Abstract

Objective:

Point-of-care tools (PoCTs) are essential resources that offer immediate, evidence-based information to support patient care decisions and clinical procedures at the point of care. While numerous PoCTs are available and marketed to registered nurses, whose practice demands unique information access, there is a notable gap in the rigorous evaluation of these nursing-focused PoCTs. This paper addresses this gap by detailing the development and application of an evaluation rubric specifically designed for Nursing Point Of Care Tools.

Case Presentation:

To address the need for a standardized evaluation method, our team developed a comprehensive rubric. This rubric incorporates key evaluation criteria focusing on: the breadth and depth of content, the coverage of critical nursing topics, the transparency of the underlying evidence, user perception of the tool, and the extent to which the PoCT can be customized to meet specific nursing practice needs. We applied this rubric to five prominent PoCTs frequently cited in nursing literature and identified as relevant by nursing leadership: ClinicalKey for Nursing, DynaMed, Lippincott’s Advisor and Procedures, Nursing Reference Center Plus, and UpToDate. Our analysis using the rubric revealed varying strengths across the platforms. Lippincott’s Advisor and Procedures demonstrated the most extensive coverage of nursing diagnoses, while ClinicalKey for Nursing excelled in content related to nursing interventions and patient outcomes. Nursing Reference Center Plus offered a robust, well-rounded coverage of nursing terminology and a wide array of nursing-specific topics. In contrast, DynaMed and UpToDate, while exhibiting greater transparency in disclosing potential conflicts of interest, showed comparatively limited coverage of nursing-specific terminology, core nursing content, and nursing care processes.

Conclusion:

Our evaluation concluded that none of the five nursing point of care tools comprehensively satisfied all evaluation criteria within our rubric. The developed rubric serves as a valuable instrument for highlighting the specific strengths and weaknesses inherent in each PoCT. This detailed comparative analysis empowers institutions to make informed decisions about PoCT selection, aligning choices with their unique priorities and budgetary constraints. Based on our findings, we recommend that healthcare organizations consider a dual approach: licensing a dedicated nursing PoCT alongside a broader, more general PoCT such as DynaMed or UpToDate. This strategy aims to deliver comprehensive, evidence-based patient care resources and effectively address the diverse information needs of the entire nursing staff.

Keywords: point-of-care tool, evaluation rubric, nursing, decision-making, nursing point of care tools

BACKGROUND

In the fast-paced environment of modern healthcare, point-of-care tools (PoCTs) serve as indispensable resources, providing rapid answers to critical clinical questions right at the bedside. Each tool, however, comes with its own set of strengths and weaknesses. Given the significant investment required for these resources and the ever-present budget limitations faced by hospitals and libraries, the question becomes paramount: which PoCTs are most effective for delivering evidence-based nursing care? Health sciences librarians, with their specialized expertise in information resources, are uniquely positioned to evaluate the quality and suitability of PoCTs for specific user groups, including nurses [1].

Previous evaluations of PoCTs have predominantly focused on their utility within the medical discipline or across healthcare in a general sense. A significant gap exists in research specifically comparing PoCTs in terms of their ability to meet the distinct information needs of nurses. The daily workflow of nurses differs fundamentally from that of physicians and advanced practice nurses. While physicians and advanced practitioners often concentrate on diagnostics and treatment strategies, bedside nurses require immediate access to the most current information on hospital policies, clinical procedures, and best practices to effectively plan and execute nursing interventions [2]. Therefore, a PoCT truly designed to support nursing practice must deeply consider and address these specific informational requirements [3]. The need for targeted nursing point of care tools is evident in the daily demands of patient care.

This case report details the development and pilot testing of a novel evaluation rubric explicitly designed for nursing point of care tools. This rubric was constructed to assess PoCTs based on several key dimensions critical to nursing practice: the relevance and depth of content, the breadth of coverage across diverse nursing topics, the transparency and rigor of the underlying evidence, user perceptions of usability and utility, and the degree of customization available to tailor the tool to specific nursing contexts.

