INTRODUCTION

The increasing complexity of healthcare services and fragmented care pathways are significant contributors to adverse health outcomes and diminished patient experiences.[1-4] In response to these challenges, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) has launched numerous demonstration projects. These initiatives are designed to evaluate novel payment models that incentivize the integration of services across the entire continuum of care.[5, 6] Over the past two decades, care coordination interventions have garnered substantial attention as a strategy to mitigate fragmentation, particularly with the aim of reducing the utilization of acute care services such as hospital admissions and emergency department (ED) visits.[7, 8]

Care coordination models typically employ systematic strategies to enhance continuity and facilitate seamless transitions of care.[7, 9, 10] These models often manifest as care or case management, where a designated individual or team assists patients in navigating their medical care and interactions within healthcare systems. These interventions are frequently targeted at populations identified as being at elevated risk for acute care utilization, based on a variety of risk criteria.[7, 8] Despite the extensive study of diverse care coordination models across various settings, questions remain about their capacity to effectively address care gaps and improve patient outcomes. Furthermore, for healthcare providers considering the implementation of such models, a clearer understanding of the evidence supporting the tools and approaches used to facilitate and monitor implementation is crucial.

To support ongoing efforts aimed at standardizing and integrating care coordination services within Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities,[11] the VA Evidence Synthesis Program (ESP) commissioned a review of the evidence concerning the implementation and outcomes of care coordination models for community-dwelling adults at high risk of acute care use.[12] This comprehensive evidence report was structured in multiple stages and included a systematic review of reviews,[13] an analysis of primary research studies included in the eligible reviews, and interviews with key informants. Initially, we present qualitative summaries of findings from eligible systematic reviews, focusing on the essential characteristics and effectiveness of care coordination interventions. Subsequently, we detail the results derived from primary research studies of effective interventions—defined as those demonstrating a reduction in hospitalizations and/or ED visits—regarding settings, and the tools and approaches utilized to evaluate patient trust, care team integration, and enhance patient-provider communication. Finally, we incorporate insights from key informant interviews to address remaining gaps in the published literature, particularly in relation to the tools and approaches employed across various interventions. We also discuss limitations within the current evidence base and propose recommendations for future research and policy development in the realm of Interdisciplinary Critical Care Management Models And Tools.

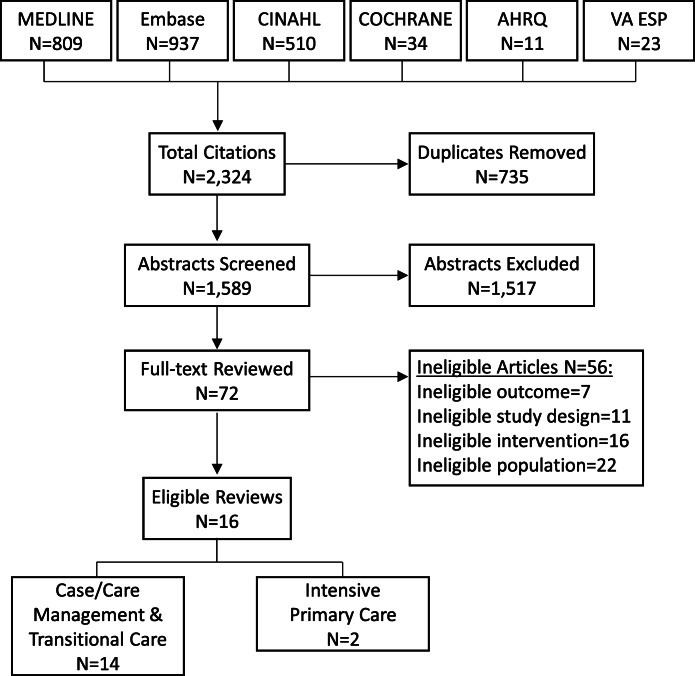

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Search and selection process for systematic reviews examining interdisciplinary critical care management models.

METHODS

Conceptual Model and Scope

In collaboration with our stakeholders from the VA Offices of Nursing Services, and Care Management and Social Work, and with guidance from an expert advisory panel, we adopted the Framework for Care Coordination in Chronic and Complex Disease Management[10] (Table 1) to structure our scope refinement and protocol development. We explored various resources and existing models for care coordination, including the AHRQ Care Coordination Atlas[7] and the Integrated Team Effectiveness Model[14]. We selected this framework for its detailed delineation of specific, potentially measurable concepts within broader domains, which closely align with the classic structure-process-outcome model for healthcare quality.[15] Crucially, this framework distinguished between relevant concepts within and between healthcare teams, an aspect our stakeholders identified as critical for VHA programs, particularly concerning communication and mechanisms between teams.

