Introduction

The significance of the built environment in healthcare settings, particularly in nursing homes and facilities providing high care for vulnerable populations, is increasingly recognized. Systematic assessment instruments play a crucial role in objectively evaluating these environments, moving beyond subjective observations from planners and healthcare professionals. These tools are vital for ensuring consistent and improved care environments, contributing to enhanced patient well-being and safety.

Many established and rigorously validated assessment tools are originally published in English. To effectively utilize these resources globally, especially in diverse cultural contexts, careful translation and cross-cultural adaptation are essential. This process is not merely about linguistic conversion; it involves ensuring the instrument retains its conceptual and content equivalence in the target language and cultural setting. For complex constructs like the built environment, and indeed for healthcare assessments in general, a robust adaptation process is as critical as the original instrument’s development.

While guidelines for instrument translation exist, such as those from the Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research for Patient-Reported Outcomes, a universally accepted gold standard for environmental assessments in nursing and high care settings is still evolving. Prior research highlights the varying degrees of adaptation processes, from simple forward translation to comprehensive back-translation with monolingual and bilingual testing, all aimed at achieving congruence between the original and adapted versions. The importance of meticulous planning and methodological rigor in ensuring validity and reliability in translated instruments cannot be overstated.

This article delves into the adaptation process of a specific environmental assessment tool – the Environmental Assessment Tool—High Care (EAT-HC) – across different cultural contexts. By comparing the adaptation methodologies employed in Germany, Japan, and Singapore, we aim to provide valuable insights and recommendations for adapting such tools in diverse settings. Our focus is on understanding the overarching needs and best practices for ensuring that environmental audit tools are not only linguistically accurate but also culturally sensitive and practically applicable in various high care environments worldwide. This exploration is particularly relevant for professionals in long-term care, environmental design, and healthcare policy seeking to leverage environmental assessments to improve the quality of care.

The Critical Role of the Built Environment in Dementia Care

The built environment has emerged as a critical factor in the provision of dementia-specific long-term care. Originating from specialized care environments in Australia in the late 1980s, the field has gained significant momentum in healthcare research and residential long-term care since the 1990s. However, the foundational understanding of the environment’s impact dates back to the 1970s, with Lawton’s ecology and aging theory. This theory emphasizes the dynamic interaction between individuals and their environment, positing that as capabilities decline, the need for a supportive environment, encompassing both social and built aspects, increases.

For individuals living with dementia, this environmental sensitivity is heightened. A well-designed built environment, attuned to their cognitive and sensory needs, becomes paramount. This begins with fundamental design elements like smaller living unit sizes and clear, navigable layouts, such as straight or circular hallways, which minimize confusion and maximize ease of movement.

Beyond basic spatial configurations, the incorporation of biographic elements and the creation of a familiar, home-like atmosphere within care facilities and their outdoor spaces are crucial. These principles align with dementia-specific design best practices, fostering a sense of comfort and reducing disorientation. These design considerations represent just a fraction of the extensive knowledge base concerning dementia-supportive built environments in residential long-term care. Over recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on disseminating this knowledge through guidelines for planners and designers, as well as assessment tools for healthcare professionals, bridging the gap between research and practical application.

Introducing the Environmental Assessment Tool—High Care (EAT-HC)

The Environmental Assessment Tool—High Care (EAT-HC) is a specialized instrument designed to evaluate the built environment for residents with moderate to severe cognitive and physical impairments. Developed by Fleming and Bennett, building upon their initial Environmental Assessment Tool, the EAT-HC is grounded in a comprehensive literature review and the extensive practical experience of its creators.

At its core, the EAT-HC is structured around 10 key design principles, which encapsulate best practices for creating supportive environments in high care settings:

- Unobtrusively Reduce Risks: Designing spaces to minimize potential hazards without being overly restrictive.

- Provide a Human Scale: Creating environments that feel comfortable and manageable, avoiding overwhelming or institutional scales.

- Allow People to See and Be Seen: Ensuring visibility and social connection within the environment, promoting interaction and reducing isolation.