CASE PRESENTATION

The University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) has utilized Nursing Reference Center Plus (NRC+) as a core resource since 2009. In 2019, the hospital’s Nursing Advanced Practice and Research Council initiated a review process to re-evaluate available nursing PoCTs. Their aim was to identify the tools that best aligned with the evolving needs of their nursing staff. A librarian, serving as an ad hoc member of the council, brought this request to the attention of the UIC nursing librarian team. Recognizing the importance of evidence-based resource selection, the nursing librarians took the lead in this evaluation.

After a thorough review of the existing literature, the nursing librarians discovered a lack of evaluation rubrics specifically tailored for nursing point of care tools. Consequently, they decided to develop and pilot test their own rubric. For the evaluation, they selected three PoCTs already licensed and actively used within the hospital system: DynaMed and NRC+ from EBSCO, and UpToDate from Wolters Kluwer. To broaden the scope of the evaluation and include leading nursing-specific resources, they also secured trial access to ClinicalKey for Nursing (CK Nursing) from Elsevier and Lippincott Advisor and Procedures (Lippincott), informed by recommendations from nursing leadership. This selection aimed to provide a comprehensive comparison of both general and nursing-specific point of care tools.

METHODS

Rubric Development

The primary goal of this study was to evaluate PoCTs specifically from the perspective of their suitability and effectiveness for nurses. To achieve this, the investigators embarked on developing a robust and relevant evaluation rubric. This process involved synthesizing criteria from previously established rubrics used for evaluating healthcare resources [4–7]. These existing frameworks provided a foundation of best practices in resource evaluation. To ensure the rubric was specifically attuned to the nuances of nursing practice and information needs, the investigators actively sought and incorporated input from the Nursing Council. This collaborative approach ensured that the final rubric was not only rigorous but also highly relevant to the target users.

The final rubric (Appendix 1) encompassed criteria across five core domains:

- Content Types: This section assessed the variety of content formats available within each PoCT, such as clinical summaries, care plans, patient education materials, guidelines, and multimedia resources.

- Breadth of Coverage for Nursing: This domain focused on the extent to which each PoCT covered essential nursing topics, including diagnoses, interventions, outcomes, and specialized areas of nursing practice.

- Transparency of Evidence: This critical aspect evaluated how clearly each PoCT communicated the evidence base for its recommendations, including methods for grading evidence, disclosure of potential biases or conflicts of interest, and currency of information.

- User Perceptions: This section aimed to capture the subjective user experience, assessing factors such as ease of navigation, clarity of information display, relevance of search results, and overall ease of use.

- Customization of Content: This domain explored the flexibility of each PoCT in allowing users to personalize their experience, such as saving content, setting up alerts, tracking continuing education units (CEUs), and accessing mobile applications.

Pilot Testing

To rigorously test the rubric’s functionality and applicability, a pilot study was conducted. Four investigators independently applied the rubric to each of the five selected PoCTs. Data extraction took place between February and April 2020, with investigators using a standardized Microsoft Excel template to record their findings. For most criteria, a binary “yes/no” response was used to indicate whether the criterion was present and identifiable within the PoCT. The “yes” indicated that the investigator was able to locate the specific feature or content type within the platform. For the “User Perception” section, a Likert scale (ranging from 5 = excellent to 1 = poor) was employed to capture nuanced ratings of usability and information presentation.

To specifically assess the “Coverage of Nursing Topics,” investigators conducted targeted searches using the standardized NANDA-I, Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC), and Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) terminologies. Search strategies, including phrase searching with quotation marks, were determined at the discretion of each investigator to optimize retrieval of relevant content. For each terminology search, investigators reviewed the first ten search results to determine if they were relevant and useful to a bedside nurse. A “yes” was recorded in the rubric if the search results were deemed relevant.

To identify “Content Types,” investigators systematically explored each PoCT’s interface, examining tab menus, sidebar navigation, and the information displayed during terminology searches. Content types were marked “yes” if investigators could locate them anywhere within the PoCT, demonstrating their presence within the resource.

“Transparency of Evidence” was evaluated by examining how evidence-based content was integrated into PoCT summaries. Investigators looked for explicit statements about evidence grading methodologies and disclosures or policy statements regarding the process of content development and potential conflicts of interest. “Customization of Content” features were assessed by exploring personal account settings and mobile app functionalities, looking for options such as content saving, email alerts, CEU tracking, mobile app availability (and offline access), and feature parity between web and app versions.

