Introduction

Globally, an estimated 21 million children require pediatric palliative care, highlighting a significant and growing need.1 In England alone, the number of infants, children, and young people living with life-limiting conditions reached approximately 86,625 in 2017/18.2,3 Pediatric palliative care differs significantly from adult palliative care due to the wider range of life-limiting conditions, greater prognostic uncertainties, unpredictable symptom trajectories, and variable disease progression timelines experienced by younger patients. Hain et al.,4 identified nearly 400 conditions that could be life-limiting in infants, children, and young people, as categorized by the Association for Children’s Palliative Care and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health.5 Advances in healthcare technology have led to longer disease trajectories for these children, necessitating pediatric palliative care for extended periods.

The primary aim of pediatric palliative care is to improve the quality of life for children and their families. A cornerstone of this holistic approach is the proactive prevention, early identification, thorough assessment, and effective management of pain and other distressing symptoms.6 Pain is a particularly prevalent and distressing symptom at the end of life.7 Studies in pediatric palliative care settings for children with progressive malignant diseases reveal pain prevalence rates exceeding 70% to 90% across various populations in the United States,8 Japan,9 Sweden,10 and the United Kingdom.11 However, pediatric pain is frequently under-diagnosed and sub-optimally treated.12,13 An American study highlighted that only 27% of children reporting pain experienced adequate pain relief.8 Despite healthcare providers’ experience in pain assessment, barriers such as concerns about side effects, abuse, and misuse of analgesics hinder effective pain management.7,14,15

Pediatric pain, regardless of its origin, is understood as a biopsychosocial phenomenon.16 Palliative pain, or “total pain,” is particularly complex, encompassing physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and practical dimensions.17 Effective pain assessment is the crucial first step towards adequate pain management in all healthcare settings.18 It is emphasized in both national19 and international guidelines,20 yet assessing pain in pediatric palliative care remains challenging. This difficulty arises from the diverse conditions of patients, varying types of pain, and often, the limited or absent verbal communication abilities of these young patients. Furthermore, despite the availability of numerous pain assessment tools, there is a notable lack of tools specifically designed and validated for pediatric palliative care for infants, children, and young people with life-limiting conditions. Therefore, appropriate tools for this population either need to be developed specifically or adapted from general tools validated in populations including children with life-limiting conditions in palliative care. A range of validated tools is essential to address the diverse developmental and communication needs within the pediatric palliative care population.

Numerous reviews have explored the development and validation of pediatric pain assessment tools across various clinical contexts.21–24 A comprehensive review by Andersen et al.25 identified 65 observational pediatric pain assessment tools. Birnie et al.26 evaluated 8 self-report pain intensity tools out of 60 identified. However, neither review focused specifically on pediatric palliative care settings. Pediatric palliative care encompasses various settings, including tertiary care facilities, emergency rooms, community health centers, hospices, and even children’s homes that support “the care of children and families facing chronic life-limiting illnesses”.27 Another review by Batalha et al.28 identified 17 pain assessment tools for children with cancer but did not offer definitive recommendations for optimal tools in this population and excluded cognitively impaired children, limiting its applicability to the broader pediatric palliative care population.

This systematic review aims to evaluate the psychometric properties of age-specific pain assessment tools used in various populations of children with life-limiting and life-threatening illnesses receiving palliative care. The goal is to provide recommendations for clinical practice based on this evidence.

Specifically, this review addresses the following questions:

- What pain assessment tools are currently used to assess pain in children with life-limiting and life-threatening illnesses receiving palliative care?

- What are the psychometric properties of these tools, including validity, reliability, and responsiveness, assessed using the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN)?

- Which pain assessment tools are most suitable for use in pediatric palliative care settings?

Methods

This systematic review and narrative synthesis examined peer-reviewed studies published in English from the inception of electronic databases (PsycINFO via ProQuest, Web of Science Core, Medline via Ovid, EMBASE, BIOSIS, and CINAHL) up to April 2021. Reference lists of included articles and relevant reviews were also manually searched. The review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) guidelines.29,30

Search Strategy

The search strategy, guided by COSMIN guidelines, incorporated construct, population, and instrument searches alongside the COSMIN psychometric properties filter (see Supplemental File 1).30–32 Keywords, text words, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and other relevant terms were combined for each database to optimize search sensitivity and specificity. Database-specific thesaurus vocabulary was used to adapt search terms. These terms were then combined with COSMIN search filters (available at http://www.cosmin.nl/).32 Search filters developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the Palliative Care Search Filter (PCSF), and relevant systematic reviews by Beecham et al. (2016) and Anderson et al. (2017)25,33–35 were also incorporated.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Study eligibility criteria were based on COSMIN guidelines30 (see Table 1). All peer-reviewed studies, regardless of design, reporting the use of pain assessment tools in pediatric palliative care settings, completed by parents, clinicians, or the patients themselves, were considered. Studies were excluded if not in English, non-scientific, not peer-reviewed, or not conducted in end-of-life, palliative, or hospice care settings. Studies using irreplicable assessment tools due to methodological ambiguity, unclear versions, or statistics were also excluded.