We further refined the chosen framework by: (1) specifying that team roles within coordination mechanisms include identifying who contacts patients and the methods of contact; and (2) reorganizing outcomes into categories relevant to patients (e.g., patient experience, quality of life, and survival), healthcare teams (e.g., job satisfaction and burnout), and health systems (e.g., acute care utilization) (Table 1). While healthcare utilization can be measured at the patient level, we considered these outcomes to be primarily oriented towards health system priorities rather than patient-centered outcomes.

Table 1. Adapted Framework for Interdisciplinary Care Coordination in Chronic and Complex Disease Management

| Context and Setting | Coordination Mechanisms | Emergent Integrating Conditions | Coordinating Actions | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within teams | • Team composition • Experience and history • Power distribution • Resources | • Plans, rules, and tools • Objects, representations, artifacts, and information systems • Roles (e.g., who contacts patients and how) • Routines • Proximity | • Accountability • Predictability • Common understanding • Trust | • Situation monitoring • Communication • Back-up behavior |

| Between teams | • Multiteam system composition • Linkages between teams • Alignment of organizational cultures/ climates • Governance and payment structure | • Boundary spanning • Information exchange • Collective problem-solving and decision-making • Negotiation • Mutual adjustment |

Adapted from Weaver et al. (2018)[10] Framework for Care Coordination.

Applying this framework, and in alignment with stakeholder priorities, we defined effective interventions as those that achieved a reduction in hospitalizations and/or ED visits. We sought to gather information on the essential characteristics of effective interventions, particularly focusing on elements within the Context and Setting, and Coordinating Mechanisms domains. Examples of these characteristics include the use of multidisciplinary teams versus primarily single case manager models, and the incorporation of home visits as opposed to solely telephone contacts or outpatient visits. We also searched for evidence on the tools and approaches utilized to assess Emergent Integrating Conditions (e.g., trust within teams) and Coordinating Actions (e.g., within-team communication). Our stakeholders emphasized that these tools were vital for monitoring the implementation progress of VHA programs, even before other outcomes could be evaluated. Finally, to enhance the applicability of our findings, we aimed to understand the characteristics of healthcare systems and communities where effective interventions had been successfully implemented.

Key Questions (KQ)

For community-dwelling adults with various ambulatory care sensitive conditions and/or at increased risk of recurrent hospitalization or ED visits:

- KQ1: What are the key characteristics of interdisciplinary care coordination models (of varying types) designed to reduce hospitalization or ED visits?

- KQ2: What is the impact of implementing these care coordination models on hospitalizations, ED visits, and patient experience (e.g., Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems)?

- KQ3: What are the setting characteristics in which effective interdisciplinary models have been implemented?

- KQ4: Among effective models, what approaches and tools have been employed to:

- Measure patient trust or working alliance?

- Assess team integration?

- Enhance communication between patients and providers?

Search Strategy

Our initial focus was on identifying systematic reviews that evaluated a range of care coordination models. We searched for English-language systematic reviews published from inception up to September 2019 in MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, AHRQ Evidence-based Practice Center, and VA ESP reports. Search terms included MeSH terms and free text related to care coordination interventions (e.g., care or case management, interdisciplinary care, and intensive primary care) and systematic reviews (Appendix 1 in the supplementary material).

Based on our prior experience with published evidence on care coordination and the information typically reported in systematic reviews, we anticipated that eligible reviews might not provide sufficient detail, especially concerning setting characteristics and the tools and approaches used (KQ 3 and 4). Therefore, we proactively planned to undertake the following additional steps: (1) examination of primary research studies included in eligible reviews; (2) an updated search for relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of care coordination interventions in MEDLINE and Embase, covering the period from the most recent eligible review to February 2020 (Appendix 1 in the supplementary material); and (3) key informant interviews with team members who implemented interventions described in primary research studies (see details below).