- Manage Levels of Stimulation: Balancing sensory input to prevent both under-stimulation and over-stimulation, catering to varying needs.

- Support Movement and Engagement: Facilitating mobility and encouraging active participation through environmental design.

- Create a Familiar Place: Incorporating elements that foster a sense of homeliness and personal connection.

- Provide a Variety of Places to Be Alone or With Others: Offering diverse spaces that cater to both social interaction and the need for privacy and solitude.

- Design in Response to Vision for a Way of Life: Aligning the environment with the values and preferences of the residents, promoting person-centered care.

The original Australian version of the EAT-HC comprises 77 items, intended for use by researchers and multidisciplinary teams in nursing homes. Its psychometric properties have been rigorously tested, demonstrating satisfactory validity and reliability. Concurrent validity was established through correlations with similar instruments, and internal consistency within subscales has been shown to be robust. The EAT-HC stands as a valuable tool for systematically assessing and improving the quality of built environments in high care settings.

The Rationale for Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the EAT-HC

The impetus to translate and adapt the EAT-HC for use in Germany, Japan, and Singapore arose from a shared need to enhance the quality of long-term care environments for individuals with dementia in these diverse cultural settings. While Australia, Germany, Japan, and Singapore share the challenge of aging populations and increasing dementia prevalence, their specific contexts of long-term care provision, cultural norms, and built environment characteristics differ significantly.

For instance, population density varies dramatically, from sparsely populated Australia to densely populated Singapore. Funding models for long-term care also differ, with Germany and Japan having robust public long-term care insurance systems. These demographic and economic factors shape the landscape of long-term care facilities and the specific needs within each country.

Germany

Germany, with a rapidly aging population and a growing number of people living with dementia, faces the challenge of providing adequate care in diverse living arrangements. While specialized dementia care units exist, the majority of residents with dementia are integrated into general nursing home units. A significant gap existed in Germany: the absence of a validated tool to assess the built environment’s suitability for people with dementia across these varied care settings. Adapting the EAT-HC was seen as crucial for both research and practice. For researchers, it offered a means to integrate the built environment as a contextual variable in evaluating complex care interventions. For practitioners, it provided a systematic framework for assessing and improving their living units, aligning with German legal requirements for dementia care.

Japan

Japan, with the world’s oldest population, is rapidly transitioning towards small-scale, homelike living facilities for the elderly. While the Physical Environment Assessment Protocol (PEAP) Japan Version 3 existed, its usability in these smaller settings was limited. The PEAP required specialized skills and was not designed for smaller facilities or residents with limited mobility, who constitute a significant portion of residents in Japanese small-scale living units. The EAT-HC, with its ease of use for care staff, focus on smaller scale homes, and relevance to residents with advanced dementia, was identified as an ideal instrument for adaptation in the Japanese context, aiming to enhance the quality of life for residents in these evolving care environments.

Singapore

Singapore, despite its relatively smaller aging population compared to Germany and Japan, faces a growing dementia prevalence and a limited number of nursing home beds. Existing nursing home designs in Singapore were described as often pathogenic and restrictive, highlighting a need for more dementia-enabling environments. While national guidelines for dementia-friendly nursing home design were introduced, a culturally sensitive and validated tool to evaluate these environments was lacking. A scoping review suggested the EAT-HC’s potential for adaptation to the Singaporean context. This led to the development of the Singapore Environmental Assessment Tool (SEAT), a validated and culturally adapted version of the EAT-HC, specifically tailored to the needs and context of long-term care in Singapore.

Aims of the Adaptation Study

This study is driven by two primary aims:

- To comprehensively analyze and discuss the experiences encountered during the translation, linguistic validation, and cross-cultural adaptation of the EAT-HC in Germany, Japan, and Singapore.

- To pinpoint the overarching needs and essential considerations for adapting the EAT-HC, and similar environmental audit tools, for effective use in diverse cultural and linguistic settings globally.