Table 1. Eligibility criteria for pain assessment tools in pediatric palliative care systematic review based on COSMIN guidelines.30

| Criteria | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Construct | Pain | The tool does not assess pain |

| Population | Infants, children and young people aged 0–18 with life-limiting conditions | The study sample (or an arbitrary majority, e.g. ⩾50%) does not represent infants, children and young people aged 0–18 with life-limiting conditions |

| Instrument | Pain assessment tools | Not applicable (all assessment tools are considered) |

| Psychometric properties | COSMIN defined Validity, Reliability, Responsiveness, Interpretability, Acceptability Measures | The study does not aim to evaluate one or more psychometric properties of a pain assessment tool, its development or its interpretability |

Data Extraction

Two researchers (AC and MG) independently assessed study eligibility and extracted data using a standardized form adapted from COSMIN guidelines.30 The form recorded context, population, outcomes, and psychometric properties. The COSMIN taxonomy, terminology, and definitions for health-related patient-reported outcomes were used to appraise instrument psychometric properties.36 COSMIN provides a consensus on psychometric terminology and a checklist for evaluating methodological quality regarding validity, reliability, and responsiveness.37 For synthesis, data on authors, year, country, journal, aim, sample size/characteristics, setting, design, measures, outcomes, and psychometric properties were extracted and organized into tables.

Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

Methodological quality was assessed using the COSMIN Risk of Bias Checklist.38 Each psychometric property was rated against checklist standards (boxes 3–10) for methodological flaws potentially causing bias. Each question in relevant boxes was rated “Very good,” “Adequate,” “Doubtful,” “Inadequate,” or “Not applicable.” Combining answers across 98 items (5–18 per property), each psychometric property per study received an overall rating: “Very good,” “Adequate,” “Doubtful,” or “Inadequate.” Given the lack of a gold standard for pain assessment tools in pediatric palliative care, self-report measures were considered the gold standard for criterion validity, which assesses a measure’s reflection of a gold standard.

Each psychometric property per study was rated against COSMIN guidelines for good psychometric properties (Table 2)30 and categorized as “sufficient” (+), “insufficient” (−), or “indeterminate” (?).

Table 2. Psychometric properties recorded according to COSMIN guidelines.

| Domain | Psychometric property | Aspect of a psychometric property | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reliability | The degree to which the measurement is free from measurement error | ||

| Reliability (extended definition) | The extent to which scores for patients who have not changed are the same for repeated measurement under several conditions: for example using different sets of items from the same PROM (internal consistency); over time (test-retest); by different persons on the same occasion (inter-rater); or by the same persons (i.e. raters or responders) on different occasions (intra-rater) | ||

| Internal consistency | The degree of the interrelatedness among the items | ||

| Reliability | The proportion of the total variance in the measurements which is due to ‘true’ differences between patients | ||

| Measurement error | The systematic and random error of a patient’s score that is not attributed to true changes in the construct to be measured | ||

| Validity | The degree to which a PROM measures the construct(s) it purports to measure | ||

| Content validity | The degree to which the content of a PROM is an adequate reflection of the construct to be measured | ||

| Face validity | The degree to which (the items of) a PROM indeed looks as though they are an adequate reflection of the construct to be measured | ||

| Construct validity | The degree to which the scores of a PROM are consistent with hypotheses (for instance with regard to internal relationships, relationships to scores of other instruments or differences between relevant groups) based on the assumption that the PROM validly measures the construct to be measured | ||

| Structural validity | The degree to which the scores of a PROM are an adequate reflection of the dimensionality of the construct to be measured | ||

| Hypotheses testing | Item construct validity | ||

| Cross-cultural validity | The degree to which the performance of the items on a translated or culturally adapted PROM are an adequate reflection of the performance of the items of the original version of the PROM | ||

| Criterion validity | The degree to which the scores of a PROM are an adequate reflection of a ‘gold standard’ | ||

| Responsiveness | The ability of a PROM to detect change over time in the construct to be measured | ||

| Responsiveness | Item responsiveness | ||

| Interpretability* | Interpretability is the degree to which one can assign qualitative meaning – that is, clinical or commonly understood connotations – to a PROM’s quantitative scores or change in scores. |

*Although an important property of an instrument, interpretability is not a psychometric property.