Following individual data extraction, all collected data were compiled into a master spreadsheet. The team then convened for collective discussion to resolve any discrepancies or disagreements in their individual assessments. After reviewing all five PoCTs, quantitative analyses were performed. For the “Content,” “Transparency,” and “Customization” sections, the total number of “yes” responses (indicating criterion presence) were summed for each PoCT. For “Coverage of Nursing Topics,” the percentage of relevant results was calculated for each of the NANDA, NIC, and NOC terminologies. This was done by summing the number of terminologies found by each investigator, dividing by the total possible findings, and then averaging across the four investigators to account for inter-rater variability. The “User Perception” scores were calculated by averaging the Likert scale ratings across all criteria within that section to generate an overall usability score for each PoCT.

RESULTS

The results from the rubric pilot testing are presented using descriptive statistics to summarize the findings across the five nursing point of care tools. Tables 1, 2, and Table 3 (Table 3 – Appendix B) illustrate the number of investigators (ranging from 0 to 4) who successfully identified each content, transparency, and customization criterion as defined in the rubric. For the “Coverage of Nursing Terminology,” results are presented as the average percentage of relevant search results. “User Perception” is graded on a composite scale derived from the Likert ratings. Complete agreement among all four investigators (indicated by a score of 4) signifies that the information was readily and unambiguously identified within the PoCT. Disagreement between investigators (scores less than 4) suggests that not all investigators were able to locate the required information or that there was variability in judgments about the relevance of search results.

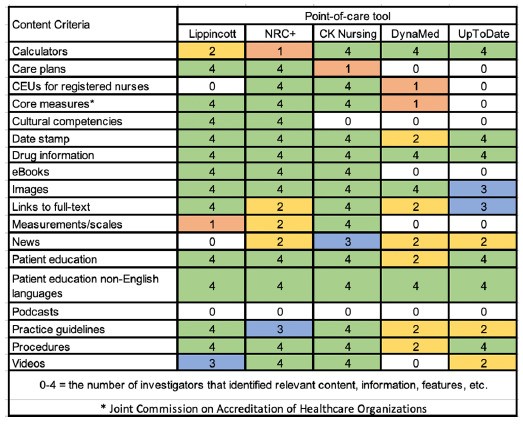

Table 1. Content Types.

| Alt Text: Table 1 showing the content types available in each point-of-care tool evaluated, including ClinicalKey for Nursing, DynaMed, Lippincott Advisor, Nursing Reference Center Plus, and UpToDate. Content types listed are: Disease summaries, Diagnosis summaries, Drug monographs, Procedures, Differential diagnosis, Guidelines, Care plans, Patient education, Clinical calculators, Lab manuals, Anatomy, Images, Videos, Cultural competencies, Continuing education, Point-of-care CME, Journal articles, and Book chapters. The table displays the number of investigators who found each content type in each tool. |

Table 2. Transparency Criteria.

|

||

|—|

| Alt Text: Table 2 detailing the transparency criteria assessed for each nursing point of care tool: ClinicalKey for Nursing, DynaMed, Lippincott Advisor, Nursing Reference Center Plus, and UpToDate. Transparency criteria include: Evidence grading, References, Currency of information, Update frequency, Conflict of interest policy, Editorial board listed, Nurse editors listed, Author credentials provided, and Peer-review process described. The table shows the number of investigators who identified each transparency criterion in each tool. |

Content

All evaluated point of care tools offered content relevant to nursing practice (Table 1). However, the PoCTs specifically designed for nursing – ClinicalKey Nursing, Lippincott, and NRC+ – presented a significantly broader and more diverse range of content directly applicable to the information needs of bedside nurses. ClinicalKey Nursing achieved the highest content score, with all four investigators identifying relevant content for fourteen out of the eighteen assessed criteria. Lippincott and NRC+ closely followed, with full investigator agreement on twelve of the criteria. In contrast, DynaMed and UpToDate showed less investigator agreement and fewer criteria identified overall, indicating a narrower focus on nursing-specific content. Notably, cultural competencies were minimally covered across ClinicalKey Nursing, DynaMed, and UpToDate, highlighting a potential area for improvement in these platforms.