Methodology: A Thematic Analysis Approach

To systematically compare the adaptation processes of the EAT-HC across Germany, Japan, and Singapore, a thematic analysis approach was employed. This methodology facilitates the structured discussion of diverse methods, acting as a bridge between qualitative and quantitative approaches, and is particularly suited for comparing rarely documented processes like EAT-HC adaptations.

The process began with the collection of all available data related to the three adaptation projects. This included interview transcripts, detailed documentation of the adaptation steps undertaken, and written notes from researcher group discussions. While interview transcripts from Germany and Japan were in their respective target languages, the core information was verbally conveyed and documented in English for analysis.

The initial coding of the data was deductive, guided by the distinct steps of the adaptation process. This structured coding allowed for the identification of both overarching similarities and culture-specific variations in the adaptation approaches. Subsequently, the research teams from Germany, Japan, and Singapore collaboratively reviewed and discussed the coded results to identify key themes emerging from the data. These themes, such as language-related challenges and cultural nuances, were then critically evaluated in relation to the solutions developed during each adaptation process. From this in-depth analysis, practical recommendations for future adaptations of the EAT-HC were derived. The qualitative data analysis was facilitated using MAXQDA 2020 software.

Ethical Considerations

This research, being a comparative analysis of existing adaptation processes and not involving new empirical data collection, did not necessitate new ethical committee approvals. Ethical clearances were secured for the original EAT-HC adaptation projects in each country, adhering to the ethical guidelines of Germany, Japan, and Singapore.

Results: Key Findings from Cross-Cultural Adaptations

The comparative analysis of the EAT-HC adaptation processes in Germany, Japan, and Singapore revealed overarching experiences and practical insights across several key areas.

Instrument Adaptation Processes: Adhering to Guidelines with Flexibility

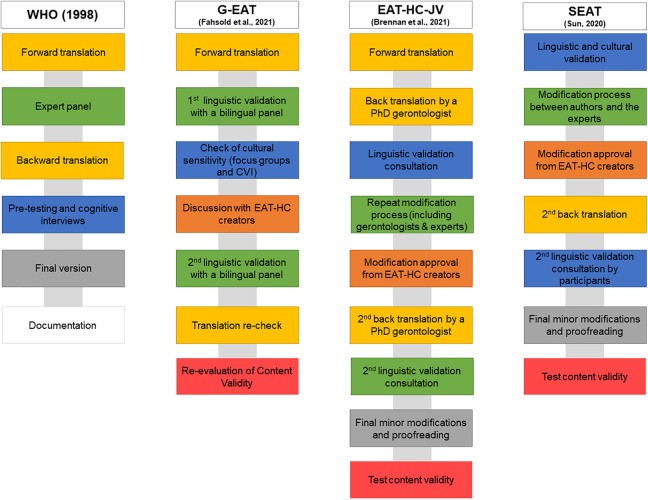

The adaptation of each EAT-HC version was grounded in the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines from 1998, a multi-stage process emphasizing the involvement of potential users in the target language. These guidelines were chosen for their robust research base and global applicability. While the WHO guidelines served as a foundational framework, each research team tailored the process to suit their specific national context and language requirements.

Figure 1. Adapted World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines for Environmental Audit Tool High Care (EAT-HC) Translation Processes

To ensure the tool’s practical relevance and usability, environmental design experts and experienced long-term care practitioners were actively engaged throughout the adaptation process. These stakeholders represented the primary user groups of the EAT-HC: planning experts, researchers, and healthcare practitioners. The six steps of the WHO guidelines were further细化 and modified to provide greater specificity, and two additional steps were incorporated: consultation with the EAT-HC creators and empirical evaluation of content validity. Consultation with the EAT-HC developers was crucial to assess the tool’s applicability in the target countries, considering geographical and social contexts, and to clarify any ambiguities in the EAT-HC’s content and theoretical underpinnings. Content validity was evaluated as a prerequisite for establishing reliability. The detailed findings of the instrument versions’ test results are reported separately. The overarching goals guiding all adaptation steps were translation, linguistic validation, and cross-cultural adaptation, ensuring the integrity and relevance of the EAT-HC in each new context.