Data Synthesis and Risk of Bias Across Studies

Due to study heterogeneity, results were qualitatively summarized, considering the quantitative significance of findings. Quantitative pooling was not performed. Summarized evidence for each tool’s psychometric properties was rated against criteria for good properties and evidence strength. Risk of bias across studies was graded using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. Evidence was downgraded based on five factors: risk of bias, result inconsistency, indirectness to the target population, and result imprecision.38,39 Initial ratings by AC and GG showed fair interrater agreement (Kappa = 0.39 for psychometric properties, 0.30 for GRADE). Discrepancies were resolved through consensus meetings to achieve absolute agreement.

Final recommendations for clinical practice and research were discussed and agreed upon by clinician and researcher co-authors (AC, EJ, CL, RH, EH, IW), members of the DIPPER study. The DIPPER study is a four-phase feasibility study for a randomized clinical trial comparing transmucosal diamorphine versus oral morphine for breakthrough pain in children and young people with life-limiting conditions.

Results

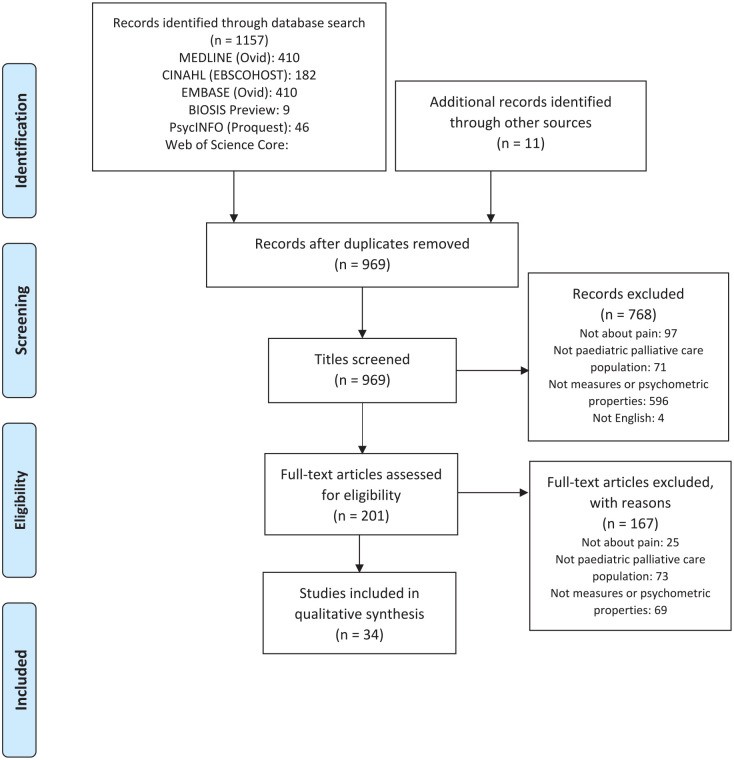

Figure 1 illustrates the study flow. The initial search yielded 1157 articles, with 11 more from manual reference searching, totaling 1168 articles screened for eligibility. After removing 199 duplicates, 969 titles and abstracts were screened. 201 full-text articles were independently reviewed by two researchers (AC and GG).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of records identified in the systematic review of pain assessment tools used in paediatric palliative care.

Further exclusion of 167 articles occurred because they did not measure pain (n = 25), the sample was not pediatric palliative care (n = 73), or no psychometric properties were evaluated (n = 69). Thirty-four articles were included in the final review.

Pain Measurement Tools and Study Populations

This review evaluated 22 pain assessment tools. Symptoms Screening in Paediatrics (SSPedi) had both self-report and proxy versions. Table 3 lists characteristics of all measures and populations for observational and self-report tools. Except for the Oral Mucositis Daily Questionnaire (OMDQ),40 no measures were disease-specific. Reflecting the distribution of life-limiting conditions, most tools were developed or validated in children with cancer. Other populations included children with hematological, neurological, surgical conditions, and those in intensive care.

Table 3. Characteristics of included measures.

| Self-report scales | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure, country of origin (reference to first article) | Acronym | Studies included | Construct(s) primary (secondary) | Age range in years unless specified | Target population | Recall period | (Sub)scale (s) (number of items) | Completion time | Training time | Response options | Range of scores/scoring | Original language |

| Adolescent paediatric Pain Tool, U.S. (Savedra et al. ) 41 | APPT | Fernandes et al. 42 ;Özalp Gerçeker et al., 2018 43 ; Madi and Badr, 44 | Pain – postoperative | I: 8–17S: 7–18 43 8–1742,44 | Surgery, Post-operative pain | Current or most recent pain | 3 (3) | 3.2–6.4 minutes | n.r. | 43 body segments;5 words- Word Graphic Rating Scale;56–67 pain descriptors | (1) Any location on the body outline; (2) no pain to worst possible pain; (3) 0–67 pain descriptors | English |

| Children’s Procedural Interview, U.S.(Pfefferbaum et al. ) 45 | CPI | Pfefferbaum et al. 45 | Pain – procedural, anxiety | I: 3–15 S: 9–15.9 | Cancer; Procedural pain | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | Semi-structured with open answers | English/ Spanish | n.r. |