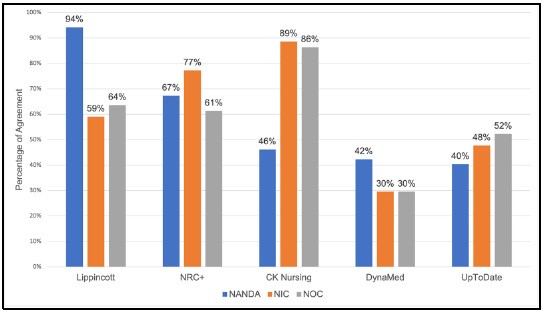

Coverage of Nursing Terminology

Figure 1 visually represents the level of agreement among investigators regarding the relevance of search results for standardized nursing terminologies (NANDA-I, NIC, NOC). The results are averaged across the four investigators to provide a composite view. NRC+ and Lippincott demonstrated the broadest relevant coverage, with all terminology categories scoring above 50%. Lippincott exhibited the highest level of agreement for relevant coverage of nursing diagnoses (NANDA-I). ClinicalKey Nursing showed stronger relevant coverage for nursing interventions (NIC) and patient outcomes (NOC) compared to the other PoCTs. DynaMed and UpToDate, in comparison, showed lower levels of relevant coverage across all nursing terminologies, indicating a less nursing-centric approach in their content organization and search algorithms.

Figure 1.

Alt Text: Figure 1 is a bar chart comparing the percentage of relevant search results for Nursing Terminology across five point-of-care tools: ClinicalKey for Nursing, DynaMed, Lippincott Advisor, Nursing Reference Center Plus, and UpToDate. The chart displays results for NANDA (Nursing Diagnoses), NIC (Nursing Interventions Classification), and NOC (Nursing Outcomes Classification). Nursing Reference Center Plus and Lippincott Advisor show the highest percentage of relevant results across all terminologies, while DynaMed and UpToDate show lower percentages. ClinicalKey for Nursing shows a higher percentage for NIC and NOC compared to NANDA.

Nursing Terminology.

Transparency

The transparency criteria evaluated the extent to which each PoCT explicitly conveyed information regarding content currency, the methodologies used for grading and synthesizing evidence, and the mechanisms in place to identify and mitigate potential biases (Table 2). DynaMed achieved the highest score in transparency, with all four investigators locating seven out of the nine transparency criteria. UpToDate followed, with five criteria consistently identified by all investigators. In stark contrast, Lippincott showed limited transparency in these areas, with full investigator agreement on only one criterion. Furthermore, for five of the transparency criteria, none of the investigators found any relevant content within Lippincott, and only one investigator located information for two additional criteria, highlighting a significant gap in transparency for this PoCT.

Customization

Investigator agreement regarding customization criteria was generally lower compared to the other rubric categories, indicating greater variability in the presence and discoverability of these features (Table 3 – Appendix B). Customizable features assessed included the ability to save content, set up email alerts, track CEUs, access mobile apps (and offline capabilities), and feature consistency between app and web versions. Personal account customizations were not universally available across all PoCTs. Overall, DynaMed and NRC+ ranked higher in customization, with three or four investigators identifying customization features for six of the seven criteria. In contrast, for both ClinicalKey Nursing and Lippincott, no investigators found features for three of the customization criteria, suggesting limited customization options in these platforms.

User Perception

The investigators independently evaluated user perception using a Likert scale, and the final results represent a composite of all investigators’ opinions. Aspects reviewed included ease of navigation, clarity of information display, relevance of information, and ease of searching. DynaMed received slightly higher ratings for its content summaries, indicating a positive user experience in this area. Overall, NRC+ achieved the highest user perception score, with 21.75 out of a possible 30 points, followed by Lippincott (20.5 points), DynaMed (19 points), ClinicalKey Nursing (18.5 points), and UpToDate (17.5 points). While NRC+ was rated highest, the scores were relatively close across all platforms, suggesting a generally acceptable user experience across the evaluated PoCTs.