Translation into Target Languages: Balancing Linguistic Accuracy and Cultural Nuance

The German and Japanese teams initiated the process with forward translation, utilizing experts in gerontology, environmental design, and nursing, rather than solely relying on professional translators. The Japanese translation included an initial step of adapting Australian-English terms to American-English equivalents before translation to Japanese, enhancing clarity for the Japanese context. Both the German and Japanese versions prioritized politeness and respect, reflecting cultural norms, and aimed for plain language while preserving the core concepts of the EAT-HC. It was recognized that some environmental terms were unfamiliar to potential users, such as long-term care facility administrators, highlighting the need for clear and accessible language. Notably, the Singaporean adaptation did not require forward translation as English is a national language, simplifying the initial linguistic conversion phase.

Linguistic Validation: Expert Review and User Feedback

All adapted versions underwent rigorous linguistic validation, involving experts from various relevant fields within each country. These experts were native speakers residing in the target countries, aligning with best practices for instrument adaptation. The expert panels included architects and residential environment planners in Japan and Singapore, broadening the perspectives beyond healthcare professionals. In Germany, nursing scientists were involved to ensure the tool’s relevance for a diverse range of potential users. Participant recruitment leveraged the professional networks of each research team. While Japan employed individual expert consultations, Singapore utilized focus group interviews with a large number of experts, and Germany combined a bilingual panel with focus groups. Singapore’s validation process emphasized readability and usability, while Germany focused on the comprehension of item content, reflecting the specific priorities in each context.

Overarching Needs for Cross-Cultural Adaptation: Navigating Cultural and Contextual Differences

The cross-cultural adaptations highlighted several overarching needs stemming from cultural, linguistic, and contextual differences.

Challenges with “Hard-to-Adapt” Items: Visual Access and Contrast

Certain EAT-HC items proved particularly challenging to adapt across cultures. For example, the item concerning “visual access to commonly used spaces” (Items 3.1–3.3) raised concerns in Japan about the viewpoint dependency of the assessment. In Singapore, practitioners questioned the definition of “appropriate” visual access, while German experts noted that visual access might be counterproductive for some residents, potentially inducing agitation. The concept of “contrast” also presented challenges, particularly in items like “Do the toilet seats contrast with the background?” (Item 5.9). Interpretations of “contrast” varied, with Japanese users focusing on color difference rather than subtle contrast issues, Singaporean experts questioning the threshold for “contrast,” and German experts debating the degree of contrast required for identification.

Divergent Understandings of Key Design Principles: Familiarity

The key design principle of “create a familiar place” was interpreted differently across contexts. In Japan, where fully furnished facilities are common, familiarity was seen as highly individual and less dependent on built environment features. Singaporean participants emphasized the need for nursing home environments to mirror the design of common public housing flats, contrasting with the prevailing hospital-like designs. This hospital-like environment was perceived as reinforcing a short-term, clinical care model, rather than a homelike, psychosocially supportive setting. German experts highlighted the person-centered nature of “familiarity,” arguing against a universal assessment across residents within a living unit.

Variations in Long-Term Care Contexts: Geographical and Structural Differences

Beyond instrument-specific adaptations, broader contextual variations in long-term care settings emerged. Geographical differences impacted the applicability of certain items, particularly those related to outdoor spaces. In Japan and Singapore, where multistory nursing homes and vertical public housing are prevalent, direct, level access to outside areas is not always the norm. Elevators become critical for independent access to outdoor spaces, a factor less emphasized in the Australian context. Furthermore, the need for training for long-term care practitioners in all three settings to enhance their understanding of the EAT-HC’s key design principles was evident. Misinterpretations of item goals, such as items 3.6/3.7 regarding toilet visibility from communal areas, highlighted the importance of clarifying the underlying intent of design features – in this case, balancing visual access with resident independence, rather than simply maximizing visibility.