| The DOLLS tool, Lebanon(Badr Zahr et al. ) 46 | DOLLS | Zahr et al. 46 | Pain – procedural | I: 4–10S: 4–10 | Cancer; Procedural pain | 0 | 1 (1) | n.r. | n.r. | 6 fabric dolls | 6 ordinal dolls | Arabic |

| Faces scales, U.S.(LeBaron and Zeltzer,) 47 | FACES | LeBaron and Zeltzer 47 ;Pfefferbaum et al. 45 | Pain – acute, anxiety | I: 6–18S: 2–6 | Cancer; Procedural pain (BMA, LP) | 0 | 1 (1) | n.r. | 1 month | 5 faces (image) | 1–5 | English |

| Faces Pain Scale – Revised, Canada(Hicks et al. ) 48 Faces Pain Scale(Bieri et al. ) 49 | FPS-R | Hicks et al. 48 ;Miro and Huguet 50 ;da Silva et al. 51 | Pain | 4–12 | Unspecified diseases | n.r. | 1 (1) | n.r. | n.r. | 6 faces (image) | 0–10 | English |

| Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale for children aged 7–12 years, Australia(Collins et al. ) 52 | MSAS 7–12 | Collins et al. 52 | Symptoms | 7–12 | Cancer | n.r. | 1 (8) | 5.8 minutes | 0 | Yes/No,3-point scales,4-point scales | Yes/No, 1–3, 0–3 | English |

| Poker Chip Tool/Pieces of HurtU.S.(Hester et al. ) 53 | PCT | West et al. 54 | Pain – procedural | I: 4.6–6.7 | Healthy, PICU | 0 | 1 (1) | n.r. | n.r. | 4 poker chips | 0–4 | English |

| Pain Squad, Canada(Stinson) 55 | n.r. | Stinson 55 ; Stinson et al. 56 | Pain – unspecified | 9–18 | Cancer | n.r. | 1 (20) | n.r.. | n.r. | Visual analogue slider scale,selectable body-map,multiple-choice question, a free-text question. | 1) 0–102) pain locations (e.g. left, right)3) multiple choices4) open answer | English |

| Pain Interference Index, Sweden (Wicksell et al. ) 57 | PII | Martin et al. 58 | Pain interference – longstanding pain | I: 10–18 S: 6–25 | Pain syndrome | 2 weeks | 1 (6) | 1–2 minutes | n.r. | 7–point scale | 0–6 | Swedish |

| Rainbow Pain Scale, Canada (Mahon et al. ) 59 | RPS | Mahon et al. 59 | Ongoing Pain | 5–10 | Cancer or haematological diseases | n.r. | 1 (5) | n.r. | n.r. | 24 colours | A box of 24 standard colours provided by Crayola | English |

| Symptom Screening in paediatrics Tool (self-report), Canada(Dupuis et al. ) 60 | SSPedi | Dupuis et al. 60 | Symptoms | 8–18 | Cancer or hematopoietic stem aaaaaaaaa transplant (HSCT) recipients | n.r. | 1 (15) | n.r. | n.r. | 5–point scale | 0 (no bother)–4 (worst bother) | English |

| Wong-Baker FACES pain rating scale, U.S. (Wong and Baker) 61 | WBS | Wong and Baker 61 ;West et al. 54 ;Holdsworth et al. 62 ;Wiener et al. 63 | Pain – unspecified | I: 3–18S: 5–13 54 7–21 63 | Hospitalised children | n.r. | 1 (1) | n.r. | n.r. | 6 one-dimensional faces | 0–5 | English |

| Oral Mucositis Daily Questionnaire, U.S.(Stiff et al. ) 64 | OMDQ | Tomlinson et al. 65 ;Manji et al. 40 | Pain and daily functioning | I: >18 S: 1–11 | Cancer | 0 | 3 (10) | n.r.. | n.r. | 5-point scale, 11-point scale | 0–4, 0–10 | English |

| Observational scales | ||||||||||||

| Measure, country of origin (reference to first article) | Acronym | Studies included | Construct(s) Primary (Secondary) | Age rangein years unless specified | Target population | Mode of administrationi.e. reported by parent/ nurse/ doctor/ researcher | Recall period | (Sub)scale (s)(number of items) | Completion time | Training time | Response options | Range of scores/scoring |

| COMFORT Scale, U.S. (Ambuel et al. ) 66 | COMFORT | Ambuel et al. 66 ;van Dijk et al., 2000 67 ;Van Dijk et al. 68 | Distress(Pain – postoperative) | I: n.r.S: 0–3 (van Dijk et al., 2000);0–368 | PICU,postoperative pain | Parent | 0–2 minutes | 8 (40) | 2 minutes | 2 hours | 5-point scale | 1–5 |