Screening and Selection

Using predefined criteria (Appendix 2 in the supplementary material), systematic review search results were evaluated, and exclusions were made based on consensus between two reviewers. Eligible populations included community-dwelling adults with a spectrum of ambulatory care sensitive conditions (as defined by AHRQ quality metrics), such as heart failure and chronic lung disease[16], and/or those at higher risk for acute care episodes (as defined by review and primary study authors). Reviews focusing exclusively on a single health condition were excluded. Eligible interventions encompassed diverse models, including care or case management and home-based primary care. Eligible reviews were required to include hospitalizations and/or ED visits as outcomes of interest in their objectives or results. During full-text review, two individuals independently assessed eligibility, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

From each eligible review, we also identified all included primary studies. Two reviewers assessed these primary studies for relevance to KQ 3–4. As noted, studies relevant to KQ 3 were those reporting effective care coordination models that reduced acute care visits. Models that only demonstrated improvements in patient experience were not considered applicable to KQ 3. In addition to the above criteria, we also applied the following: studies conducted in the USA, and RCTs or quasi-experimental observational studies (e.g., comparative control cohort or interrupted time series).[17] We followed a similar screening and review process for results from the supplementary search for RCTs published between 2018 and February 2020.

Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

We assessed the quality of included systematic reviews using criteria adapted from AMSTAR 2,[18] categorizing the overall quality as high, medium, or low (Appendix 3 in the supplementary material). We also noted whether review authors assessed for small study effects and reporting outcome biases. From all eligible reviews, we abstracted the following: target populations (e.g., frequent ED utilizers or individuals with complex chronic conditions); search query dates; and the number and characteristics of included primary research studies (location, setting, and study design). From high- and medium-quality reviews, we planned to abstract detailed information on: characteristics of care coordination models; pooled effects or qualitative summaries of results on hospitalizations, ED visits, and/or patient experience; setting characteristics; and tools and approaches used to measure patient trust or working alliance, assess healthcare team integration, and/or improve patient-provider communication.

From relevant primary studies reporting successful reductions in hospitalizations and/or ED visits, we abstracted: effects on main outcomes; participant, intervention, and setting characteristics; and relevant tools and approaches. We also examined related articles referenced by primary studies for additional intervention details.

Data Synthesis

Given the heterogeneity of eligible reviews and studies, we employed a qualitative synthesis approach, focusing on the key characteristics and effectiveness of interdisciplinary care coordination models. Where reported, we noted the strength of evidence assessments made by review authors. For primary studies reporting effective interventions, we summarized setting and intervention characteristics, effects on primary outcomes, and tools and approaches used.

Key Informant Interviews

We conducted semi-structured interviews with researchers and team members involved in implementing care coordination models, as described in relevant primary studies, regardless of intervention effectiveness. We invited 25 individuals and completed interviews with 11 participants.

The primary aim of these interviews was to address gaps in the published studies regarding intervention tools and approaches (KQ4). We also included questions about intervention uptake and sustainability. A general version of the interview guide is available in Appendix 4 in the supplementary material; individual guides were customized using published and online information. Interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes and were audio-recorded. We reviewed contemporaneous notes and audio recordings to develop summaries for each intervention. Subsequently, we analyzed all interview summaries to identify key themes across major topics relevant to interdisciplinary critical care management models and tools.

RESULTS

Overview of Eligible Systematic Reviews

We screened 2,324 unique citations, reviewed 72 full texts, and identified 16 eligible systematic reviews (Figure 1). Fourteen of these reviews examined case management or transitional care interventions,[19-32] while 2 evaluated intensive primary care models, such as home-based primary care[33, 34]. All reviews encompassed a variety of models within these broad categories. Four reviews included only RCTs,[19, 25, 26, 31] whereas others also included observational studies. Most reviews included studies from multiple countries, but 3 were limited to US-based studies.[20, 24, 28] Seven reviews focused on patients at higher risk for acute care utilization (i.e., high utilizers),[19, 22-24, 27, 28, 30] and one examined interventions for frail adults.[31] Six reviews were rated as high quality,[23, 26, 27, 29, 30, 34] 6 as medium quality,[19, 22, 24, 25, 31, 33] and 4 as low quality[20, 21, 28, 32] (Appendix 3 in the supplementary material). Overall, 8 reviews (7 high and medium quality) evaluated selective outcomes reporting bias; of the 3 reviews that conducted quantitative meta-analyses, 2 used funnel plots to assess for publication bias (Appendix 3 in the supplementary material). Our detailed results primarily focus on high- and medium-quality reviews, as presented below and in Appendix 5 in the supplementary material.

Primary research studies included in all eligible reviews were assessed for relevance (see METHODS). From 272 unique primary studies, we identified 16 RCTs[35-50] and 9 observational studies[51-59] that evaluated relevant interventions conducted in the USA. Most studies were included in 1–2 eligible reviews, but 7 studies[36, 38, 42, 48, 52, 57] were included in 3 or more reviews (Appendix 6 in the supplementary material). The updated search for RCTs (published in 2018 or later) identified 1,048 unique citations. We reviewed 21 full texts and found 2 additional relevant RCTs; both reported interventions that were not effective in reducing hospitalizations and/or ED visits.[60, 61] Overall, 20% of relevant RCTs (4 of 20)[38, 43, 46, 49] showed reductions in hospitalizations and/or ED visits. In contrast, 78% of relevant observational studies (7 of 9)[51-55, 57, 58] reported effectiveness for these outcomes.

