [0.610‐1.310] | |

| Urologic | 1.100 | [0.765‐1.582] | |

| Others | 0.908 | [0.585‐1.410] | |

| Opinion convergence (oncologist/health team/Palliative care team | At least one disagree (Ref.) | ||

| All agree | 1.672 | [1.209‐2.312] | |

| Number of metastatic sites | No metastatic site (Ref.) | ||

| One metastatic site | 0.802 | [0.535‐1.200] | |

| At least two metastatic sites | 1.311 | [0.886‐1.940] | |

| Lymphocytes | >0.7 G/l (Ref.) | ||

| ≤0.7 G/l | 1.337 | [1.093‐1.636] |

4. DISCUSSION

PREPA-10 is, to our knowledge, the first prospective multicenter study to evaluate the PALLIA-10 questionnaire as a tool for palliative care referrals and screening tool in hospitalized patients. Our findings support the PALLIA-10 as an accessible and effective tool for identifying cancer inpatients who most urgently require palliative care within comprehensive cancer centers. The questionnaire’s rapid administration and scoring are compatible with standard hospital workflows, facilitating information sharing among healthcare teams. Its successful implementation across 18 of 20 French cancer centers enhances the generalizability of our results. The PALLIA-10 was well-received and readily used by diverse healthcare professionals across all participating sites.

The lack of a unified definition for “palliative setting” complicates the implementation of PC guidelines. Relying solely on oncologist opinions for palliative status often leads to optimistic survival predictions. While prognostic factors can aid decision-making, tools like the PALLIA-10, focusing on patient needs rather than just prognosis, offer a valuable alternative. Despite the NCCN guidelines and two-step screening processes, a simpler, one-step questionnaire like PALLIA-10 is beneficial for identifying unmet palliative needs. Although recommended by SFAP in 2010, widespread adoption of the PALLIA-10 has been hindered by a lack of robust evidence supporting its relevance. This study addresses this gap, demonstrating the PALLIA-10’s utility as a decision-making instrument for initiating PC, even though it is not yet routinely used. The PALLIA-10’s strength lies in its multidimensional approach, which incorporates various critical aspects often missed in self-assessments. By employing a comprehensive semiology, the PALLIA-10 aids in determining the timeliness of palliative care intervention, reinforced by hetero-evaluation from healthcare referents beyond medical oncologists.

A key advantage of the PALLIA-10 is its consideration of not only clinical and biological factors but also psychosocial, cultural, and ethical dimensions. This holistic approach aligns with palliative care principles and, as our study shows, is statistically sound. We advocate for the use of this easily implemented, multidimensional questionnaire. While this study did not aim for psychometric validation, and further validation is warranted, the PALLIA-10 score has proven to be a predictive factor for PC team intervention. Further qualitative analysis of PALLIA-10 criteria is needed to understand the specific impact of each item, especially the innovative psychosocial criteria.

Our results indicate that both the predefined score thresholds of >3 and >5 are relevant. However, a threshold of >3 might overburden current PC team capacities within comprehensive cancer centers. Our findings, corroborated by ROC analysis, suggest a threshold of >5 is more appropriate in this setting. We found that higher PALLIA-10 scores are significantly associated with PC management, even after adjusting for metastatic status, healthcare team opinion convergence, and hospitalization reasons. Furthermore, PALLIA-10 scores reliably predict 6-month mortality, independent of other severity indicators like Karnofsky index and lymphocyte count. The increased prognostic relevance of PALLIA-10 as a continuous variable further underscores its value, with each unit increase in score correlating with reduced overall survival.

In our study, 82% of inpatients were in a palliative setting, ideally requiring PC team involvement. However, only 31% were receiving PC at study enrollment, with a median PALLIA-10 score of 6. Although 70% of patients had scores >3, indicating PC needs, only a fraction received it. This highlights a gap between identified need and service delivery, largely due to the limited capacity of PC teams. Late referrals to PC teams, often due to reluctance to acknowledge disease progression, remain a significant barrier. Implementing the PALLIA-10 could help improve referral timing within French comprehensive centers. Simultaneously, enhancing PC training for oncology and nursing teams is crucial to complement specialized PC team efforts.

Limitations of our study include its focus on cancer patients in comprehensive cancer centers, limiting generalizability. The study also focused on adult inpatients, excluding surgical patients who might also benefit from early PC. Future directions should emphasize expanding PC beyond late-stage interventions and inpatient settings, integrating early PC into outpatient care to improve quality of life.

Therefore, a PALLIA-10 threshold of >5, observed in over one-third of palliative patients, appears more practical and realistic given current PC team resources in French comprehensive cancer centers. Future randomized studies should assess the impact of PALLIA-10 implementation on patient referrals, quality of life, and caregiver burden. The PALLIA-10, with its medical and psychosocial criteria, is a promising tool for PC management initiation and prognosis. While a threshold of 3 might be too sensitive for comprehensive centers, a threshold of 5 offers a more actionable strategy for identifying patients who urgently need palliative care. Reinforcing early-stage PC interventions, including outpatient and consultative services, is also essential. Further exploration of the qualitative aspects and the impact of specific questionnaire items, particularly psychosocial factors, is warranted to optimize the use of this palliative care needs assessment scale.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yann MOLIN: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing original draft, and review; Caroline GALLAY: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Julien GAUTIER: Conceptualization Data curation Funding acquisition Methodology Project administration resources, software, supervision, Writing ‐ original draft, and writing ‐ original draft, review; Audrey LARDY‐CLEAUD: Formal analysis, writing ‐ original draft, review; Romaine MAYET: Data curation, project administration, resources, software, supervision, writing ‐ original draft, review; Marie‐Christine GRACH: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Gérard GUESDON: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Géraldine CAPODANO: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Olivier DUBROEUCQ: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Carole BOULEUC: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Nathalie BREMAUD: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Anne FOGLIARINI: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Aline HENRY: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Nathalie CAUNES‐HILARY: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Stéphanie VILLET: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Christine VILLATTE Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Véronique FRASIE: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Valérie TRIOLAIRE Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Véronique BARBAROT: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Jean‐Marie COMMER: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Agnès HUTIN: Investigation, Writing original draft, review; Gisèle CHVETZOFF: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, supervision Writing original draft, review and editing.

All authors reviewed, discussed, and agreed to their individual contributions prior to submission.

Supporting information

Click here for additional data file. (282.6KB, pdf)

Click here for additional data file. (24.9KB, tiff)

Click here for additional data file. (29.6MB, tiff)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Warm thanks are firstly addressed to the patients who were participating in this research. The authors wish to thank the staff in each participating sites for data collection and its report in the study files (staff of palliative care teams, medical assistant, service managers, and study coordinators). Special thanks are addressed to Julie DURANTI for her help during the conception of this work and to Sophie DARNIS for medical editorial assistance with this manuscript.

Molin Y, Gallay C, Gautier J, et al. PALLIA‐10, a screening tool to identify patients needing palliative care referral in comprehensive cancer centers: A prospective multicentric study (PREPA‐10). Cancer Med. 2019;8:2950–2961. 10.1002/cam4.2118

Funding information

This research was funded by the Fondation de France, grant number 00059753 and by the Centre Léon Bérard.

REFERENCES

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Click here for additional data file. (282.6KB, pdf)

Click here for additional data file. (24.9KB, tiff)

Click here for additional data file. (29.6MB, tiff)