| Douleur Enfant Gustave Roussy Scale/The Gustave Roussy Child Pain Scale and revised version, France (Gauvain-Piquard et al. ) 69 | DEGR | Gauvain-Piquard et al. 69 ; Gauvain-Piquard et al. 70 ;Marec-Berard et al. 71 | Pain – acute(depression, anxiety) | I: 2–6S: 2–6 | Cancer | Nurse or researcher | n.r. | 3 (17) | 5–10 min | 2–3 hrs | 5-point scales, with 5 respective descriptions of increasing severity with reference to a provided definition of the item. | 0–4 |

| The Faces, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability pain assessment tool, U.S. (Merkel et al. ) 72 | FLACC | Merkel et al. 72 ; Manworren and Hynan 73 ;Da Silva et al. 51 | Pain | n.r. | Surgery | Researcher | n.r. | 1(5) | 5 minutes | n.r. | 3-point scale | 0–2 |

| Hétéro-Évaluation de la Douleur de l’Enfant, France (Marec-Berard et al. ) 71 | HEDEN | Marec-Berard et al. 71 | Pain – prolonged | 2–6 | Cancer | Nurse | n.r. | 3 (6) | 4.42 (5.9) min | n.r. | 3-point scale | 0–2 |

| Modified Infant Pain Scale, U.S. (Buchholz et al. ) 74 | MIPS | Buchholz et al. 74 | Pain – postoperative | 4–30 weeks | Surgery | Nurse | 0 | 1(13) | n.r. | 2 hours | 3-point scale | 0–2 |

| Objective Pain Scale, U.S., (West et al. ) 54 | OPS | West et al. 54 | Pain | 5–13 | Cancer | Parent and nurse | 0 | 1 (5) | n.r. | n.r. | 3-point scale | 0–2 |

| Procedure Behaviour Check List, U.S., (LeBaron and Zeltzer) 47 | PBCL | LeBaron and Zeltzer) 47 ; Pfefferbaum et al. 45 | Pain – acute, anxiety | 6–17 | Cancer; Procedural pain (BMA, LP) | Unspecified | 0 | 1 (8) repeated for three time periods | Time 1: 4–6 minutes, Time 2: 2–3 minutes, Time 3: 2–4 minutes | 1 month | 5-point scales, with provided definitions of each behavioural category | 1–5 |

| Pain Interference Index- Parent, U.S. (Martin et al. ) 58 | PII-P | Martin et al. 58 | Pain interference – chronic pain | 6–25 | Neurofibromatosis type 1 or Cancer | Parent | n.r. | 1 (6) | 1–2 minutes | n.r. | 7-point scale | 0–6 |

| Paediatric Pain Profile, U.K. (Hunt et al. ) 75 | PPP | Hunt et al. 75 ;Hunt et al. 76 ;Pasin et al. 77 | Pain | 1–18 | Neurological and cognitive impairments, unable to communicate through speech or any augmentative device | Parent | Retrospective | 1 (20) | n.r. | n.r. | 4-point ordinal scale | 0–3 |

| Symptom Screening in paediatrics Tool (proxy-report), Canada (Dupuis et al. ) 60 | SSPedi | Dupuis et al., 60 Hyslop et al. 78 | Symptoms | 8–18 | Cancer or hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients | n.r. | 1 (15) | n.r. | n.r. | 5-point scale | 0 (no bother)–4 (worst bother) | English |

I: intended population where tool was first published; S: populations reported in subsequent studies where tool was validated; PICU: paediatric intensive care unit; n.r.- not reported; APPT: Adolescent Paediatric Pain Tool; CPI: Children’s Procedural Interview; DEGR scale: Douleur Enfant Gustave Roussy; FPS-R: Faces Pain Scale-Revised; FLACC scale: Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability scale; HEDEN scale: Hétero Evaluation Douleur Enfant scale; MIPS: Modified Infant Pain Scale; MSAS: Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale; OMDQ: Oral Mucositis Daily Questionnaire; OPS: Objective Pain Scale; PBCL: Pain Behaviour Check List; PCT: Poker Chip Tool; PII: Pain Interference Index; PII-P: Pain Interference Index-Parent; PPP: Paediatric Pain Profile; r: Pearson product moment correlation coefficient; RPS: Rainbow Pain Scale; SSPedi: Symptom Screening in Paediatrics; WBS: Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale; U.K.: United Kingdom; U.S. : United States; NF-1: neurofibromatosis type 1.

Feasibility of Use

The feasibility of pain assessment tools is crucial in pediatric palliative care. This review assessed feasibility by evaluating tool types, ease of administration, completion time, training needs, recall period, instrument length, scoring simplicity, calculation, and standardization. Given the diverse patient conditions and needs in palliative care, no single tool is universally feasible.