KQ1: Key Characteristics of Interdisciplinary Care Coordination Models

All reviews summarized various components of the interventions, noting variations in team composition and intervention elements (e.g., multidisciplinary care plans). Patient communication primarily occurred in person (clinical or home settings) or via telephone. Four reviews specifically addressed key characteristics of care coordination models,[23, 29, 31, 34] all including primary studies conducted both in and outside the USA (e.g., Canada, European countries, and Australia). Among these, Hudon et al.[23] used qualitative comparative analysis to examine characteristics of effective case management models, finding that careful participant selection was necessary but not sufficient. Additional essential elements included high intensity (defined by caseload, frequency, and types of patient contacts) or a multidisciplinary care plan. Smith et al.[29] also conducted a qualitative synthesis, reporting that interventions targeting specific risk factors were more likely to be effective. Conversely, Van der Elst et al.[31] conducted quantitative subgroup analyses by intervention duration and different approaches to address frailty, finding no significant differences in effect. Lastly, Totten et al.[34] examined home-based primary care interventions and, through qualitative synthesis, found no specific pattern of components consistently associated with effectiveness. Additionally, 2 reviews[19, 33] attempted to identify key components but were unable to draw definitive conclusions, citing challenges such as a lack of published information describing components and implementation fidelity.

KQ2: Impact of Implementing Interdisciplinary Care Coordination Models

The effects of care coordination interventions on hospitalizations, ED visits, and patient experience are summarized in Figure 2 and detailed in Appendix 5 in the supplementary material. Of 12 high- and medium-quality reviews, most used qualitative synthesis, and the majority reported unclear or mixed effects across the different outcomes (Figure 2).

Summary of findings from high- and medium-quality systematic reviews on the effects of interdisciplinary care coordination interventions.

Case Management and Transitional Care Interventions

Among 10 reviews focusing on case management or transitional care interventions, 6 assessed effectiveness in reducing hospitalizations, with 4 reporting mixed or unclear results[19, 23, 25, 26] and 2 finding no effectiveness[29, 31] (Figure 2 and Appendix 5 in the supplementary material). The populations studied in these reviews included high utilizers,[19, 23] individuals with chronic disease or multimorbidity,[25, 26, 29] and frail older adults.[31] Le Berre et al.[26] evaluated transitional care interventions using quantitative meta-analyses. Incorporating data from 11 to 35 RCTs across various follow-up periods, they found no effect at 1 month (risk difference [RD] −0.03 [−0.05, 0]) but some reduction at 3–18 months (RD range −0.05 to −0.11) (Appendix 5 in the supplementary material). Van der Elst et al.[31] conducted quantitative meta-analyses to evaluate diverse case management interventions for frail community-dwelling older adults; pooled results from 5 RCTs showed no reduction in hospitalizations (odds ratio [OR] 1.13, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.95, 1.35) (Appendix 5 in the supplementary material).

Seven reviews examined effects on ED visits, with only 2 indicating that care coordination reduced ED visits.[25, 27] Joo et al.[25] focused on adults with chronic disease and identified 6 studies showing reductions in ED visits. Moe et al.[27] addressed results for high utilizers and reported a median rate ratio (care coordination vs. control) of 0.63, with an interquartile range of 0.41–0.71. Le Berre et al.[26] also examined care coordination for high utilizers and reported pooled meta-analyses showing a reduction at 3 months (RD −0.08 [−0.15, −0.01]) but no significant differences at 1, 6, and 12 months. The remaining 4 reviews[22-24, 30] evaluated results for high utilizers, used qualitative synthesis, and reported unclear or mixed effects on ED visits (Figure 2 and Appendix 5 in the supplementary material).

One review specifically addressed effects on patient experience and, using qualitative synthesis, found inconsistent results.[23]

Intensive Primary Care Interventions

Two reviews evaluated intensive primary care interventions, both using qualitative synthesis. Totten et al.[34] focused on home-based primary care for adults with chronic illness and/or disabilities, reporting reduced hospitalizations (moderate strength of evidence) and ED visits (low strength of evidence), as well as improved patient and caregiver satisfaction (low strength of evidence) (Figure 2 and Appendix 5 in the supplementary material). In contrast, Edwards et al.[33] examined several different models of intensive primary care for those at high risk of hospital admission and/or death, finding inconsistent results across studies.