DISCUSSION

The implementation of a rubric to evaluate nursing point of care tools offers a transparent and systematic process grounded in standardized criteria. The criteria were not only derived from existing literature on resource evaluation [4–7] but were also specifically tailored to the nuances of nursing practice and terminology through expert input. Based on established rubrics, evaluation tools, and the investigators’ collective expertise in health librarianship, we believe this rubric provides a robust framework for examining the nursing-focused content and coverage of PoCTs. However, it’s important to acknowledge that certain factors, such as cost and overlap in content coverage across different resources, are inherently difficult to incorporate directly into a rubric. We strongly recommend that institutions consider these and other institution-specific factors in their comprehensive decision-making processes when selecting PoCTs.

The observed physician-centric approach in the presentation of information in some of the PoCTs, particularly DynaMed and UpToDate, highlighted a potential disconnect in understanding how nurses approach patient care. This is evidenced by the limited coverage of nursing-specific subjects in DynaMed and UpToDate (as shown in Figure 1) and the relatively limited involvement of nurse authors in PoCT content development within ClinicalKey Nursing. In general, DynaMed and UpToDate leaned more towards medical diagnoses and treatments, while the nursing-focused PoCTs placed greater emphasis on nursing procedures, care planning, and continuity of care, aligning more closely with the typical workflow and information needs of bedside nurses.

Content

The presentation and delivery of content varied considerably across the evaluated PoCTs. Investigators specifically looked for unique nursing-related content types within each platform, such as standardized care plans, patient education handouts available in multiple languages, and continuing education opportunities designed for nurses. A notable observation was that many PoCTs lacked seamless cross-linking between their own platforms and related external resources, potentially hindering end-user access to full-text articles or supplementary materials. Vendors should prioritize automatic linking of licensed content to enhance the discoverability of full-text and other relevant resource types. Lippincott, for example, effectively integrates its proprietary content, promoting discoverability between its Advisor and Procedures products. In contrast, other vendors may require subscribers to manually request or enable linking between different product components. For instance, the library at UIC had to periodically request that citations from CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) be integrated into NRC+ search results, despite holding separate licenses for both NRC+ and CINAHL. Evaluating the ease of accessing linked resources and the seamlessness of content integration could be a valuable addition to future iterations of the rubric.

Investigators also noted that search results did not consistently prioritize content directly relevant to immediate patient care needs. For example, search results in Lippincott sometimes included the NANDA-I definitions eBook, while NRC+ results included citations and full-text articles from the CINAHL database, and ClinicalKey Nursing results included MEDLINE citation records. While these results were thematically relevant to the search query, they did not always directly support point-of-care patient management. Search algorithms within PoCTs need further refinement to prioritize actionable, patient-care-focused content, such as care plans and clinical procedures, especially within PoCTs that offer a wide array of content types supporting nursing practice.

The availability of Continuing Education Units (CEUs) within the PoCTs varied significantly. ClinicalKey Nursing and NRC+ offered CEUs specifically for registered nurses, while other platforms either required additional subscriptions or lacked CEU offerings tailored to registered nursing. While DynaMed and UpToDate include continuing education for nurse practitioners, this focus does not fully acknowledge the diverse scope of registered nursing practice. Vendors should consider expanding and integrating more CEUs specifically designed for registered nurses as a core component of nursing point of care tools. This would serve to strengthen ongoing professional development within the nursing workforce [13,14].

Finally, investigators explored the presence of novel content types within the PoCTs, seeking to identify innovative formats that could enhance user engagement and learning. One medium examined was podcasts; however, none of the evaluated PoCTs produced or integrated podcast content. The investigators encourage vendors to consider expanding into emerging content mediums like podcasts to provide nurses with alternative avenues for knowledge acquisition and professional development, catering to diverse learning preferences and on-the-go information access needs.

Coverage of Nursing Terminology

The investigators’ use of standardized nursing terminologies – NANDA-I, NIC, and NOC – provided a structured and consistent approach to evaluating the coverage of nursing-specific topics across the PoCTs. This methodology standardized the process of seeking information relevant to core nursing concepts. The analysis revealed an imbalance in the coverage of the three terminologies across different platforms. ClinicalKey Nursing exhibited comparatively weaker coverage of nursing diagnoses (NANDA-I), while Lippincott showed areas for improvement in its coverage of nursing interventions (NIC) and patient outcomes (NOC). For these platforms to be truly comprehensive resources for nursing practice, further development is needed to ensure robust coverage across the full spectrum of the nursing care process, from diagnosis to intervention to outcome evaluation.