Completion time was reported for most self-report tools, ranging from 1 to 10 minutes, except for the Paediatric Pain Profile (PPP). Completion times for observational tools were largely unreported. Training and recall periods were also generally underreported. Most tools used point scales or ordinal responses. The Adolescent Paediatric Pain Tool (APPT), Children’s Procedural Interview (CPI), and Pain Squad included semi-structured or open-ended response options. Tools with ordinal response systems were generally easier to standardize, calculate, and administer. Pain Squad and Symptoms Screening in Paediatrics (SSPedi) were notable for their development as electronic, mobile-device-compatible versions, enhancing their feasibility in modern clinical settings.

Methodological Quality of Psychometric Properties

Methodological quality ratings for each psychometric property per study are detailed in Supplemental File 2. Internal structure was assessed through content validity, structural validity, cross-cultural validity, and internal consistency reporting. Internal consistency was the most frequently reported property. Hypothesis testing, convergent, and divergent validity were also commonly described. Reliability measures were often reported, but studies using dichotomous, nominal, or ordinal scores frequently lacked kappa calculations and weighting schemes,43 or reported only Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients without kappa.40,65,71 This significantly weakened the strength of evidence. Only one study reported intrarater agreement.76

Most studies provided limited psychometric evidence, with none reporting on all four domains or more than half of the psychometric properties of interest. Psychometric property results and methodological quality ratings are summarized in Supplemental File 2, and a qualitative summary is in Table 4.

Table 4. Overall ratings of qualitatively summarized psychometric properties and quality of the evidence per pain measure.

| Measure | Content validity | Structural validity | Cross-cultural validity | Internal consistency | Hypotheses testing | Criterion validity | Reliability | Measurement error | Responsiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APPT | ? (Low) | NA | ? (Low) | + (Moderate) | NA | NA | + (High) | NA | NA |

| COMFORT | + (Moderate) | + (Moderate) | NA | + (High) | + (Low) | NA | + (High) | NA | + (Low) |

| CPI | NA | NA | NA | + (Moderate) | − (Moderate) | NA | NA | NA | − (Moderate) |

| DEGR | NA | + (High) | NA | + (High) | − (Moderate) | NA | + (Moderate) | NA | − (Moderate) |

| DOLLS | NA | NA | NA | NA | + (Moderate) | + (High) | NA | NA | + (Moderate) |

| FLACC | NA | NA | NA | + (Moderate) | + (Moderate) | + (Low) | + (High) | NA | + (Moderate) |

| Le Baron and Zeltzer Faces Scale | NA | NA | NA | + (High) | ? (Very low) | NA | NA | NA | ? (Very low) |

| FPS-R | NA | NA | + (Very low) | NA | + (Moderate) | − (Moderate) | NA | NA | + (Very low) |

| HEDEN | NA | NA | NA | − (Moderate) | − (Moderate) | NA | − (Very low) | NA | − (Moderate) |

| MIPS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | + (Very low) | − (Very low) | NA | NA |

| MSAS (7–12) | NA | NA | NA | − (Moderate) | NA | + (Moderate) | − (Moderate) | NA | NA |

| OMDQ | NA | NA | NA | NA | + (High) | NA | + (Low) | NA | + (High) |

| OPS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | − (Very low) |

| Pain Squad | + (Low) | NA | NA | + (High) | − (High) | NA | NA | NA | − (Moderate) |

| PBCL | NA | NA | NA | + (Very low) | − (Moderate) | − (Moderate) | ? (Low) | NA | − (Low) |

| PCT | NA | NA | NA | NA | + (Very low) | − (Low) | ? (Very low) | NA | − (Low) |

| PII | NA | NA | NA | + (Moderate) | − (Moderate) | NA | NA | NA | − (Moderate) |

| PII (PII-P) | NA | NA | NA | + (Moderate) | NA | − (Moderate) | NA | NA | NA |

| PPP | + (Very low) | NA | + (High) | + (High) | − (Moderate) | + (Moderate) | + (Moderate) | NA | + (Low) |

| RPS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | + (Moderate) | + (Low) | NA | + (Low) |

| SSPedi | NA | NA | NA | + (Moderate) | − (Low) | NA | + (Moderate) | NA | − (Low) |

| WBS | NA | NA | NA | NA | + (High) | + (High) | ? (Low) | NA | + (High) |

+: sufficient overall rating psychometric properties; ?: indeterminate overall rating psychometric property; −: insufficient overall rating psychometric property; NA: information not available; APPT: Adolescent Paediatric Pain Tool; CPI: Children’s Procedural Interview; DEGR scale: Douleur Enfant Gustave Roussy; FPS-R: Faces Pain Scale-Revised; FLACC scale: Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability scale; HEDEN scale: Hétero Evaluation Douleur Enfant scale; MIPS: Modified Infant Pain Scale; MSAS: Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale; NA: not available; OMDQ: Oral Mucositis Daily Questionnaire; OPS: Objective Pain Scale; PBCL: Pain Behaviour Check List; PCT: Poker Chip Tool; PII: Pain Interference Index; PII-P: Pain Interference Index-Parent; PPP: Paediatric Pain Profile; r: Pearson product moment correlation coefficient; RPS: Rainbow Pain Scale; rs: Spearman correlation coefficient; SSPedi: Symptom Screening in Paediatrics; τ: Kendall’s tau (τ) correlation coefficient; WBS: Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale.