Linguistic Particularities: Australian-English Terminology

Adaptations also addressed specific Australian-English terms that lacked direct equivalents or common usage in the target languages. Synonyms were identified, or terms were omitted when culturally irrelevant. Consultation with the EAT-HC creators ensured that terminological modifications preserved the original item meaning.

Table 1. Overlapping Wording Modification in the EAT-HC Adapted Versions Due to Cultural Differences

| Item | Original Version | Modification in | Modification Into | Reasons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | Can people who live in the unit be prevented from leaving the garden/outside area by getting over or under the perimeter? | G-EAT, EAT-HC-JV | Omitted “under” | No ranch style fence in Germany and Japan |

| 5.16 | Outside, are a variety of materials and finishes used to create an interesting and varied environment for a person with dementia and help them know where they are (e.g. brick, timber stone, grass)? | G-EAT, EAT-HC-JV | Wood | Not common |

| 8.3 | How many different characters are there within the unit (e.g., cosy lounge, TV room, sunroom)? | G-EAT, EAT-HC-JV, SEAT | Omitted “sunroom” | No sunrooms in Singapore, Germany, and Japan |

| Several items | Lounge room | EAT-HC-JV, SEAT | Living room | Not a common term |

Instrument Features in Target Countries: Evolution and Customization

The adaptation processes resulted in three distinct versions of the EAT-HC, each reflecting the specific needs and context of the target country.

Table 2. Instruments’ Features in the Target Countries

| Feature | G-EAT | EAT-HC-JV | SEAT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of items | (74) a 77 | 77 | 81 |

| Deleted items | (3) a 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New items | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Subscales | Same as original EAT-HC | Same as original EAT-HC | Same as original EAT-HC |

| Additional material provided | Handbook planned, but not published yet | none | User guide |

The Japanese version (EAT-HC-JV) remained a direct translation, closely mirroring the original instrument. In contrast, the German Environmental Audit Tool (G-EAT) and the Singapore Environmental Assessment Tool (SEAT) incorporated more substantial national contextual adaptations. While all three retained the core 77 items of the EAT-HC, reflecting a commitment to comprehensiveness, SEAT expanded to 81 items, adding new items related to palliative care, spirituality, and technology, areas of particular relevance in the Singaporean context. G-EAT, for non-secure living units, excluded three items from the “Unobtrusively reduce risks” principle, deemed legally inapplicable in that setting. Feedback from experts across all three countries highlighted the need for supplementary materials to facilitate instrument use by diverse user groups. Consequently, a user guide, based on the original EAT-HC handbook, was developed for SEAT, and similar guides are planned for G-EAT and EAT-HC-JV, enhancing accessibility and usability.

Discussion: Enhancing Environmental Audit Tools for Global Application

The comparative analysis of EAT-HC adaptation processes across three diverse countries underscores the importance of rigorous cross-cultural adaptation for environmental audit tools in high care settings. The experiences and insights gained provide valuable guidance for future adaptations, aiming to enhance the global applicability and effectiveness of such tools.

Benefits of Adhering to Translation Guidelines: Ensuring Quality and Comparability

The consistent use of the WHO guidelines by all three research teams, while allowing for necessary adaptations, proved beneficial. This structured approach facilitated the engagement of diverse user groups, ensuring both semantic equivalence through expert review and practical relevance through healthcare practitioner feedback. As highlighted by other researchers, involving a wide range of users, including healthcare aids who provide a significant portion of direct care, is crucial for ensuring the validity and applicability of adapted instruments across all user levels.

Adhering to established guidelines like the WHO’s also promotes the comparability of adapted instrument versions. When adaptations follow a common methodological framework, the resulting tools are more likely to maintain conceptual equivalence, even with linguistic and cultural adjustments. This is particularly important for complex constructs like the built environment, where interpretations can vary widely. The consistent application of adaptation guidelines strengthens the rigor and validity of cross-cultural research using environmental audit tools.