KQ3: Setting Characteristics of Effective Interdisciplinary Models

Few reviews provided details on specific setting characteristics beyond the countries where studies were conducted. Soril et al.[30] examined case management models and reported that 15 of 16 included studies were single-site, typically in urban settings. Totten et al.[34] attempted to address organizational settings for home-based primary care but found insufficient published information.

To gain a better understanding of setting characteristics, we examined 11 relevant primary studies that reported effective interventions in the USA. We categorized these interventions as transitional care (n=5),[37, 43, 51, 53, 54] outpatient care or case management (nurse or social worker led) (n=4),[46, 48, 57, 58] or other intensive primary care models (n=2)[52, 55] (Table 2). Settings varied, including rural community hospitals, urban academic medical centers, and public hospitals serving predominantly low-income and uninsured populations. Detailed intervention characteristics and effects are also presented in Table 2. No clear correlation was evident between setting differences, intervention types, and patient populations.

Table 2. Primary Research Studies: Characteristics, Settings, and Results of Effective Interdisciplinary Care Coordination Models

| Author, year; study design*; N(I,C)** | Intervention name; eligibility criteria | Setting characteristics | Description of patient contacts | Intervention effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalizations | ||||

| Transitional care interventions | ||||

| Capp, 2017[51] Cohort; I=406 C=3396 | Bridges to care; adults with ≥ 2 ED visits and/or hospitalizations in past 180 days | Large urban academic medical center, Colorado | Initial home visit by community health worker within 24–72 h, second visit by PCP within 1 week of ED or hospital discharge; 8 visits over 60 days (community health worker, nurse, primary care provider, and/or behavioral health provider) depending on patient needs. | Average no. of admissions per person, 180 days before enrollment: I=1.04, C=1.15 180 days after 60-day intervention: I=0.75, C=1.02 Difference of differences = −0.16, P < 0.05 |

| Hamar, 2016[54] Cohort; I=560 C=3340 | Care transition solution; adults admitted with ≥ 1 condition (COPD, heart failure, myocardial infarction, pneumonia) | 14 community hospitals in north Texas | Initial visit in hospital with nurse before discharge, then 4 calls over 4 weeks | Proportion with ≥ 1 readmission at 30 days: AOR=0.56 (0.41–0.77) At 6 months: AOR=0.47 (0.35–0.65) |

| Gardner, 2014[53] Cohort; I=21 C=21 | Care transitions intervention; adults participating in Medicare fee-for-service, admitted to hospital | 6 community hospitals, Rhode Island | Initial visit in hospital by nurse, home visit “shortly after discharge,” 2–3 phone calls during 30-day post-discharge period | Propensity score–matched no. of readmissions at 6 months: I=0.65, C=0.93 P=0.01 |

| Coleman, 2006[38] RCT; I=379 C=371 | Care transitions intervention; older adults (≥65) admitted with ≥ 1 condition (stroke, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, etc.) | Community health system, Colorado | Nurse met patients in hospital before discharge, home visit within 48–72 h of discharge, then 3 more times during the 28-day post-discharge period. | Proportion with ≥ 1 readmission at 30 days: I=0.08, C=0.12 (AOR 0.59 [0.35, 1.00], P=0.048) At 90 days: I=0.17, C=0.23 (AOR 0.64 [0.42, 0.99], P=0.04) At 180 days: I=0.26, C=0.31 (AOR 0.80 [0.54, 1.19], P=0.28) |

| Naylor, 1999[43] RCT; I=177 C=186 | Transitional care model; older adults (≥65) admitted with ≥ 1 condition (heart failure, respiratory infection, orthopedic procedure, etc.) | 2 urban hospitals affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania | Initial nurse visit within 48 h of admission, visits at least every 48 h during admission, home visits after discharge (first within 48 h, second 7–10 days post-discharge, additional visits based on patients’ needs), weekly nurse-initiated phone contact | Proportion with ≥ 1 readmission at 24 weeks: I=0.20, C=0.37 P < 0.001 |

| Outpatient care or case management | ||||

| Shah, 2011[57] Cohort; I=98 C=160 | Care management program; adults aged 18–64, met “frequent user criteria” | Public safety-net hospital and clinics in Kern County, CA | Care managers (social worker or medical office assistant) met with patients at least monthly in the home and/or clinic, for variable lengths of time (care manager decided when patient graduated program) | Adjusted ratio of no. of admissions per year (I:C) was 0.81, P=0.38 |