Content validity was assessed in five studies for four tools, with generally appropriate evaluations of relevance and comprehensibility by patients and experts. Structural validity, assessed in four studies for two tools, generally used confirmatory or exploratory factor analysis, except for one study using Principal Component Analysis.66 Cross-cultural validity, assessed in four studies for three tools, utilized independent translation, back-translation, or expert committees. Internal consistency was assessed in 14 studies for 16 tools, generally using Cronbach’s alpha appropriately. Hypothesis testing was performed for all tools except RPS,59 generally using convergent and divergent validity appropriately. Criterion validity was assessed in 14 studies for 14 tools, generally assessing concurrent or predictive validity. Reliability was assessed in 19 studies for 14 tools, generally using test-retest reliability, interrater agreement, and intrarater agreement appropriately.

Recommended Pain Assessment Tools for Clinical Practice

Based on this systematic review, specific pain assessment tools are recommended for use in pediatric palliative care, balancing feasibility and psychometric properties.

Self-Report Tool: Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R)

The Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R) is recommended as a self-report measure for pain assessment in pediatric palliative care. This tool features six facial drawings arranged horizontally, from a neutral face (score 0) to a face indicating maximum pain (score 10). Validated in a clinical sample of children aged 5 to 17 hospitalized with cancer, the FPS-R has demonstrated strong criterion and construct validity. While its internal structure was not extensively examined, the cross-cultural validity was supported through the development of the Catalan version, although cultural validation post-translation was not conducted. The FPS-R is available in numerous languages, enhancing its broad applicability across diverse populations.

Observational Tools: FLACC Scale/FLACC-Revised and Paediatric Pain Profile (PPP)

For observational pain assessment, the Faces, Legs, Activity, Cry, and Consolability (FLACC) scale and the Paediatric Pain Profile (PPP) are recommended tools in pediatric palliative care.

-

FLACC Scale: This scale assesses pain intensity by scoring five behavioral categories: Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, and Consolability. Each category is scored from 0 to 2, resulting in a total score range of 0-10. Descriptors for each item represent pain-indicative behaviors, with score levels (0, 1, or 2) indicating increasing pain intensity. Initially developed for distress measurement, FLACC is widely used for postoperative pain assessment in children aged 4-17. Versions in English, Arabic, and Brazilian Portuguese were reviewed, demonstrating good internal consistency and reliability. The Brazilian Portuguese version showed sufficient internal consistency in children aged 7-17. The original English version exhibits high interrater agreement.

-

Paediatric Pain Profile (PPP): The PPP is a 20-item rating scale for children aged 1-18 with neurological and cognitive impairments. Each item is rated on a four-point scale, from ‘not at all’ to ‘a great deal,’ over a given period, with total scores ranging from 0 to 60. The Brazilian version underwent content validation with healthcare professionals and caregivers, achieving high clarity ratings. The PPP demonstrates very good criterion validity against numerical rating scales and good reliability, internal consistency, and insufficient convergent validity with physiological measures. Reliability has been confirmed through interrater agreement, intrarater agreement, and test-retest reliability across studies.

The FLACC-Revised (FLACC-R) scale,79 although not directly reviewed in this study, is also recommended for children who are non-verbal or cognitively impaired. FLACC-R is an adaptation of the FLACC scale, incorporating additional pain behaviors common in non-verbal or cognitively impaired children, based on parent reports within each category.

Discussion

Key Findings and Implications

This systematic review is the first to comprehensively evaluate pain assessment tools specifically for pediatric palliative care, examining their psychometric properties and feasibility to provide evidence-based recommendations for clinical practice. The findings recommend the FPS-R for self-report and the FLACC scale/FLACC-R and PPP for observational pain assessment in this setting.

Given the subjective nature of pain, self-reporting should always be the primary method of pain assessment when possible.18 In pediatric palliative care, where children are often cared for at home or in non-clinical settings, parent or caregiver reports are crucial and should be considered the next best option. Our recommendations prioritize tools validated with high correlations between parent and self-reports. We emphasize the use of pain assessment tools with sufficient content validity and internal consistency to accurately reflect pain intensity in children with life-limiting conditions. Tools with high-quality evidence of insufficient psychometric properties should be avoided in this population until validated modifications are available.