Another challenge encountered was the task of distinguishing nursing-specific terminology from broader medical terminology, particularly within DynaMed and UpToDate. While the investigators acknowledge the established use of DynaMed and UpToDate by nurses for general clinical information, their comparatively limited coverage of explicitly nursing-focused subject matter is a notable finding.

Finally, the investigators observed inconsistencies in the presentation of standardized terminologies within the PoCTs. Some platforms presented NANDA-I, NIC, and NOC topics within the broader context of disease or condition summaries. Others provided separate, dedicated summaries specifically focused on the terminology itself. While presenting terminologies within disease contexts may be helpful for certain applications, such as project planning or research, it often required additional time and effort for bedside nurses to scan through results to identify information directly applicable to immediate patient care decisions. A more streamlined and patient-care-focused presentation of nursing terminologies would enhance the usability of these tools in clinical practice.

Transparency

The nursing-specific PoCTs, in general, appeared to lack clearly articulated conflict of interest policies or statements, both within their content and on their product websites. As indicated in Table 2, not all investigators were able to readily locate these materials, suggesting a potential issue with findability and transparency. DynaMed and UpToDate, in contrast, both have publicly accessible conflict of interest policies [15,16] that could serve as examples for nursing PoCT vendors to emulate. It is crucial that nurses who contribute as authors or editors for nursing point of care tools are required to disclose any potential conflicts of interest to maintain the integrity and trustworthiness of the information provided. The investigators were also surprised to find instances where nursing-related content within some platforms may not have been authored or reviewed by nurses. For example, some materials within ClinicalKey Nursing listed authors who were not nurses. This oversight demonstrates a potential lack of recognition for the specialized expertise and practical experience of nurses. It is important to note that not all content entries listed authors, and investigators may not have reviewed identical entries across each PoCT, highlighting a need for further investigation into content authorship and review processes.

Maintaining information currency is paramount in healthcare. The investigators observed inconsistencies in how frequently each PoCT indicated content updates and also disagreed on the ease of identifying when a specific topic had been updated. DynaMed stood out as the only PoCT that provided a dedicated section explicitly detailing updates for each topic. The other platforms that included dates generally did not specify which portions of the content had been recently revised, making it more challenging for users to quickly identify practice-changing updates. The ability to readily identify changes in practice standards without having to meticulously scan lengthy documents is a significant time-saving feature for busy nurses and enhances the usability of point of care tools in dynamic clinical environments.

Customization

The investigators recommend that vendors prioritize the integration of robust customization features into nursing point of care tools. Features such as the ability to add internal notes to procedures and patient education materials, or to save frequently used searches and set up personalized alerts, could significantly streamline workflows and enhance efficiency for nurses. These customization options need to be user-friendly and more widely available, particularly for nurses involved in developing or updating hospital policies and clinical procedures. While all evaluated PoCTs offered mobile apps for both Android and iOS platforms, investigators noted challenges in locating or downloading apps when working remotely. Furthermore, not all apps offered offline access capabilities, which is a critical feature for clinical units with unreliable wireless connectivity. Ensuring offline access and simplifying app acquisition are important considerations for enhancing the utility of mobile PoCT access.

User Perception

While the rubric initially included a section focused on user perception, the investigators, upon discussing the pilot testing results, ultimately decided to remove this section from the final rubric. Their rationale was that, as librarians with specialized expertise in information resources, their perception of usability and user experience might differ significantly from that of the primary target audience – practicing nurses. Furthermore, their familiarity with and training in evaluating diverse types of evidence-based resources could skew their perceptions of ease of use and relevance compared to healthcare professionals in general. To address this recognized gap and gain direct insights into user experience, a subsequent study [17] was conducted to specifically survey nurses’ experiences using PoCTs to answer clinical questions in their daily practice. This separate study aimed to capture the authentic user perspective, complementing the rubric-based evaluation conducted by the librarians.