| Peikes, 2009[46] RCT; Mercy Medical Center (1 of 15 sites) I=669, C=467 | Medicare coordinated care demonstration; adults participating in Medicare fee-for-service and with ≥ 1 condition (heart failure, COPD, etc.) | Mercy Medical Center—rural community hospital, Iowa | Nurse completed in-person evaluation within 2 weeks of enrollment, contacted patient at least monthly, 69% were in-person (either at home or during clinic visit) | Average no. of admissions per person per year: I= 1.15, C=0.98 P=0.02 |

| Shumway, 2008[48] RCT; I=167, C=85 | Comprehensive case management; adults with ≥ 5 ED visits in past 12 months and had “psychosocial problems that could be addressed with case management” | Urban public hospital in San Francisco, CA | Social workers completed assessments, individual and group supportive therapy, assistance to a variety of community resources, and “assertive community outreach” (frequency and schedule of patient contacts NR) | Effect size NR, P=0.08 for treatment effect in adjusted model for visits over 2 years |

| Sommers, 2000[58] Cohort I=280 C=263 | Senior care connections; adults ≥65 with difficulty in ≥1 instrumental activity of daily living and ≥ 2 chronic conditions | Primary care clinics in San Francisco Bay area, CA | Initial home visit with case manager (nurse or social worker), treatment plan drafted by care team (nurse, social worker, primary care provider), patients contacts via phone, home visits, small group sessions, or office/hospital visits at least once every 6 weeks | Number of admissions per person per year at baseline: I=0.35, C=0.06 during year 1: I=0.38, C= 0.34 during year 2: I=0.36, C=0.52 P=0.03 |

| Other intensive primary care models | ||||

| Crane, 2012[52] Cohort; I=34 C=36 | Drop-in group medical appointments; uninsured, family income ≤ 200% federal poverty level, ≥ 6 ED visits in past year | Rural community hospital, North Carolina | Twice weekly groups sessions, short individual visit right after; direct phone access to nurse care manager; team included nurse, primary care, and behavioral health providers | NR |

| Meret-Hanke, 2011[55] Cohort; I=3889 C=3103 | Program for all-inclusive care for the elderly; adults >65, with functional limitations or dementia, low income | National US program | Interdisciplinary care teams provided care management, clinical monitoring, and updated care plan in response to changes in enrollee’s health and functional status | Propensity score-matched any hospitalization at 6 months: AOR 0.35, P < 0.001 At 2 years: AOR 0.16, P < 0.001 |

Primary studies on effective interdisciplinary critical care management models and tools.

KQ4: Tools and Approaches Used by Effective Models

No systematic review commented on the specific tools and approaches used to measure patient trust or care team integration, or to improve patient-provider communication within interdisciplinary critical care management models. Among the relevant primary studies, 5 described various approaches to enhance patient-provider communications, including patient coaching, creating lists of key concerns, and role-playing.[38, 46, 53, 57, 62] In two studies, care coordinators also attended outpatient visits with patients and their providers.[46, 57] No study detailed specific measures used to assess patient trust or care team integration. We identified a companion article for one study[38] that reported results from qualitative interviews evaluating patient experiences and their relationship with care coordinators.[45]

Key Informant Interviews

Key insights from our interviews and supporting quotes are summarized in Table 3. We did not identify any additional tools or approaches for assessing patient trust or care team integration, or for improving patient-provider communications beyond what was reported in the literature. Supplementary materials provided by interviewees indicated that patient experience assessments sometimes included elements conceptually related to patient trust, such as the perception that the care coordinator was knowledgeable and understood patient needs.

Table 3. Summary of Key Takeaways from Key Informant Interviews on Interdisciplinary Critical Care Management

| What Worked Well |

|---|

| 1. Multidisciplinary Collaboration • Strong relationships and communication with providers across primary care, specialty care, and various disciplines (e.g., social work). “Patients had issues that crossed medical, behavioral, and social domains, so it was critical to have experts in these areas on the team.” • Diverse collaboration methods including outreach calls, email, and in-person meetings. 2. Dedicated Staff for Intervention • Crucial for ensuring care continuity, timely management adjustments, and building trust with patients and families. “It made a difference that [there was a] dedicated person to respond to alerts, contact physicians to facilitate interactions, etc.) …[C]are suggestions…were quickly implemented.” “The fact that we had the same nurse following the patient…was viewed by patients and family caregivers as really central…” 3. Knowledge of and Relationship with Community-Based Services • Leveraging services such as transportation, food banks, home-delivered meals, and substance abuse treatment. “Establishing a vast network of relationships [with community organizations] was important … to effectively help patients.” 4. Essential Staff Qualities and Skills • Dedication, compassion, strong communication, and relationship-building abilities were paramount. |

