A month ago, I became the subject of my own cybersecurity nightmare: my car was hacked and stolen from my driveway in the dead of night. As a cybersecurity journalist with 18 years of experience covering car hacking, I had always felt somewhat detached from the reality of cyber threats, falling into the trap of believing “it won’t happen to me.” This experience shattered that illusion and provided a stark reminder that even seasoned professionals can become victims.

Let me be upfront about mentioning the make of my car, a Mercedes-Benz GLC 220 AMG Line Premium D. It’s not about being ostentatious; it’s crucial to understanding how it was stolen. Mercedes even contributed to this article, highlighting the relevance of the brand. And for the record, this was the nicest car I’d ever owned – hardly a luxury vehicle in the grand scheme of things!

Over my career, I’ve written extensively about car hacking, even interviewing cybersecurity luminary Charlie Miller. Yet, like many, I underestimated the personal risk. Now, I find myself among the hundreds of thousands in the UK who experience car theft annually. My only advantage? A network of cybersecurity experts ready to dissect my experience and offer crucial insights.

The Stark Reality of Car Theft: Numbers Don’t Lie

The latest figures from the DVLA are alarming: a car is stolen in the UK roughly every eight minutes. Analysis from the Office of National Statistics reveals a staggering 397,264 cars were stolen in England and Wales between October 2022 and September 2023. This figure, often understated in media reports, was confirmed directly with the ONS.

Luxury brands are particularly targeted. Land Rover tops the list of most stolen cars, with Mercedes taking second place and Ford third – unwanted accolades for any manufacturer. Recovery rates are dismal, with most sources estimating less than 20% of stolen vehicles are ever recovered.

But how are these vehicles vanishing without a trace of forced entry, silently disappearing from driveways overnight? The answer, in many cases, is that hackers are using cars as tools.

Was My Car Hacked? A Cybersecurity Journalist’s Perspective

My Mercedes GLC 220, equipped with keyless entry and start, became a target. The detective on my case revealed a chilling detail: six similar high-value cars were stolen within a mile radius over just two nights. Law enforcement suspects an organized crime group traveled from major cities like London or Birmingham to Oxfordshire to carry out these thefts.

Waking up to an empty driveway on a rainy February morning was surreal. Both car keys were exactly where we always kept them inside the house. My partner hadn’t moved the car, and there was no broken glass, no sign of forced entry on our secluded driveway. The inescapable conclusion: my car was likely hacked.

“I’d say so, yes,” confirmed Graham Cluley, host of the Smashing Security podcast. “In its broadest sense, hacking is gaining unauthorized access to something. The criminals who stole your car did just that, by exploiting a vulnerability in its entry system.”

David Rogers, CEO of Copper Horse, a connected car security specialist, concurred: “It’s almost certainly car hacking.” The consensus among experts was clear.

However, Adam Pilton, a former police officer and now senior cybersecurity consultant at CyberSmart, offered a nuanced perspective. “While ‘car hacking’ might evoke images of complex cyberattacks, the theft of six cars in a short period suggests a simpler method: a relay attack. This is a far more effective and less sophisticated technique.” This raises the crucial question: is a relay attack a form of hacking?

Ivan Reedman, director of secure engineering at IOActive, provided a reality check based on the technical definition of hacking: “If we define hacking as gaining unauthorized access to data in a system, then technically, this might be classified as theft rather than a hack. The criminals gained access to the car, but not necessarily to its data.”

Relay Attacks: The Go-To Tool for Car Thieves

Despite varying definitions, the cybersecurity experts I consulted unanimously pointed to a relay attack as the method used to steal my car. My Mercedes had ‘passive entry passive start’ (PEPS), meaning I could unlock and start the car as long as the key was nearby, without pressing buttons or even touching the key.