LIMITATIONS

The primary objective of this project was to develop and pilot test a rubric specifically designed to evaluate nursing point of care tools based on the availability and quality of nursing-focused content. The limitations of both the rubric development process and the pilot testing phase primarily stem from the observed variability in criteria ratings among investigators and the inherent biases of the investigators as health sciences librarians.

The rubric was designed to be as objective as possible, focusing on whether specific criteria could be demonstrably located within a given PoCT. However, during pilot testing, it became evident that the interpretation of certain criteria was more subjective than initially anticipated. Not all investigators consistently located specific content types, potentially due to differing search strategies and approaches to navigating the PoCT interfaces. Regarding the “Coverage of Nursing Topics,” there was some disagreement among investigators about whether the search results retrieved were truly sufficient to answer a typical clinical reference question on the topic. It is reasonable to infer that if experienced investigators encountered difficulties in locating relevant information, average end-users might face similar or greater challenges in their daily practice.

Furthermore, after developing and pilot testing the rubric, the investigators recognized the critical importance of incorporating direct feedback from nurses in the PoCT evaluation process. While librarians possess expertise in assessing the credibility and potential utility of information resources, and in judging whether a resource aligns with the general information needs of end-users, the primary audience – in this case, practicing nurses – is best positioned to determine if a resource is truly user-friendly, relevant to their daily workflow, and worthy of repeated use in clinical practice. Moreover, content experts, such as nurses, are essential for making nuanced judgments about the clinical relevancy and applicability of the information provided within PoCTs to real-world patient care scenarios.

The scope of the study was limited to evaluating only five of the numerous PoCTs currently available in the market. Of these five, two (ClinicalKey Nursing and Lippincott) were only accessible through brief trial subscriptions. The other three PoCTs (NRC+, DynaMed, UpToDate) had been extensively used by the investigators in their professional roles, and this pre-existing familiarity could have inadvertently influenced their scoring within the rubric, introducing potential bias. For the “Customization” section of the rubric, the investigators acknowledge that they should have considered accessibility features as a specific criterion. Given that some PoCTs include patient education materials, future rubric iterations could incorporate an assessment of how readily these materials can be customized or adapted for patients with disabilities, ensuring inclusivity and equitable access to information. Regarding the evaluation of mobile apps, not all investigators were able to download and test the apps remotely, as they were working from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Those who had not previously downloaded the apps were unable to do so due to institutional access restrictions and were thus unable to fully evaluate their functionality. Finally, the rubric itself was not formally tested for validity or reliability in this pilot study. Further research and rigorous psychometric testing are warranted to establish the rubric’s validity and reliability for broader application in PoCT evaluations.

CONCLUSIONS

It is imperative that libraries and hospitals engage in collaborative and data-driven decision-making processes when selecting which nursing point of care tools to license. Decisions should move beyond being solely driven by budgetary constraints or brand recognition. Employing transparent evaluation criteria, grounded in a thorough understanding of the target audience’s information needs, generates more robust and meaningful data to inform the PoCT selection process.

Overall, our evaluation revealed that no single nursing point of care tool definitively outperformed all others, and none comprehensively satisfied all of the rubric criteria. The developed rubric effectively highlighted the unique strengths and weaknesses of each PoCT, providing valuable information to guide the selection process. For institutions supporting a diverse range of practicing nurses, the investigators recommend considering a dual-PoCT strategy: licensing both a dedicated bedside nursing-focused PoCT (such as Nursing Reference Center Plus or Lippincott Advisor and Procedures) and a more broadly focused PoCT that covers advanced diagnostic and treatment information needs (such as DynaMed or UpToDate). The findings of this case report align with existing literature, which suggests that no single PoCT is universally superior and that subscribing to multiple resources is often necessary to adequately meet the diverse information needs of healthcare professionals [1,4,6].