Strengths and Limitations of the Review

This review’s strength lies in its rigorous methodology, providing a critical appraisal of the existing literature on the reliability, validity, responsiveness, and feasibility of pain assessment tools in pediatric palliative care. Such systematic reviews are essential for clinicians making complex decisions about pain management and tool selection for diverse patient populations.

However, this study acknowledges the inherent limitations of the COSMIN checklist, as noted by Coombes et al.,80 including issues with content validation, interrater reliability, and ambiguities in reporting quality. This review addressed feasibility by examining intrinsic tool characteristics (Table 3), such as administration mode, completion time, and validation settings. Extrinsic factors like patient and clinician comprehension, copyright, and regulatory approvals were not thoroughly examined due to limited data. Interpretability was also not extensively reviewed as most tools focused on unidimensional pain intensity measurement.

Pain assessment tools aim to standardize pain reporting and guide clinical decisions in a generalizable and comprehensible manner. The tools recommended here are based on a balance of feasibility and psychometric properties but may not be optimal for all types of pain in pediatric palliative care, such as breakthrough pain.81

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

Despite the numerous pain assessment tools available, this review highlights a significant gap in validation studies specifically within pediatric palliative care settings. Many feasible scales lack sufficient validation evidence for use in children with life-limiting conditions. Validation data is crucial for selecting effective pain assessment tools in this population. Given the profound impact of pain on children’s quality of life, especially at the end of life, standardized pain assessment implementation is urgently needed. Future research should focus on robust clinical validation of pain assessment tools in pediatric palliative care to improve long-term pain management and quality of life for these children.

Supplemental Material

sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211049309 – Supplemental material for Pain Assessment Tools In Paediatric Palliative Care: A systematic review of psychometric properties and recommendations for clinical practice

Click here for additional data file. (455.3KB, pdf)

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211049309 for Pain assessment tools in paediatric palliative care: A systematic review of psychometric properties and recommendations for clinical practice by Adrienne YL Chan, Mengqin Ge, Emily Harrop, Margaret Johnson, Kate Oulton, Simon S Skene, Ian CK Wong, Liz Jamieson, Richard F Howard and Christina Liossi in Palliative Medicine

sj-pdf-2-pmj-10.1177_02692163211049309 – Supplemental material for Pain assessment tools in paediatric palliative care: A systematic review of psychometric properties and recommendations for clinical practice

Click here for additional data file. (1.2MB, pdf)

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-pmj-10.1177_02692163211049309 for Pain assessment tools in paediatric palliative care: A systematic review of psychometric properties and recommendations for clinical practice by Adrienne YL Chan, Mengqin Ge, Emily Harrop, Margaret Johnson, Kate Oulton, Simon S Skene, Ian CK Wong, Liz Jamieson, Richard F Howard and Christina Liossi in Palliative Medicine

Footnotes

Author’s note: Kate Oulton is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Nurse and Midwife Research Leader.

Author contributions: IW is the Chief Investigator of the DIPPER study and conceived the project and takes overall responsibility for the conduct of the study. AYLC was involved in the study design, acquisition, data screening, data extraction, quality assessment, qualitative synthesis or interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript with input from all authors. GMG was involved in the cross checking of data screening, data extraction, quality assessment and qualitative synthesis. LJ was involved in planning and study design, contributed to the search strategy and commented on various drafts of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme (Grant Reference Number PB-PG-0317-20036). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

ORCID iDs: Simon S Skene https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7828-3122

Liz Jamieson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3667-0423

Richard F Howard https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9271-0074

Christina Liossi https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0627-6377

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

[References are in the original article and should be kept in the final output]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211049309 – Supplemental material for Pain assessment tools in paediatric palliative care: A systematic review of psychometric properties and recommendations for clinical practice

Click here for additional data file. (455.3KB, pdf)

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211049309 for Pain assessment tools in paediatric palliative care: A systematic review of psychometric properties and recommendations for clinical practice by Adrienne YL Chan, Mengqin Ge, Emily Harrop, Margaret Johnson, Kate Oulton, Simon S Skene, Ian CK Wong, Liz Jamieson, Richard F Howard and Christina Liossi in Palliative Medicine

sj-pdf-2-pmj-10.1177_02692163211049309 – Supplemental material for Pain assessment tools in paediatric palliative care: A systematic review of psychometric properties and recommendations for clinical practice

Click here for additional data file. (1.2MB, pdf)

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-pmj-10.1177_02692163211049309 for Pain assessment tools in paediatric palliative care: A systematic review of psychometric properties and recommendations for clinical practice by Adrienne YL Chan, Mengqin Ge, Emily Harrop, Margaret Johnson, Kate Oulton, Simon S Skene, Ian CK Wong, Liz Jamieson, Richard F Howard and Christina Liossi in Palliative Medicine