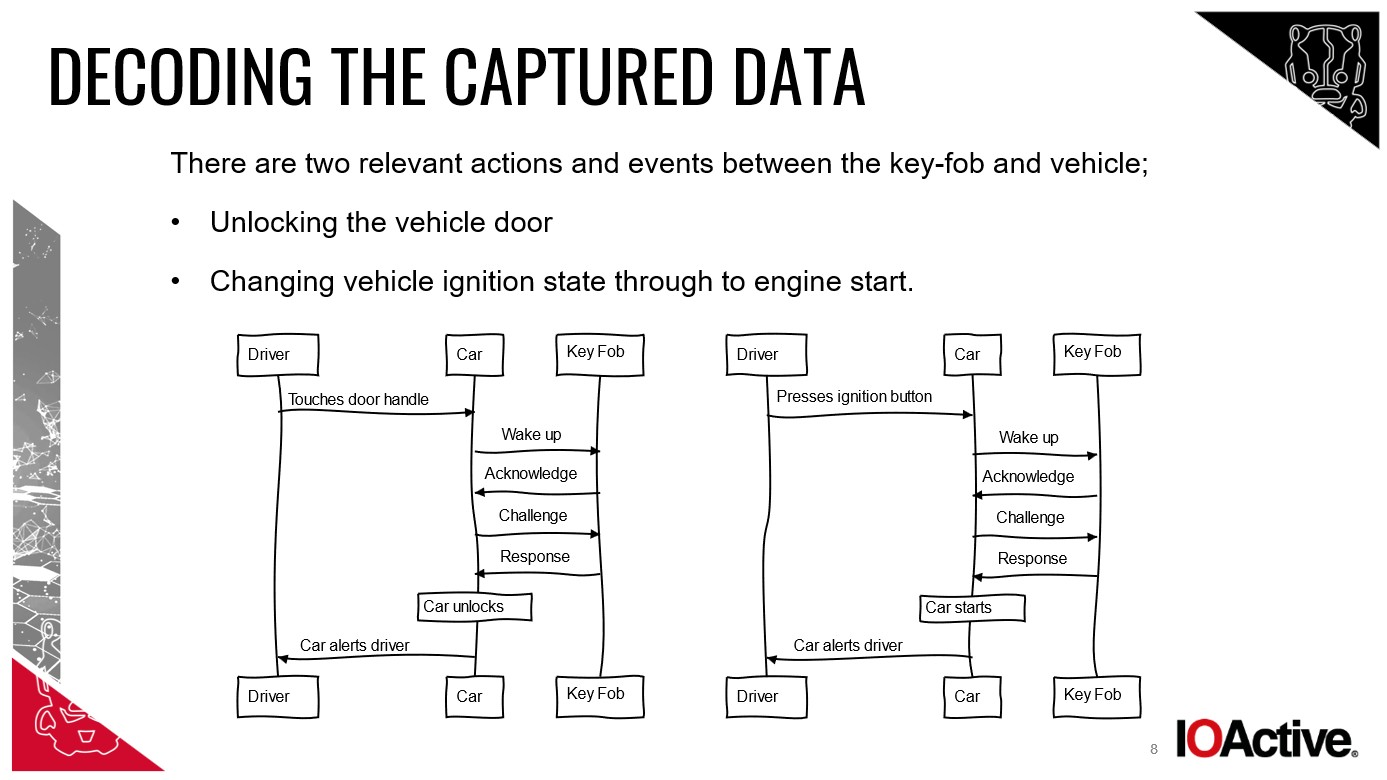

Decoding the Communication: How key fobs, cars, and drivers interact in normal keyless entry scenarios.

Chris Pritchard, principal adversarial engineer at Lares, explained the mechanics: “Thieves use a tool and antenna to relay the signal between your key fob and the car. The car is tricked into thinking the key is in proximity and unlocks.”

William Wright, CEO at Closed Door Security, elaborated: “The attack requires two devices. One is placed near your house to capture the key fob’s signal, even through walls. The other device, positioned near the car, relays that signal, effectively extending the key’s range.”

Relay devices only need to be within 10-15 meters of the key to work and can execute the theft in as little as 30 seconds.

Reedman clarified the process: “The device near the key relays the fob’s signal directly to the car, allowing thieves to enter and drive away instantly. It’s a range extension attack, exploiting the PEPS functionality.”

He famously demonstrated this on BBC’s One Show using readily available components like an audio amplifier, AA batteries, and copper wire, unlocking and driving off in a Mercedes AMG belonging to a producer.

Once inside and driving, how do thieves keep the car going when the key signal is no longer present? “Once the engine is started, most vehicles will warn that the key is absent but won’t shut off the engine,” Reedman explained. “The engine will run until stopped. Afterward, the thieves can use other tools to assign a new key and disable your original keys.”

Cluley added: “The car won’t stop mid-drive if it loses key signal – that would be dangerous if the key battery died, for example. However, restarting the car after stopping is usually prevented.”

OBD Hacking: The Next Step in Car Theft

Relay attacks get thieves into the car and driving, but only until the engine is turned off. To gain full control, they need to access the on-board diagnostics (OBD) port. “OBD access allows them to bypass security and start the car using programming devices,” Rogers stated.