The results from this rubric-based evaluation, along with findings from a separate survey [17] assessing nurses’ perceptions of using some of the evaluated PoCTs, were shared with nursing leadership at the University of Illinois Chicago. Interestingly, nursing leadership, after reviewing the comprehensive data, did not feel that the findings supported continuing the subscription to NRC+. Ultimately, they selected Lippincott Nursing Products as their preferred nursing PoCT solution. The library subsequently canceled its subscription to NRC+ on July 1, 2021, and Lippincott Nursing Products was rolled out to the hospital’s nursing staff beginning in December 2021, demonstrating the real-world impact of a systematic and evidence-based approach to PoCT evaluation and selection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the Advanced Practice and Research Council at the University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System for their invaluable feedback and contributions to the development of the evaluation rubric. We also acknowledge and thank the sales representatives from Elsevier and Lippincott for arranging trial access and product demonstrations, which were essential for conducting this evaluation. Finally, we express our appreciation to Professors Deborah Lauseng, Regional Head Librarian, Peoria; Glenda Insua, Reference and Liaison Librarian; and Rosie Hanneke, Head Librarian, Information Services & Research, for their expert assistance with the review and revision of this manuscript, enhancing its clarity and scholarly rigor.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data associated with this article are available in Appendix B. The data will be made available on the authors’ institutional repository upon publication to ensure transparency and facilitate further research in this area.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Annie Nickum: Conceptualized and designed the study; conducted the literature review; drafted the original manuscript, and contributed to reviewing and editing; performed formal data analysis. Emily Johnson-Barlow: Conceptualized and designed the study; conducted the literature review; drafted the original manuscript, and contributed to reviewing and editing; performed formal data analysis; created data visualizations. Rebecca Raszewski: Conceptualized and designed the study, conducted the literature review; contributed to the original draft, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. Ryan Rafferty: Contributed to drafting the original manuscript, and reviewing and editing; created data visualizations; managed resource acquisition.

SUPPLEMENTAL FILES

Appendix A: Rubric Instrument (122.9KB, pdf)

Appendix B: Research Results (102KB, pdf)

REFERENCES

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A: Rubric Instrument (122.9KB, pdf)

Appendix B: Research Results (102KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with this article are available in Appendix B. The data will be made available on the authors’ institutional repository upon publication.

[#R1]: Green ML, Ruffolo ML, N நிரூபிக்கும் ML. Point-of-care clinical applications: the evidence for librarian involvement. Med Ref Serv Q. 2006 Winter;25(4):1-14. [DOI: 10.1300/J115v25n04_01] [PMID: 17182415]

[#R2]: Thornton JD, Lee CS. Information needs of nurses in non-acute care settings: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs. 2011 May;67(5):931-41. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05581.x] [PMID: 21143505]

[#R3]: Booth A. Bridging the research-practice gap? The role of evidence-based information resources for nurses. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2008;5(4):193-5. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00137.x] [PMID: 18983519]

[#R4]: Marshall JG. The evaluation of library services: a literature review. Libr Trends. 1988 Winter;36(3):537-57. [PMID: 10289988]

[#R5]: Cooper ID, Crum JA. New activities and changing roles of health sciences librarians: a systematic review, 1990-2000. J Med Libr Assoc. 2003 Jul;91(3):288-99. [PMID: 12883621]

[#R6]: Weightman AL, Williamson J. Evidence-based librarianship: incorporating evidence into practice. Health Info Libr J. 2005 Mar;22(2):71-9. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2005.00564.x] [PMID: 15953408]

[#R7]: Hallikainen J, Hyppönen H, Saranto K. Evidence-based information retrieval in healthcare: a systematic review of information retrieval tools. Health Info Libr J. 2012 Jun;29(2):75-93. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2012.00977.x] [PMID: 22720751]

[#R13]: Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing, at the Institute of Medicine. The future of nursing: leading change, advancing health. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011.

[#R14]: American Nurses Association. Nursing: scope and standards of practice. 3rd ed. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association; 2015.

[#R15]: DynaMed [Internet]. Ipswich (MA): EBSCO Information Services. Conflict of interest policy. [cited 2022 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.dynamed.com/about/editorial-policies#ConflictOfInterest

[#R16]: UpToDate [Internet]. Waltham, MA: UpToDate. Conflict of interest policy. [cited 2022 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate/about/editorial-policy

[#R17]: Nickum A, Barlow EJ, Raszewski R, Rafferty R. Nurses’ perceptions of point-of-care tools in answering clinical questions. [unpublished manuscript].