| Challenges and Sustainability |

| 1. Difficulty Impacting Readmissions • Short timeframe for metrics, and numerous complex factors to address. “30 days doesn’t give you sufficient time…especially in elderly patients with many issues… Everything that could be possibly going wrong is going wrong…” 2. Adaptation of Interventions • Interventions modified over time to align with evolving priorities (e.g., adapting for different high-risk populations). • Selective adoption of components or techniques across different implementation sites. 3. Stakeholder Engagement and Financial Viability • Senior leadership engagement as key to long-term sustainability. “[P]artnership between the architects of these models and the health systems, …strong collaboration…is required to meaningfully move evidence into health systems…” • Challenges in determining which entity within the health system benefits most and should bear financial responsibility for staffing and other resources. |

Overall, several elements were consistently identified as contributing to the success of interdisciplinary critical care management models: multidisciplinary collaboration, dedicated intervention staff, strong community service relationships, and key staff qualities. However, the sustainability of interventions varied, with some ceasing after research study completion. Challenges faced and sometimes overcome included meeting short-term readmission metrics, adapting to changing health system priorities, and securing buy-in and financial ownership from key stakeholders.

For future interventions, some interviewees suggested focusing on patients with less severe conditions and/or modifiable risk factors, acknowledging the challenge that this approach might require serving a larger patient volume to achieve significant reductions in acute care utilization at a population level. As one interviewee noted, “You can allocate a lot of resources to extremely high need patients…or you can allocate resources to a larger population and … have a smaller impact on individual level, but on population level have greater impact…”

DISCUSSION

This comprehensive evidence review, supplemented by key informant interviews, evaluated interdisciplinary care coordination interventions. The complexity and heterogeneity of these interventions, varying across multiple dimensions, presented significant challenges for evidence comparison and synthesis. Most reviews reported mixed or inconclusive effects on reducing hospitalizations or ED visits. However, two reviews identified key characteristics of effective models, emphasizing the importance of targeted selection criteria based on clear risk factors and patient needs. One of these reviews further highlighted the necessity of high-intensity models—characterized by lower caseloads and more frequent patient contacts—or the implementation of multidisciplinary care plans.

Among the 11 primary studies demonstrating effective interventions, none reported specific tools or approaches for measuring patient trust or healthcare team integration, which are critical components of interdisciplinary critical care management models and tools. Approaches to improve patient-provider communication included coaching and role-playing. In some interventions, care coordinators facilitated direct communication with providers on behalf of patients, including attending clinical appointments. Key informants highlighted substantial challenges in implementing and sustaining these interventions, including difficulties in meeting short-term readmission metrics, adapting to evolving health system priorities, and ensuring stakeholder engagement.

Among the systemic factors contributing to healthcare fragmentation in the US, complex payment policies and a regulatory environment that impedes service integration are paramount.[63, 64] These factors create financial disincentives for healthcare organizations to invest in programs aimed at long-term health improvements. Existing barriers also limit the potential impact of interdisciplinary care coordination interventions, which must operate within a system that often perpetuates care gaps and misaligned incentives among providers. CMMI demonstration projects are currently testing innovative payment models to incentivize healthcare delivery restructuring, including bundled payments to promote care integration across settings for specific conditions,[5] and the establishment of patient-centered medical homes in outpatient care.[6] The outcomes of these demonstrations may inform longer-term policy changes that support greater integration of US healthcare services and the broader adoption of effective interdisciplinary critical care management models and tools.

Evidence Gaps and Future Research

Primary research studies employing observational designs were more likely to report reductions in hospitalizations and/or ED visits. However, observational studies are inherently susceptible to residual confounding, selective outcome reporting, publication bias, and false-positive results due to regression to the mean, especially in pre-post cohort designs. Furthermore, evidence for intensive primary care models remains limited; the two eligible reviews on these models included only 4 relevant primary studies.[40, 50, 55, 56]

Notably, studies lacked reports on standardized tools used to assess patient trust or care team integration, essential elements for effective interdisciplinary collaboration. Key informant interviews indicated that some patient experience assessments touched on concepts related to patient trust, but no measures of care team integration were identified. This gap in knowledge regarding reliable assessment tools for patient-coordinator and health team relationships may reflect the prevalent focus on acute care utilization outcomes in care coordination studies, potentially overshadowing the importance of verifying successful implementation through improvements in communication and relationships. The absence of standardized, validated tools to assess these critical aspects hinders the evaluation of existing services and the implementation of new interdisciplinary programs.