Pritchard described the OBD port’s location: “It’s typically under the steering wheel, to the right. Mechanics use it for diagnostics and resetting warning lights.” He shared his own experience: “When my Audi was stolen for use in an armed robbery, they broke in and used an OBD tool to program a new key, enabling them to operate the car fully. Something similar likely happened in your case.”

Experts dismissed the idea of key cloning as too complex in this scenario.

Flipper Zero: Unlikely Culprit in Sophisticated Car Theft

Initially, after I shared my experience on X (formerly Twitter), some experts suggested a Flipper Zero attack might be involved. The Flipper Zero, a versatile handheld device, can test wireless networks, clone access cards, and transmit infrared and radio signals. The Canadian government even banned it, claiming it was instrumental in rising auto theft.

The Flipper Zero device has been controversially linked to a rise in vehicle thefts, though experts dispute its role in sophisticated attacks like relay theft.

However, after reviewing the details of my case, the experts I interviewed deemed Flipper Zero involvement “highly improbable,” in Reedman’s words. Pritchard emphasized, “Despite the Canadian government’s claims, this isn’t a Flipper attack. While powerful, it’s not designed for sophisticated relay attacks.”

Who Are the Hackers Using Cars as Tools?

Having understood how my car was stolen, the question shifted to who was behind it and how they acquired the skills and tools.

“The relay attack technique is well-known among car thieves, and instructions are readily available online,” Cluley explained.

Rogers highlighted the accessibility of car theft equipment: “Car theft tools are surprisingly easy to obtain. Most car thieves lack deep technical knowledge; they simply operate pre-programmed devices.” The real expertise, he noted, lies higher up the criminal chain – in the R&D and supply of these tools, often linked to other criminal activities like ATM skimming.

Pilton added, “The tools themselves aren’t solely designed for car theft. They are often repurposed communication and signal extension devices. Like a crowbar, criminals adapt them. The individuals carrying out the theft might just be using pre-configured tools handed to them by a larger operation.”

Reedman argues this is why he hesitates to call it “car hacking.” “It requires minimal skill. They likely watch online tutorials and buy relay equipment. It’s trivial. Hacking, in my view, implies a higher level of skill.”

Alarmingly, reports indicate children as young as 10 have been arrested for car theft, and 12-year-olds charged. Direct Line Motor Insurance reported over 1,000 children charged with vehicle theft in three years, reinforcing the ease of executing relay attacks. “They probably learned to drive in Mario Kart and GTA V,” Cluley quipped.

Automakers’ Response: A Very Mercedes Perspective

With car theft surging and keyless entry cars being prime targets, manufacturers face increasing pressure to act. However, Wright believes “the automotive industry lags behind others in cybersecurity protection.”

Mercedes-Benz, when contacted for this article, emphasized their commitment to security. A spokesperson stated, “The security of our organization, products, and services is a top priority in our R&D.”

Mercedes-Benz introduced motion sensor technology in key fobs from mid-2019 onwards, a feature my 2018 GLC model lacked.

The spokesperson explained that from mid-2019, the GLC “facelift” version incorporated a motion sensor in the key fob. “If the key remains still for a period, the KEYLESS GO function deactivates, preventing range extension attacks.” My 2018 model predated this upgrade.

Mercedes also highlighted the option to manually disable KEYLESS GO and the GUARD 360° ‘stolen vehicle help’ service, allowing users to report theft via the Mercedes me app and initiate vehicle tracking with law enforcement. However, they didn’t comment on why disabling KEYLESS GO isn’t promoted more actively to customers at purchase.

Shifting the Blame? “It’s Not Us, It’s You”

“Car manufacturers prioritize convenience over security,” Pritchard argued. “Range Rover thefts have become so rampant that JLR now offers its own insurance due to unaffordable premiums from standard insurers.”

Rogers believes automakers misunderstand the criminal ecosystem and lack urgency in addressing new theft techniques. “Solutions exist for rapid deployment, but there’s a reluctance to acknowledge the problem.”

He criticized the tendency to blame victims: “Owners are told to keep keys away from ground floors or block keyless cars with non-keyless vehicles. This is misplaced blame. Manufacturers are aware of these vulnerabilities but often fail to act decisively. However, manufacturers are also victims. International law enforcement needs to target the international organized crime groups supplying these tools.”