Contextual Awareness: Recognizing Origin and Target Country Factors

As emphasized by researchers in cross-cultural research, adapting instruments necessitates not only linguistic translation but also careful consideration of the original and target contexts. The EAT-HC adaptations highlighted significant differences in dementia-specific and residential long-term care approaches across countries. For instance, Japan prioritizes small-scale, homelike facilities focused on privacy and dignity, while Singapore’s long-term care design has historically emphasized protective environments, prioritizing longevity. These differing cultural perspectives and contextual factors directly influence the interpretation and relevance of environmental assessment items, underscoring the need for culturally sensitive adaptation.

Collaboration with Instrument Creators: Mitigating Incongruence and Enhancing Validity

To address potential incongruence arising from cultural and contextual differences, consultation with the EAT-HC developers proved invaluable. Clarification of Australian-English phrases and in-depth discussions about challenging items and the underlying design principles ensured accurate interpretation and adaptation. This collaborative approach aligns with recommendations from other researchers, emphasizing the importance of intercultural exchange and developer involvement in translation processes. Such collaboration is crucial for maintaining the conceptual integrity of the instrument and enhancing its validity in new cultural contexts. Increased transparency in reporting collaboration processes during instrument adaptation is essential for advancing understanding of instrument validity and cross-cultural research methodology.

Conclusion: Towards Enhanced Global Application of Environmental Audit Tools

This comparative analysis of EAT-HC adaptations in Germany, Japan, and Singapore provides valuable insights into the complexities and best practices of cross-cultural instrument adaptation. The identified overarching needs related to linguistic and cultural differences offer practical guidance for researchers and practitioners seeking to adapt environmental audit tools for high care settings in diverse global contexts.

The findings underscore the benefits of:

- Utilizing established guidelines, such as the WHO guidelines, as a framework for adaptation, ensuring a structured and rigorous process.

- Engaging diverse user groups, including experts, practitioners, and care staff, throughout the adaptation process to enhance relevance and usability.

- Prioritizing cultural sensitivity and contextual awareness, recognizing the influence of cultural norms and long-term care systems on instrument interpretation and application.

- Collaborating with instrument developers to clarify ambiguities, ensure conceptual equivalence, and enhance the validity of adapted versions.

The experiences shared in this article serve as a valuable resource for researchers adapting complex instruments, particularly in the field of environmental assessment for high care settings. The cross-cultural comparison highlights broader considerations regarding environmental design approaches and dementia-design literacy among long-term care professionals across different countries, areas ripe for further collaborative exploration and knowledge exchange.

Implications for Practice

- This article offers a critical analysis of the EAT-HC adaptation process across three countries, identifying both commonalities and unique challenges. This comparative perspective is invaluable for researchers planning to adapt the EAT-HC or similar environmental audit tools for use in new cultural contexts.

- Involving potential users in the instrument translation and adaptation process, while potentially increasing complexity and time investment, is crucial. It effectively identifies linguistic and conceptual barriers and facilitators, ensuring the adapted instrument is relevant and user-friendly in the target setting.

- While a definitive gold standard for environmental assessment translation remains elusive, critically evaluating and leveraging existing guidelines is highly beneficial. This approach enhances the transparency and rigor of the adaptation process, incorporating established validation methodologies and strengthening the credibility of the adapted instrument.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Kirsty Bennett and Richard Fleming, the developers of the EAT-HC, for their unwavering support throughout the cross-cultural adaptation process. We also acknowledge the invaluable contributions of all experts, practitioners, and institutions involved in the adaptation projects in Germany, Japan, and Singapore.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: AF, SB, TD, and SJ conceptualized and drafted this article. AF, RP, BH, SB, TD, and SJ were involved in planning, conducting, and analyzing the original studies in each country. AF conducted the cross-cultural analyses for this article. RP, BH, and HV revised the article critically. All authors approved the version to be published.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iDs: Anne Fahsold, RN, BSc, MSc https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7977-8805

Therese Doan, RN, PhD https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3207-5619

Joanna Sun, MCouns, BSc Psych, EN, PhD https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5190-7137