Finally, multiple reviews identified a lack of detailed information on intervention implementation and fidelity. To enhance the evaluation and interpretation of effectiveness, future studies should consider adopting frameworks and designs that address implementation outcomes, such as hybrid effectiveness-implementation designs, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), and the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework.[65-68] Studies should clearly define the “core” set of key components of interdisciplinary critical care management models and the “adaptable periphery” of elements that can be tailored to local contexts.[66]

Therefore, we recommend the following actions to advance the field of interdisciplinary critical care management models and tools:

- Employ randomized designs in future evaluations of care coordination interventions to establish causality more rigorously.

- Develop and implement standardized tools to assess patient trust or working alliance, healthcare team integration, and the quality of communication between patients and providers.

- Incorporate study designs that explicitly evaluate implementation outcomes in future research on care coordination models.

- Clearly define “core” intervention components and thoroughly describe local adaptations, particularly in multisite studies, to understand the generalizability and adaptability of interdisciplinary critical care management models and tools.

Implications for Policy and Practice

The current evidence base leaves uncertainty regarding which specific care coordination models should be implemented and how adaptations might enhance their effectiveness and sustainability. Ongoing VHA initiatives have piloted new tools for patient needs assessment and matching patients to appropriate levels of care coordination services.[11] Evaluating the feasibility of broader implementation and its downstream effects on service delivery and patient outcomes is crucial. Furthermore, understanding the differences in utility across diverse settings—large versus small medical centers and clinics, and urban versus rural locations—is essential. These evaluations can also provide valuable insights for non-VHA health systems seeking better tools to align services with patient needs. Given the importance of local adaptations for uptake and sustainability, developing resources and guidance to support these adaptations is valuable. Such guidance must be informed by further research to understand the rationale and impacts of various adaptations in different settings.

As previously noted, substantial policy changes to better align incentives and remove regulatory barriers are likely necessary to significantly reduce healthcare fragmentation in the US. Our findings suggest that effective interventions often require high intensity and multidisciplinary approaches, which may incur higher costs and face greater regulatory challenges in the current healthcare environment. Therefore, sustained, large-scale investments in implementing such models and achieving improved patient outcomes may not be feasible without significant policy reforms.

Finally, it is important to recognize that specific patient populations may require care models that extend beyond standard care coordination services. For example, the VHA has implemented collaborative models such as collocated primary care and mental health services to improve access to mental healthcare.[69] Another effective collaborative model involves the longitudinal integration of oncology and palliative care for cancer patients.[70] These models effectively address specific, prevalent needs within their target populations and provide clearly effective treatments, suggesting that tailored interdisciplinary approaches are essential components of comprehensive critical care management.

Limitations

To align with VA stakeholder priorities, our review focused on interventions effective in reducing hospitalizations and/or ED visits, potentially excluding relevant studies that prioritized other outcomes, such as patient experience. While we acknowledge the importance of patient experience, our stakeholders and key informant interviews emphasized that reducing acute care utilization is often a primary concern for health system leadership and a critical factor for program sustainability. To ensure relevance to the US healthcare context, we limited our primary study inclusion to those conducted in the USA. Our interview participation rate was less than half of those invited, potentially missing unpublished insights on tools and approaches. Lastly, our reliance on effectiveness and strength of evidence determinations from high- and medium-quality systematic reviews means that any methodological limitations within those reviews could affect the validity of our conclusions.

CONCLUSIONS

The existing evidence on care coordination interventions indicates inconsistent effects on reducing hospitalizations and/or ED visits for high-risk community-dwelling adults. It remains unclear whether these interventions should be widely implemented and how they can be best adapted to diverse healthcare settings. Future implementation of new care coordination models should be rigorously evaluated using randomized designs. Policymakers should also consider whether a broader redesign of healthcare services is necessary to fundamentally improve continuity and interdisciplinary collaboration for vulnerable patient populations, moving towards more integrated interdisciplinary critical care management models and tools.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1 (145.7KB, docx) (DOCX 145 kb)

Funding

This work was supported by VA Health Services Research & Development funding for ESP (VA-ESP Project No. 09-009; 2020). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit article for publication.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[References from the original article are listed here]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ESM 1 (145.7KB, docx) (DOCX 145 kb)