Some manufacturers are implementing motion sensors in key fobs, putting them into ‘sleep mode’ when stationary. Others use positioning technology to verify key proximity more accurately.

Pilton advocates for shared responsibility, urging collaboration between manufacturers, software developers, and regulators to establish minimum security standards and empower informed consumer choices. Making car owners aware of keyless entry risks at the point of sale is a crucial step.

Cluley summarized the manufacturer’s likely perspective: “Car manufacturers have known these risks for years, but implementing changes is time-consuming and costly.”

The Criminal Justice Bill: A Double-Edged Sword?

The UK’s Criminal Justice Bill, introduced in November 2023, aims to criminalize the possession of electronic devices used for vehicle theft. It targets “signal jammers used in vehicle theft” and strengthens Serious Crime Prevention Orders.

However, Rogers and the security research community express concern that this legislation could stifle security research, potentially leading to arrests for researchers using these technologies to identify and prevent theft. The Bill is still under review in the House of Lords, offering an opportunity for amendments.

The Appeal of “Dumb Cars”

Criminals target the easiest opportunities first. Relay attack car theft is appealing due to its simplicity, lack of forced entry, and minimal risk. “It’s a low-risk crime with no damage to the vehicle, maximizing resale value for criminals,” Pritchard noted.

Pilton emphasized the trade-off: “While traditional key-based systems have their weaknesses, keyless entry offers convenience at the cost of increased vulnerability to specific attack methods.”

Cluley admitted, “I’m very glad to have a ‘dumb car.'”

My social media post about the theft triggered a flood of similar stories, highlighting the scale of the problem. Recovery rates are low, and prosecutions are even rarer.

The Elusive Path to Prosecution

Wright lamented the “very poor” success rates for finding and prosecuting car thieves due to the ‘smash and grab’ nature of relay attacks. “They are gone before you notice, tracking disabled, plates changed, likely shipped abroad within a day.”

Rogers described efforts to intercept stolen cars in containers or dismantle operations in ‘chop shops,’ but stressed the need to target the tool suppliers to effectively curb the problem.

The era of smashed windows and forced entry is fading as sophisticated cyber methods become the tool of choice for car thieves.

Pilton recounted his law enforcement experience: “Investigating overnight disappearances is incredibly challenging. Identifying perpetrators can be extremely difficult, even impossible.” While law enforcement sometimes recovers vehicles, often burnt out or already exported, directly linking suspects to individual thefts is rare. Organized crime groups often leave “breadcrumbs” that allow law enforcement to build broader cases and target entire groups.

A month after my car was stolen, there’s no trace of it or the other five vehicles. The detective suspects my car might have been used for ram-raiding cash machines due to its size, but it could equally be overseas or dismantled in a chop shop. The investigation continues, including forensic analysis of recovered license plates and tracking data from cars with embedded SIMs. Recovery seems unlikely, but I still hope for answers and some measure of justice.

Securing Your Keyless Car: Practical Steps

My own experience has been a harsh lesson. Despite storing my key away from the front door, I was unaware of the relay attack threat. Now, my perspective has drastically changed. I asked the experts for their advice on protecting keyless cars. The unanimous recommendation? Faraday.

“Use a Faraday box or wallet to block signals from your car keys, making it a habit every time you come home,” Cluley advised. Store spare keys in Faraday protection too.

Reedman emphasized testing Faraday effectiveness: “Test if you can unlock your car with the key inside the Faraday box. If so, it’s not working properly.” He also cautioned that not all Faraday enclosures are equal, and a fully enclosed metal box stored away from the car is the most reliable solution.

Rogers suggested disabling keyless ignition if possible, using a mechanical steering lock, and considering an OBDII port lock to physically secure the diagnostic port.

Pilton stressed the importance of raising awareness through social media and sharing experiences to encourage preventative measures.

Dan Bulman, co-founder of KEYSHIELD, contacted me with a new security device: a KEYSHIELD sleeve that disables key fob battery power when stationary using motion sensor technology. While testing it on my new car, I encountered an issue where it seemed to prevent even legitimate key operation, triggering the alarm. Bulman is investigating this unexpected result.

Moving forward, I’m adopting a layered approach: Faraday box and a steering wheel lock. My cybersecurity cynicism, once complacent, is now fully reinstated and actively protecting my new vehicle.

This personal experience underscores the vulnerability of keyless cars and the ease with which hackers can use them as tools. Until automakers prioritize security alongside convenience and actively educate owners, articles like this are vital to empower car owners to take control of their vehicle security.